Club financial analysis: West Ham United FC 2023/24

Game State's analysis of West Ham United FC's 2023/24 financial results.

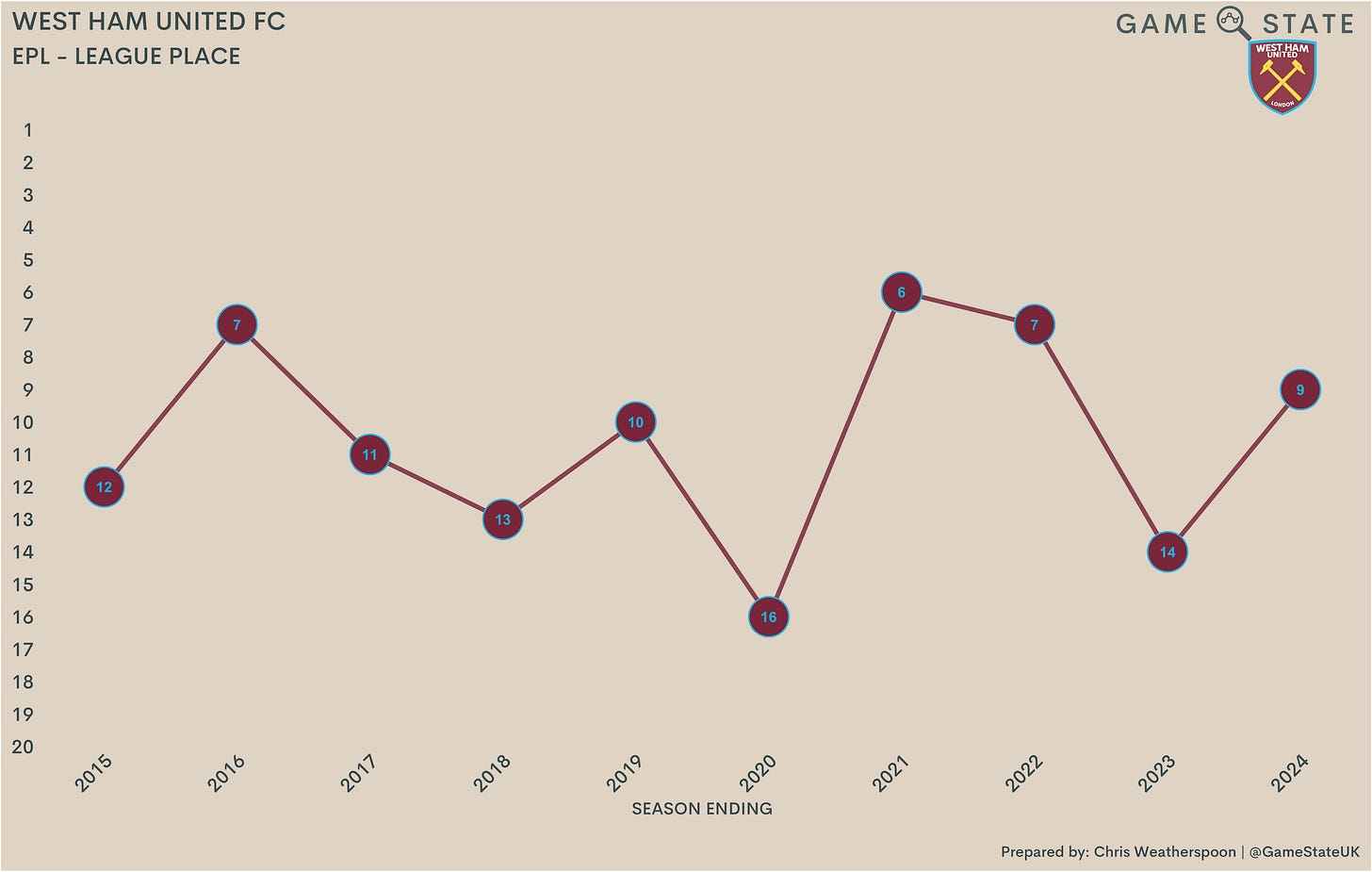

West Ham United’s 2023/24 season was never likely to reach the heights of a year earlier. That previous season had culminated in the club’s first trophy in 43 years, as they became the first English winners of the nascent European Conference League, defeating Fiorentina 2-1 in the final in Prague. That game also marked the perfect farewell for club captain Declan Rice, who left The Hammers for Arsenal a month later in a club record £100 million deal (potentially rising by a further £5 million if future conditions are met).

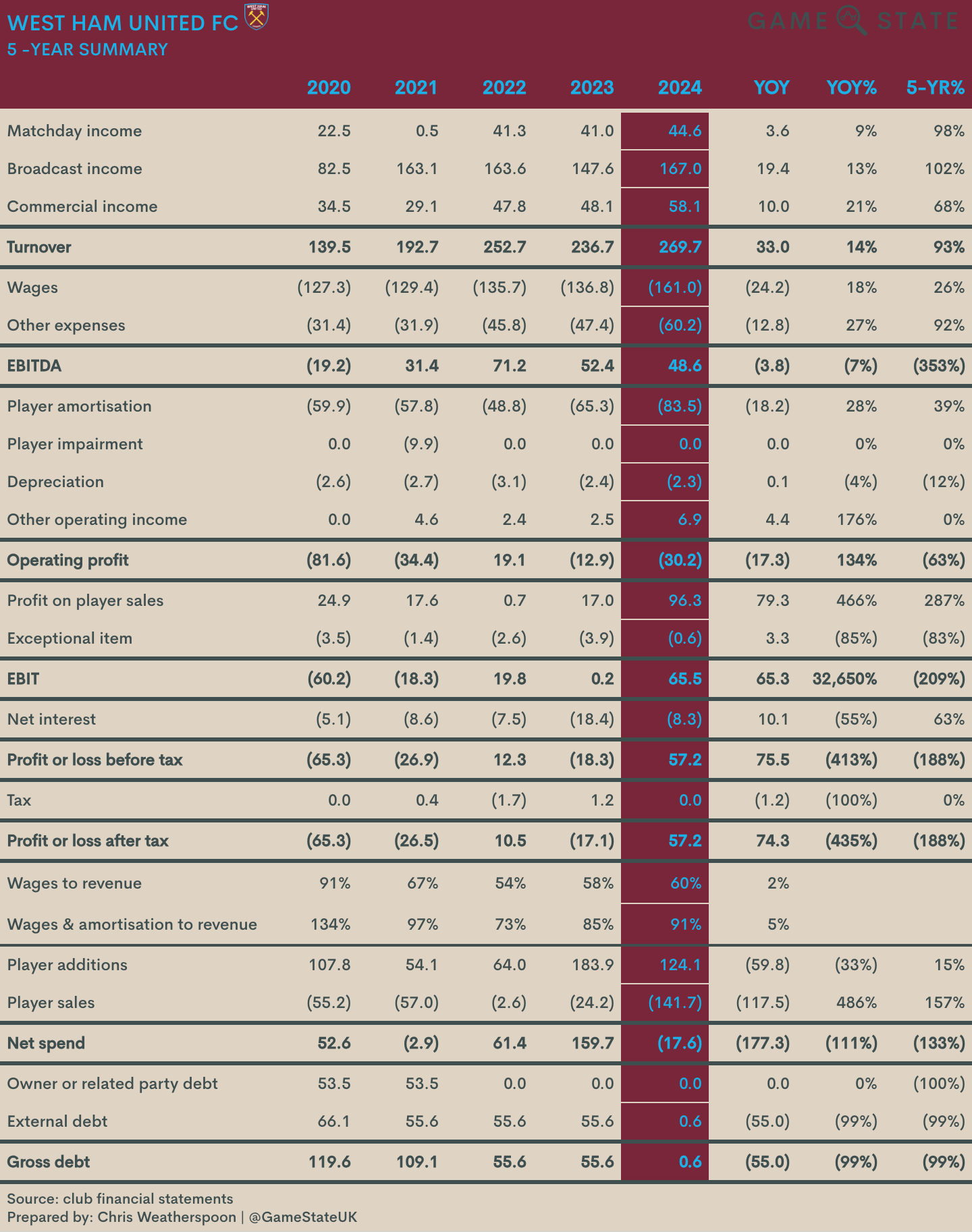

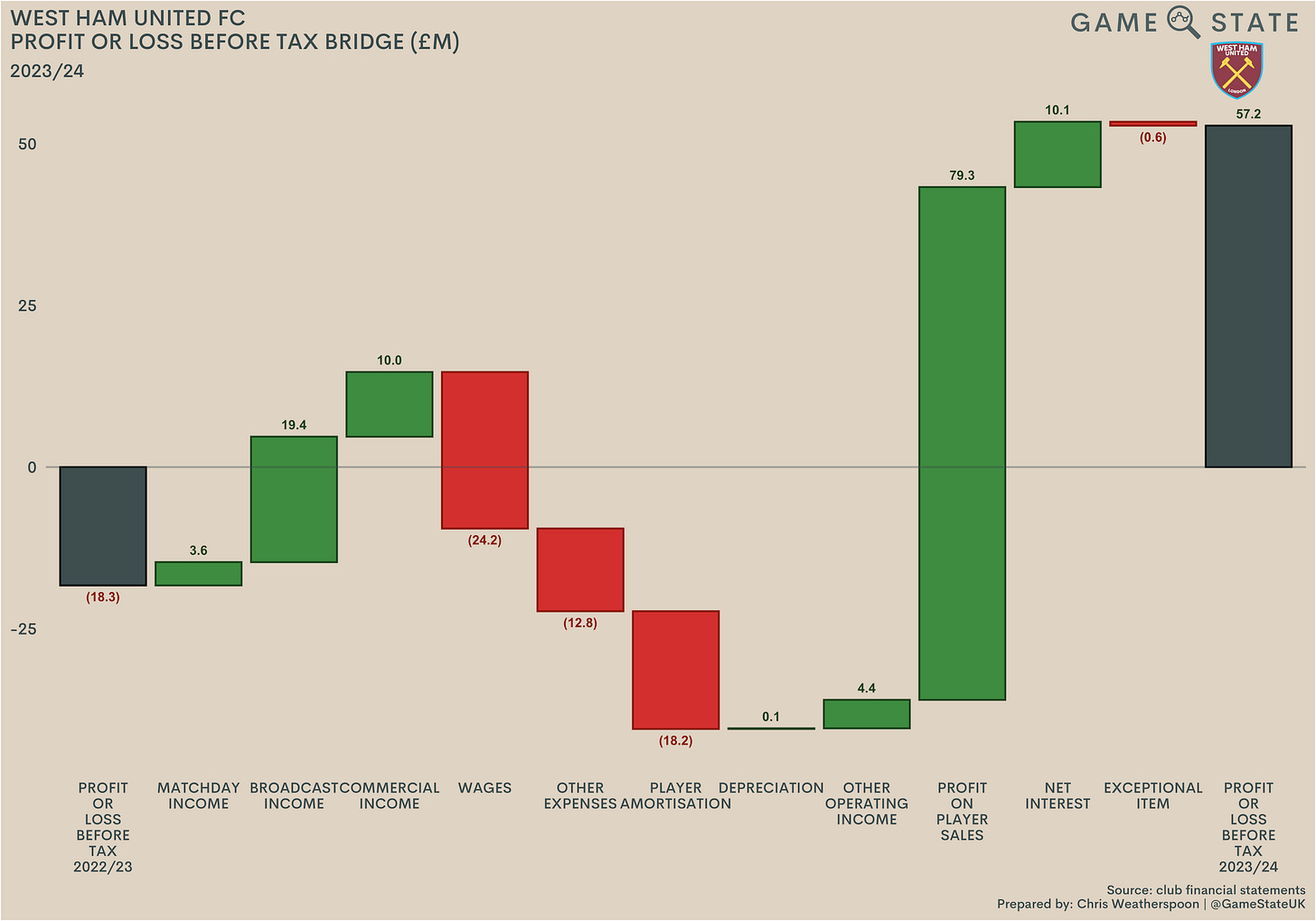

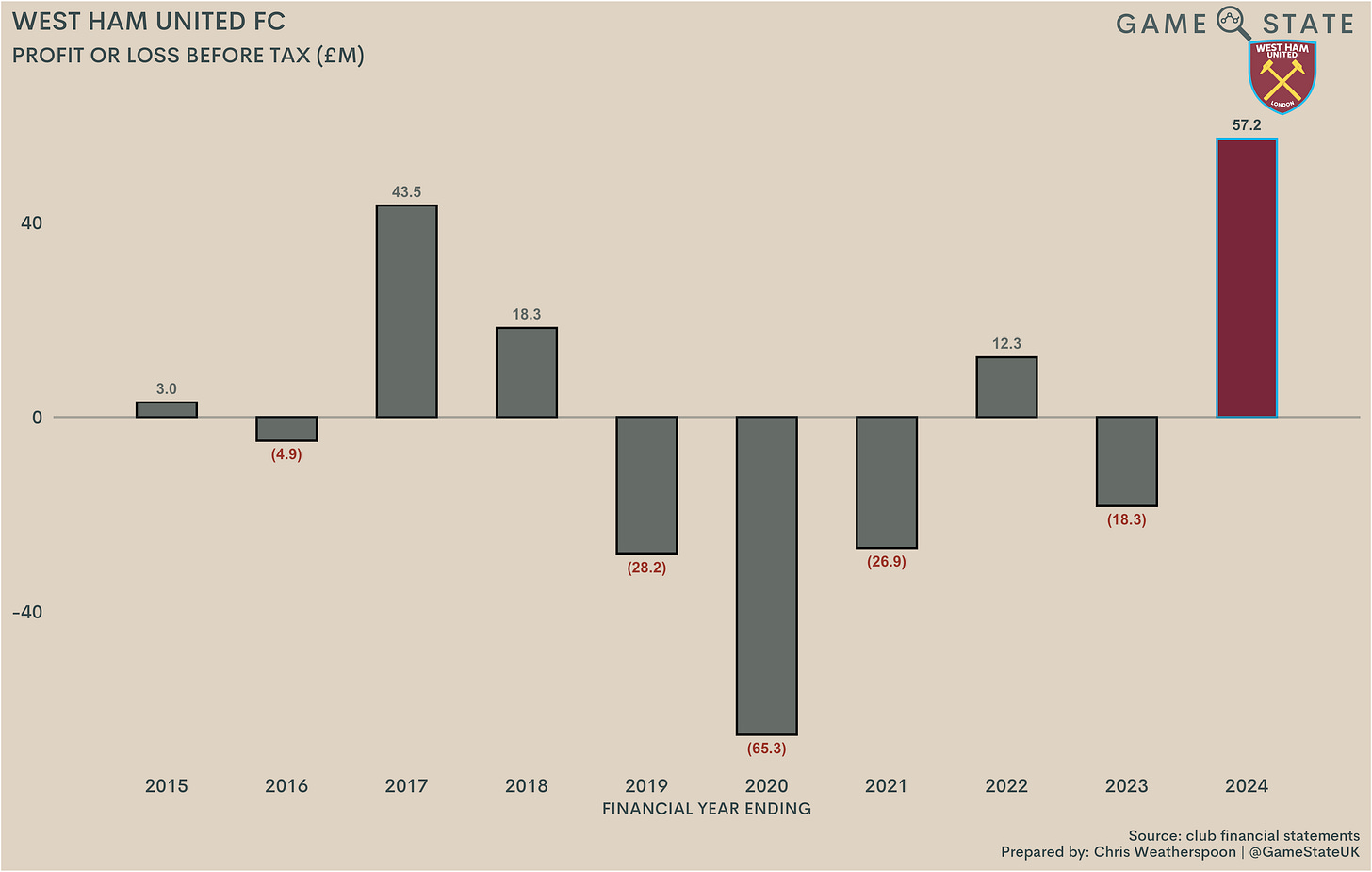

It is a quirk of the accounting calendar that both of those events fell into West Ham’s 2023/24 financial results. The club’s financial year end is 31 May - not unique among football clubs, but different to the 30 June date most adhere to - meaning both that European final and Rice’s sale to The Gunners formed part of last season’s figures. Both therefore contributed to West Ham’s healthy £57 million profit last year, a new club record.

Indeed, financial club records tumbled across the board last season for The Hammers, something which again is not unique in modern Premier League (EPL) football. West Ham’s revenue improved by £33 million (14 per cent) to a new high of £270 million, primarily due to a £19 million improvement in broadcast income. Commercial income rose a healthy £10 million (21 per cent) too, though that total income uplift was swaddled by extra player costs. Between a new club record wage bill and increased transfer fee amortisation expenses, player-related costs increased by £42 million.

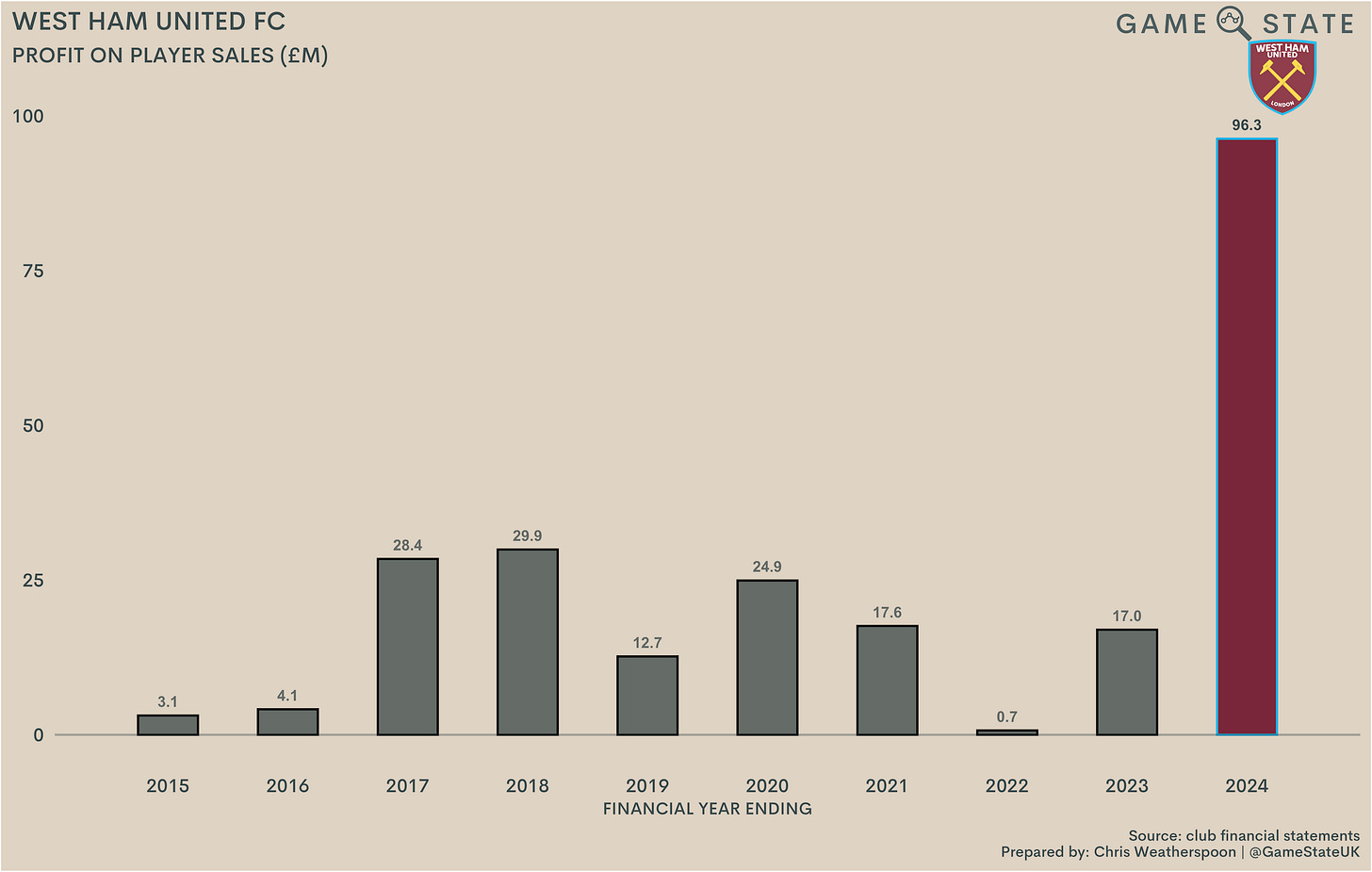

So was the sale of Rice in July 2023 that was the primary contributor to the club’s £18 million 2022/23 turning into that £57 million profit. Rice’s departure was the main driver behind West Ham booking £96 million profit on player sales last season, a £79 million improvement on a year earlier and another club record.

The Hammers finished ninth last season, their 12th consecutive year in the top flight. That was a five point improvement on a year earlier but, crucially from a financial point of view, it means no European football for the club in 2024/25, after three consecutive seasons of qualifying for UEFA competition.

Profit and loss account

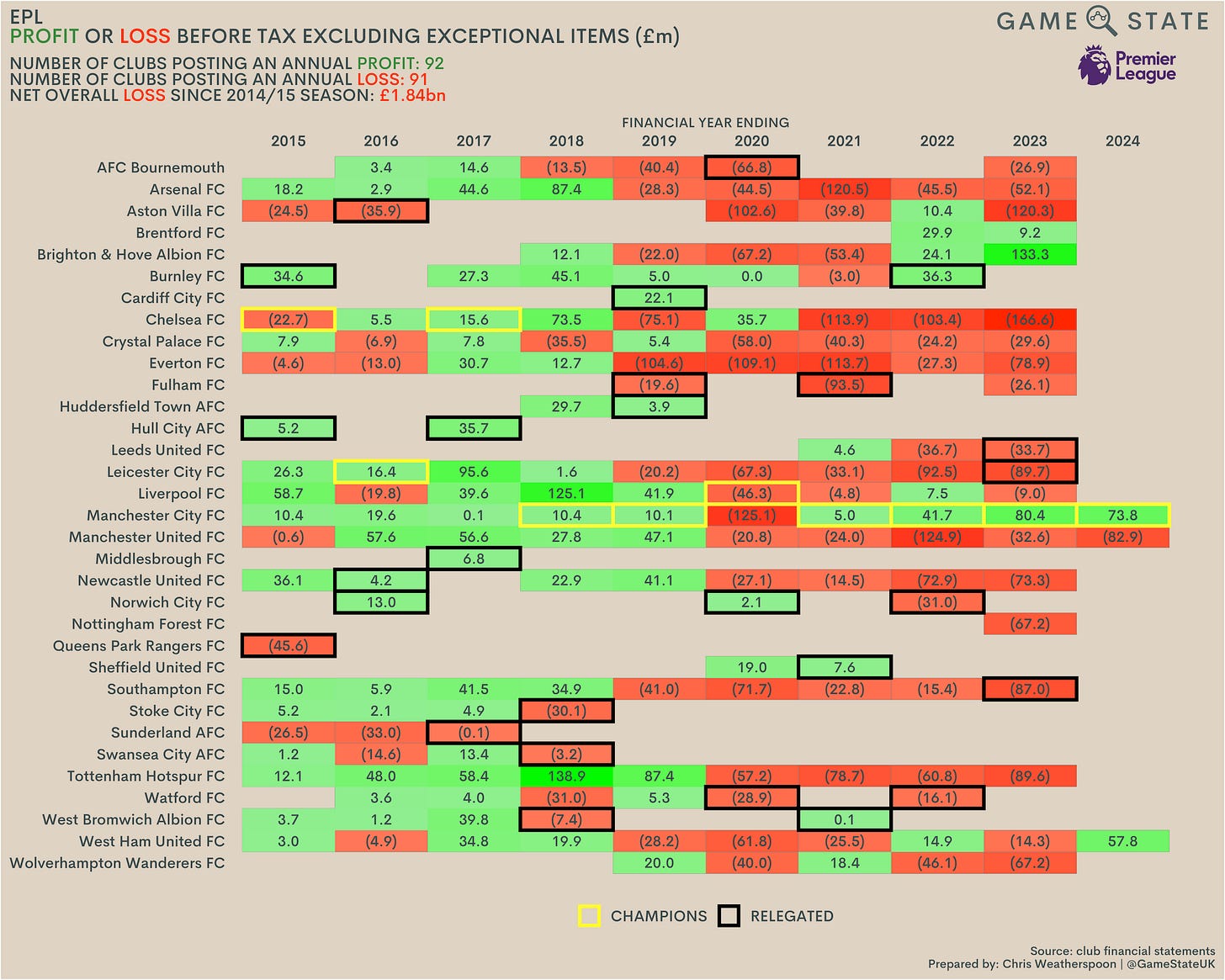

There has been little uniformity to West Ham’s bottom line over the last decade, with the club fluctuating between profits and losses, recording five of each since 2015. Having said that, the losses generally outstripped the gains; last season’s record profit still left the club in a net deficit position over the last 10 seasons, with the last decade totalling a £9 million pre-tax loss.

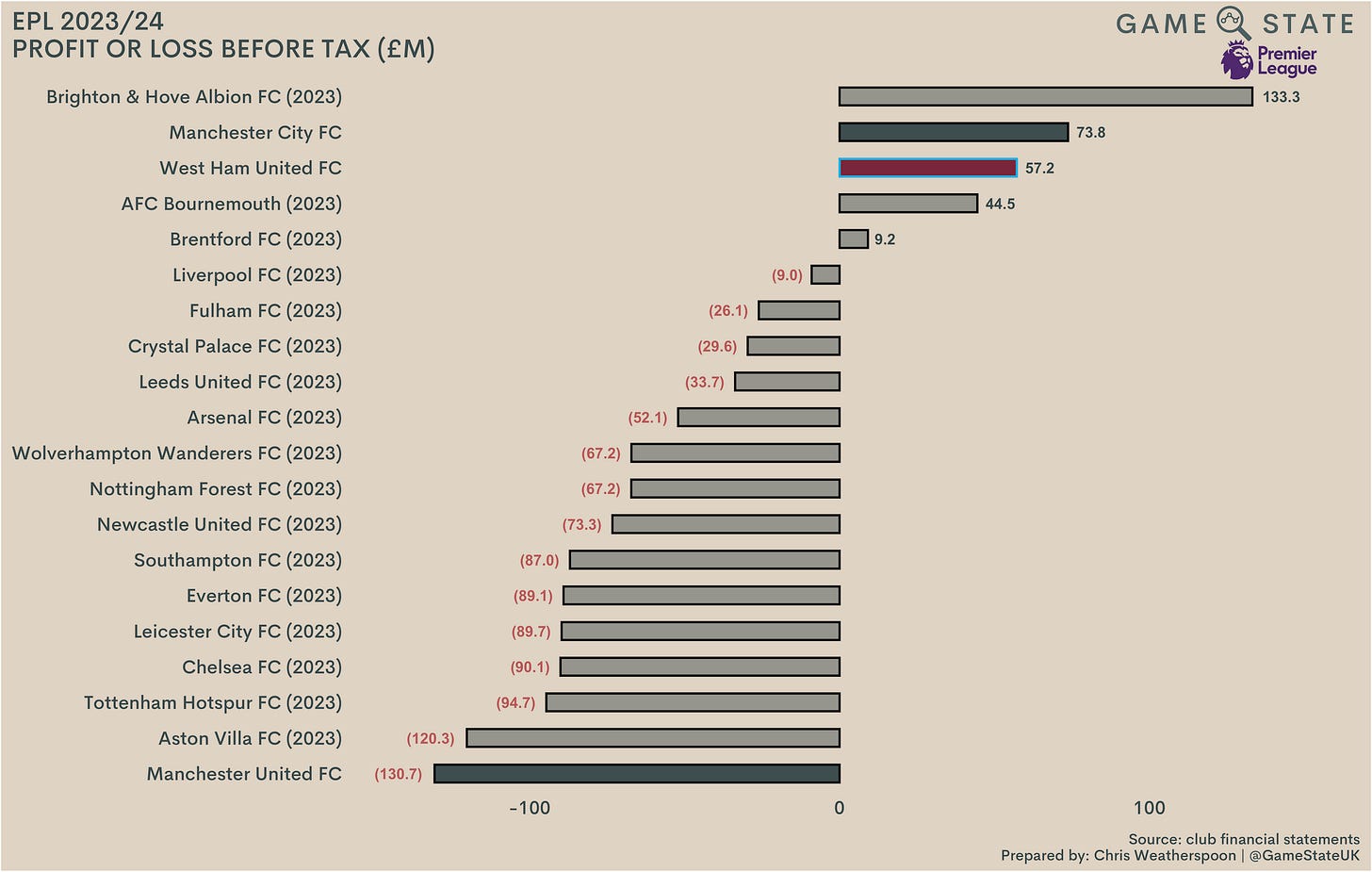

West Ham are only the third EPL club to release 2024 financials, and their £57 million loss slotted between the two Manchester clubs: City booked a £74 million profit, while United lost a galling £131 million. West Ham’s surplus is undoubtedly impressive by divisional standards, and actually sits third when we compare the most recently available figures. Looked at that way, The Hammers are one of only five profitable clubs, with the combined net annual loss across the EPL’s 20 teams sitting at £742 million.

After a buoyant period in the mid- to late-2010s, EPL club finances have nosedived. The Covid-19 pandemic set that particular ball rolling, but there’s still little sign of clubs recovering en masse. Of the 63 annual pre-tax results of EPL clubs since 2021, only 17 were in the black. To West Ham’s credit, they account for two of those.

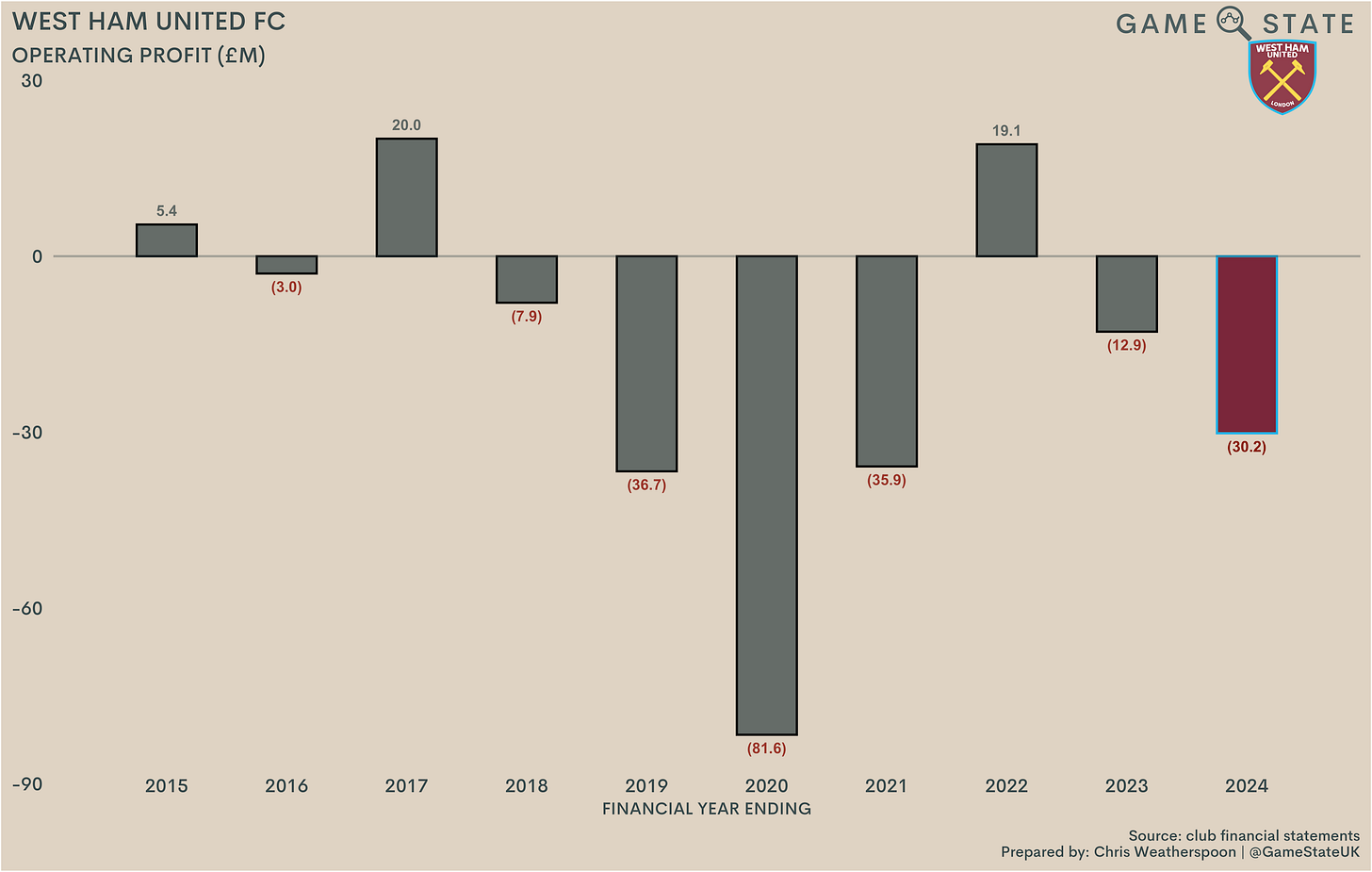

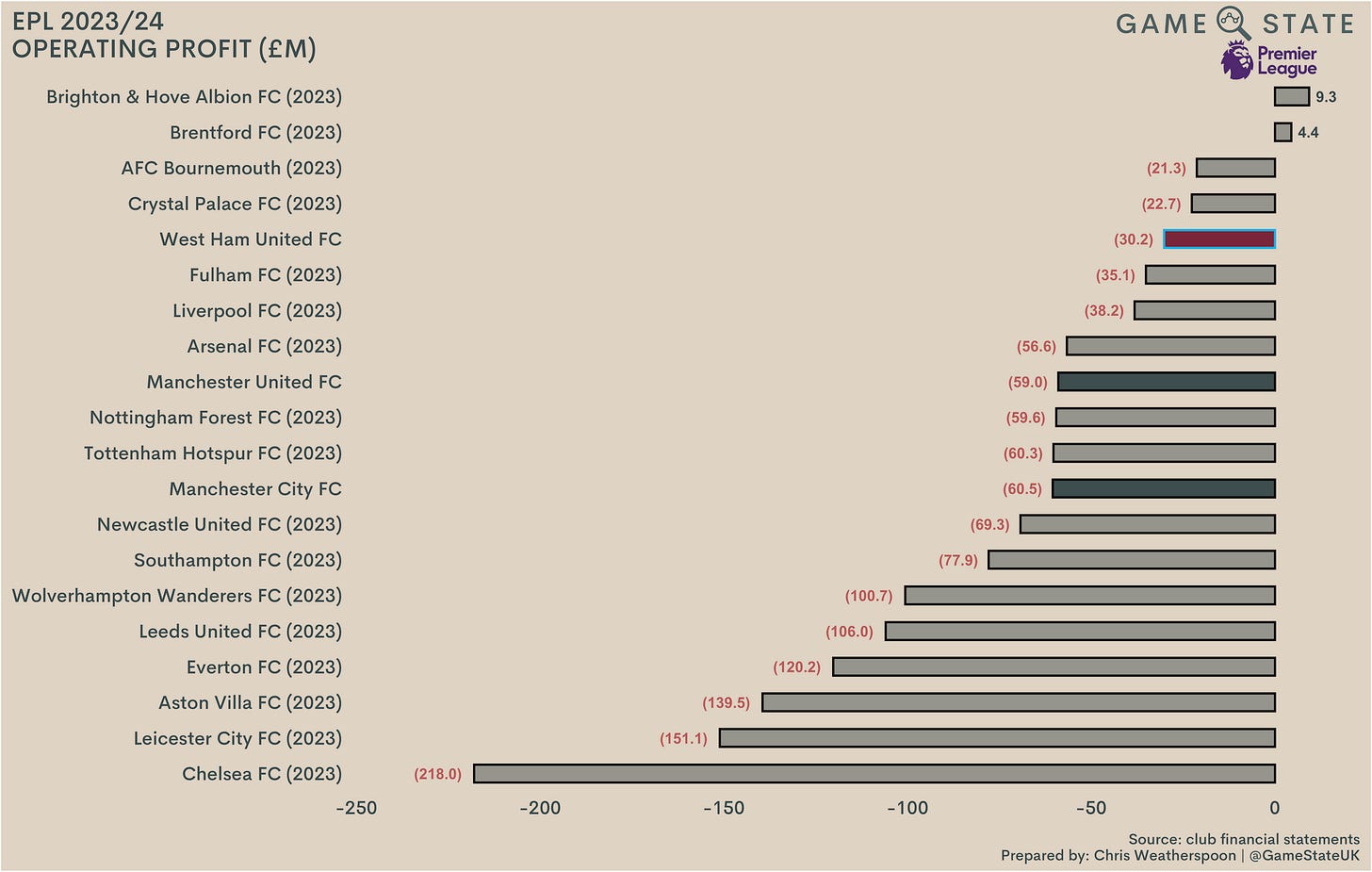

At the operating level, which strips out player profits, The Hammers’ result was considerably worse, with a £31 million loss, £17 million (134 per cent) greater than a year earlier. That’s still some way below the record £82 million operating loss when Covid arrived in 2020, but it should be of some concern that club record losses still resulted in an operating losses equivalent to £592,000 a week. In all, West Ham’s operating loss over the last decade totals £164 million.

It’s a sign of the times that losing nearly £600,000 a week at the operating level is still one of the best results in England’s top tier. Indeed, it reflects how clubs increasingly rely on player sales to boost their bottom line. Based on most recent figures, the division’s collective annual operating loss sits at £1.4 billion.

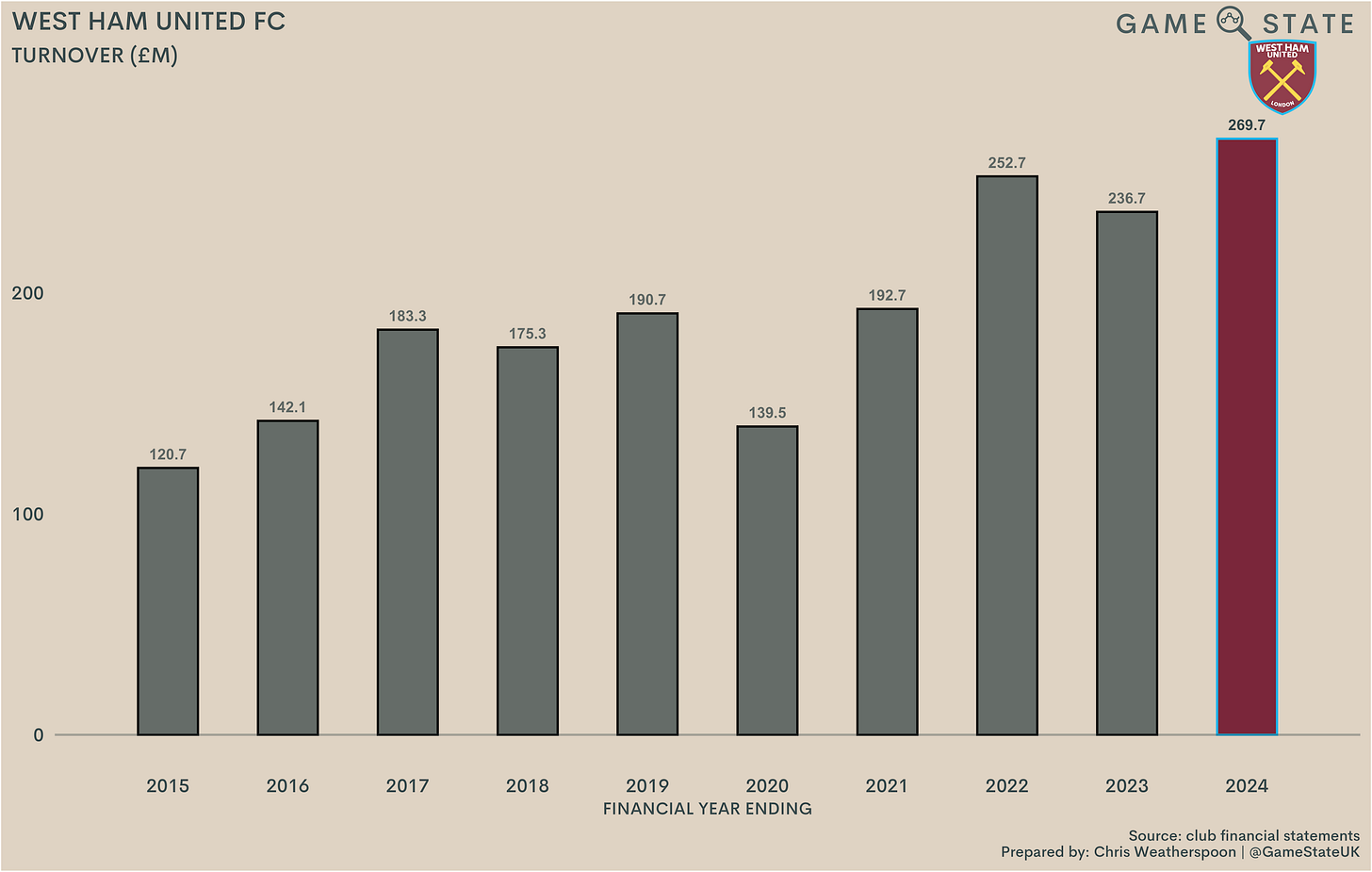

Turnover

West Ham’s turnover hit a record £270 million last season, up 14 per cent on 2023 and £17 million higher than the previous record set in 2023. In the last decade, The Hammers’ income has increased by £150 million, a sign of both the continued growth of the EPL TV deal but also significant increases in the club’s other revenue streams. In total, West Ham have booked £1.904 billion revenue in the last 10 years.

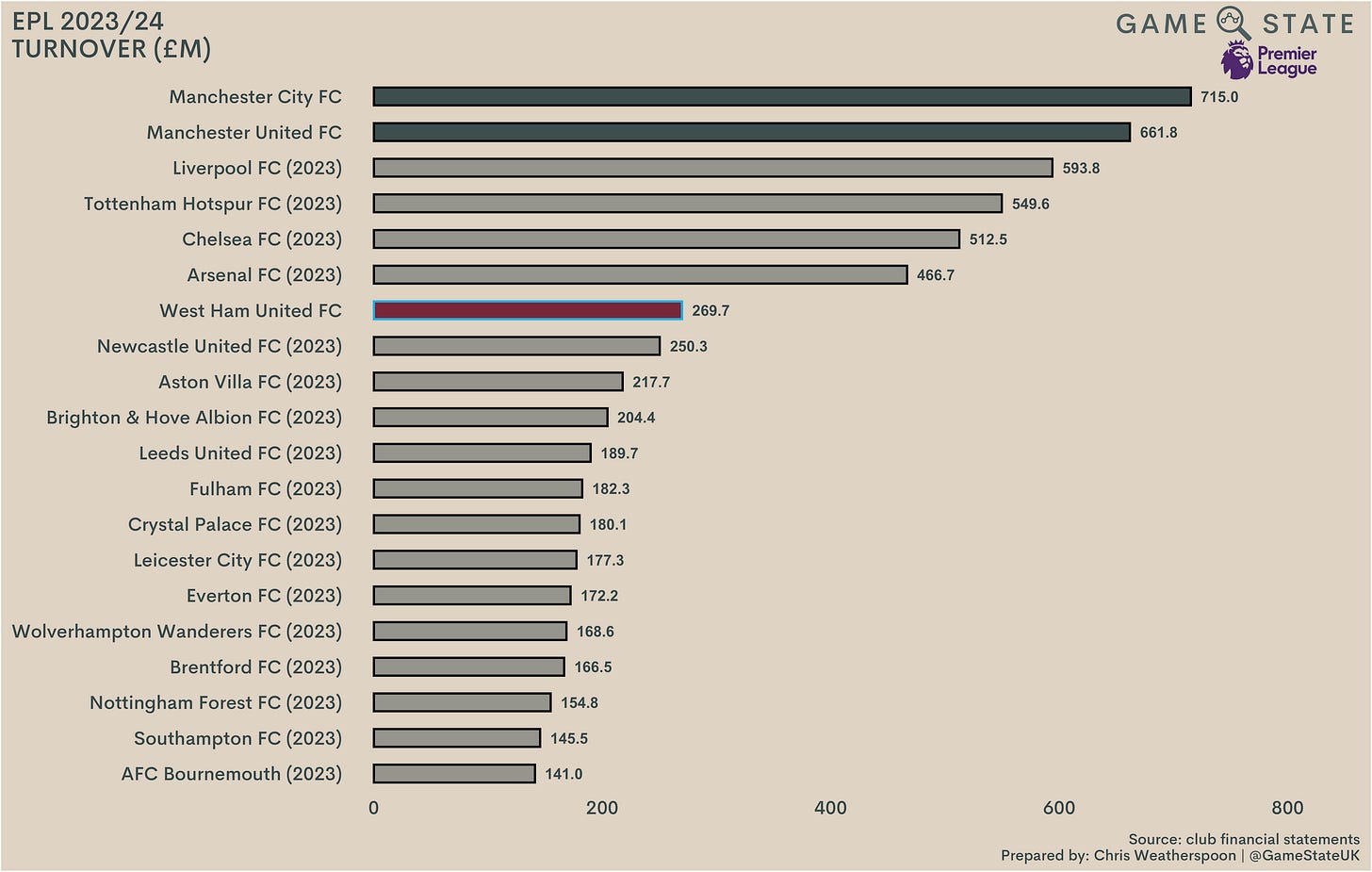

That £270 million currently pits The Hammers as the best of the rest, trailing the league’s famed ‘Big Six’ but leading all others. That will change soon when Newcastle United release their 2024 financials, as their revenue will be around the £300 million mark following their stint in the Champions League, but it still marks a strong showing. EPL clubs’ most recent annual incomes total £6.2 billion, though over half of that (57 per cent) accrues to just six clubs, with those biggest earners generating £3.5 billion amongst themselves.

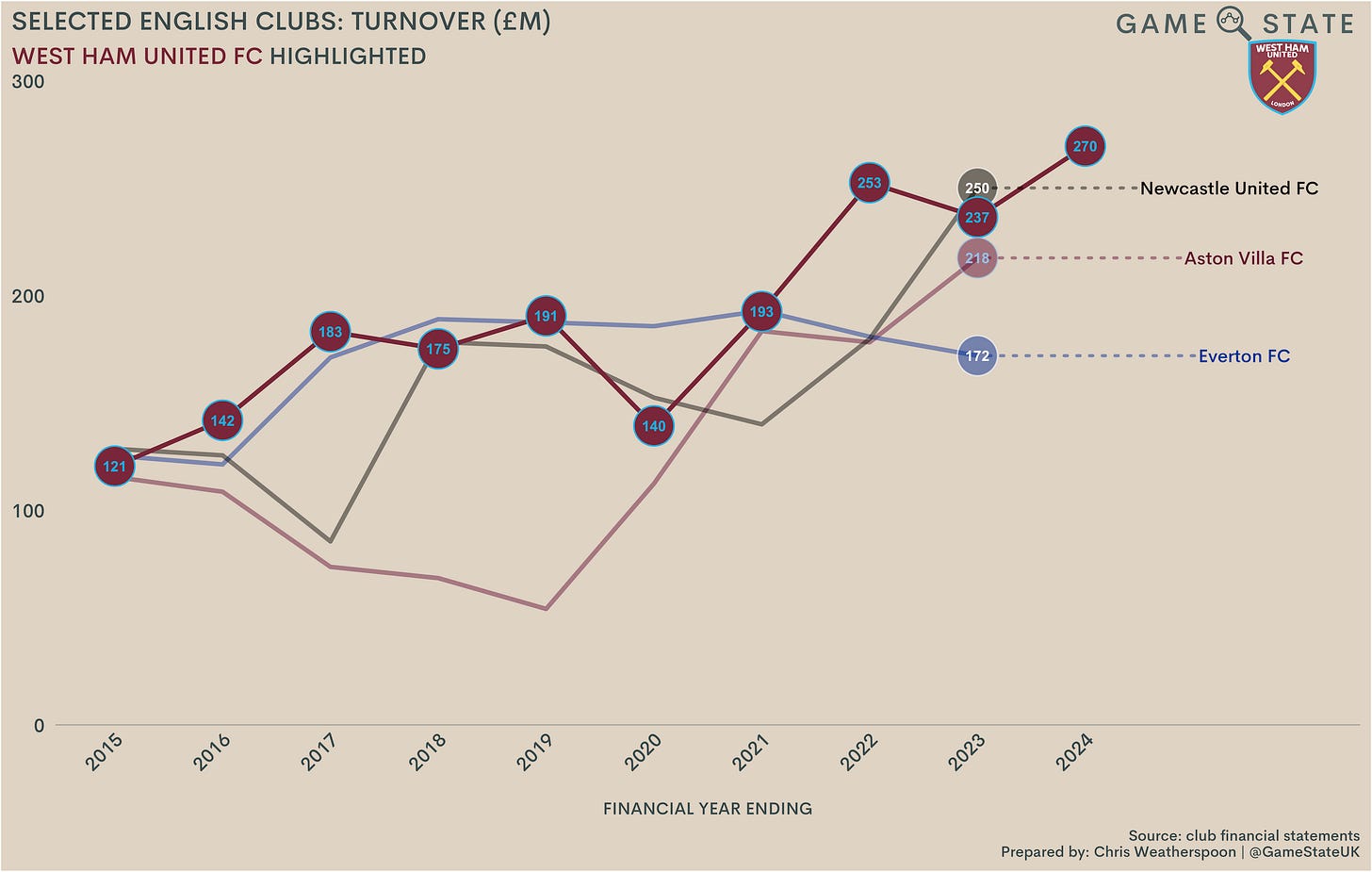

As West Ham sit as the best of the rest currently, it’s worth considering the club’s recent income growth against some selected peers: namely Newcastle United, Aston Villa and Everton, all historically ambitious clubs who have spent much (or all) of the last three decades in the top tier.

In the last three seasons, West Ham have consistently been near the top of this cohort when it comes to turnover, and were some way ahead of the others in 2022. That has changed now though. Newcastle’s 2024 income will have outstripped West Ham’s once The Magpies’ accounts are published, meanwhile Aston Villa should skip past both clubs this term as they undertake their own Champions League foray.

West Ham’s blushes have been spared somewhat by Everton (who themselves may be in line for a resurgence following their recent takeover), but club’s owners will doubtless be disappointed the team wasn’t able to capitalise on recent success and progress closer to, or into, participation in the Champions League.

Matchday income

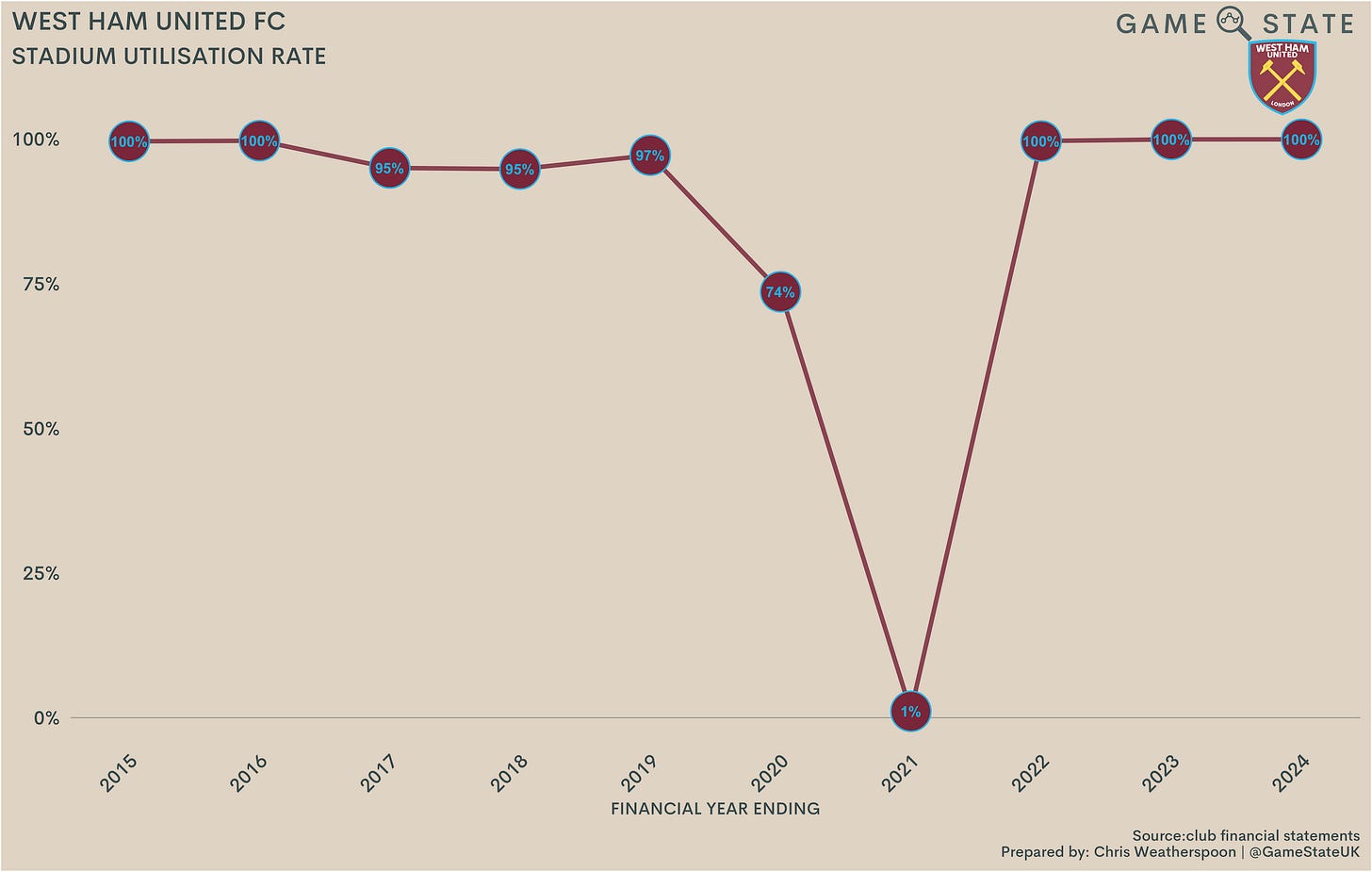

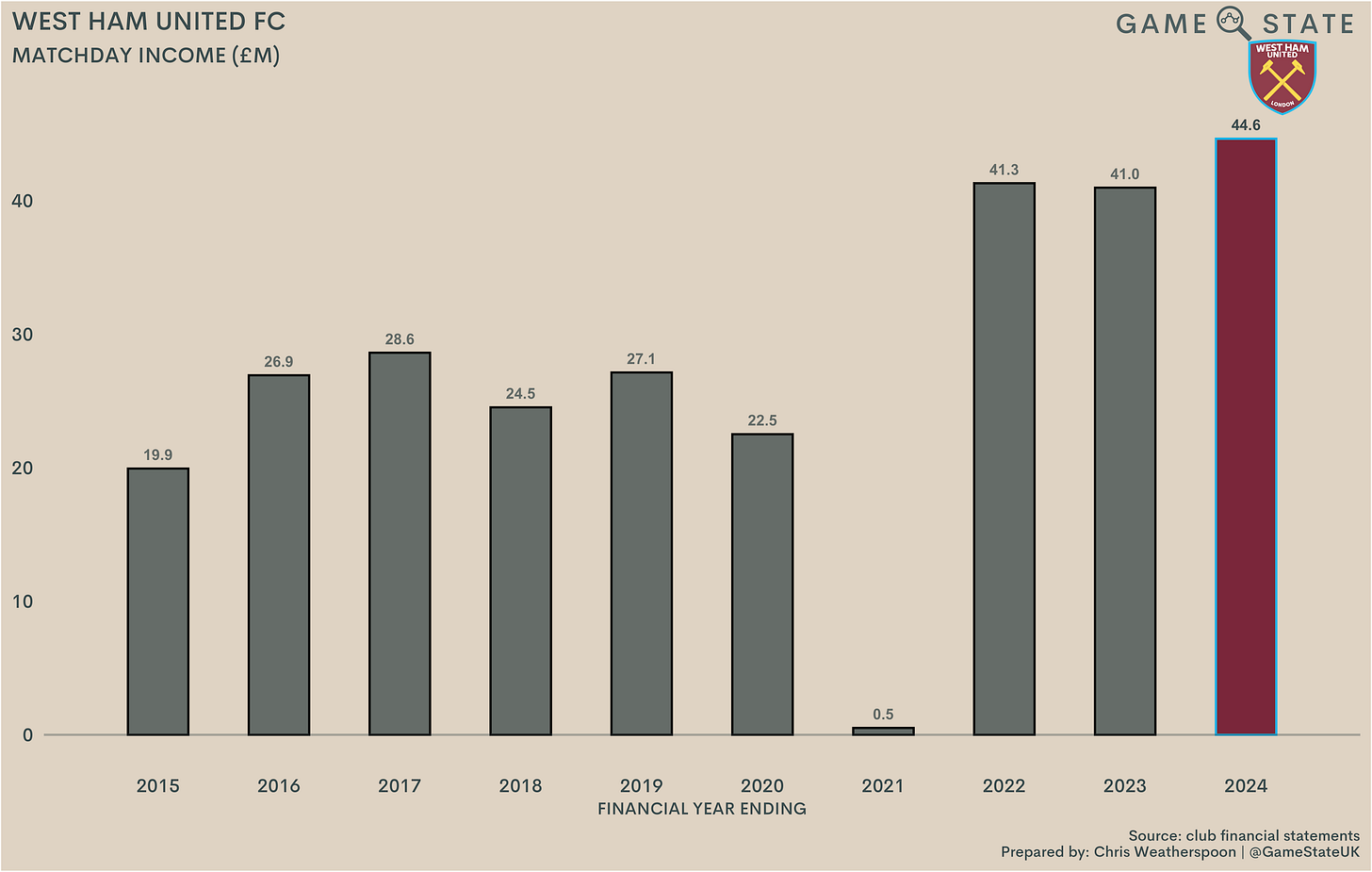

West Ham underwent a move to a bigger stadium in 2016, but there’s clearly been sufficient demand for the club’s new home, even if plenty of fans have been critical of its suitability as a football ground. Leaving Upton Park for the London Stadium saw the club’s home capacity nearly double to over 62,000, but Hammers fans have generally filled their ground, with league games pretty much sold out across the three seasons since the end of pandemic-induced attendance restrictions.

The result of that near doubling in attendances has been significant financially. In their final year at Upton Park, West Ham banked matchday income of £20 million. Last season, that figure was £45 million, a new club record. Gate receipts have risen markedly since fans returned to stadia in 2022, a combined of that increased average attendance and an uptick in home matches, generally owing to participation in European competition.

Another increase is expected this season, though the driving force behind it is a controversial once. Hammers fans were greeted with a spate of ticket price increases ahead of the 2024/25 season, with concessions not only costing an average of 7.5 per cent more but also seeing a reduction in their availability around the London Stadium. West Ham are far from alone among EPL clubs in jacking up prices recently; their fans are far from alone in expressing dismay in response.

Separately, the club continue to push for every more match-goers to be allowed in. The allowed number of attendees at the London Stadium has steadily risen in recent years, up from the 57,000 available seats when West Ham moved in 2016, even though a further 5,500 seats currently sit unused on matchdays. The Hammer’s current licence limits their capacity to 62,500, but discussions have been held about increasing that to 68,000, with the club hopeful an agreement can be reached and in operation for the start of the 2026/27 season.

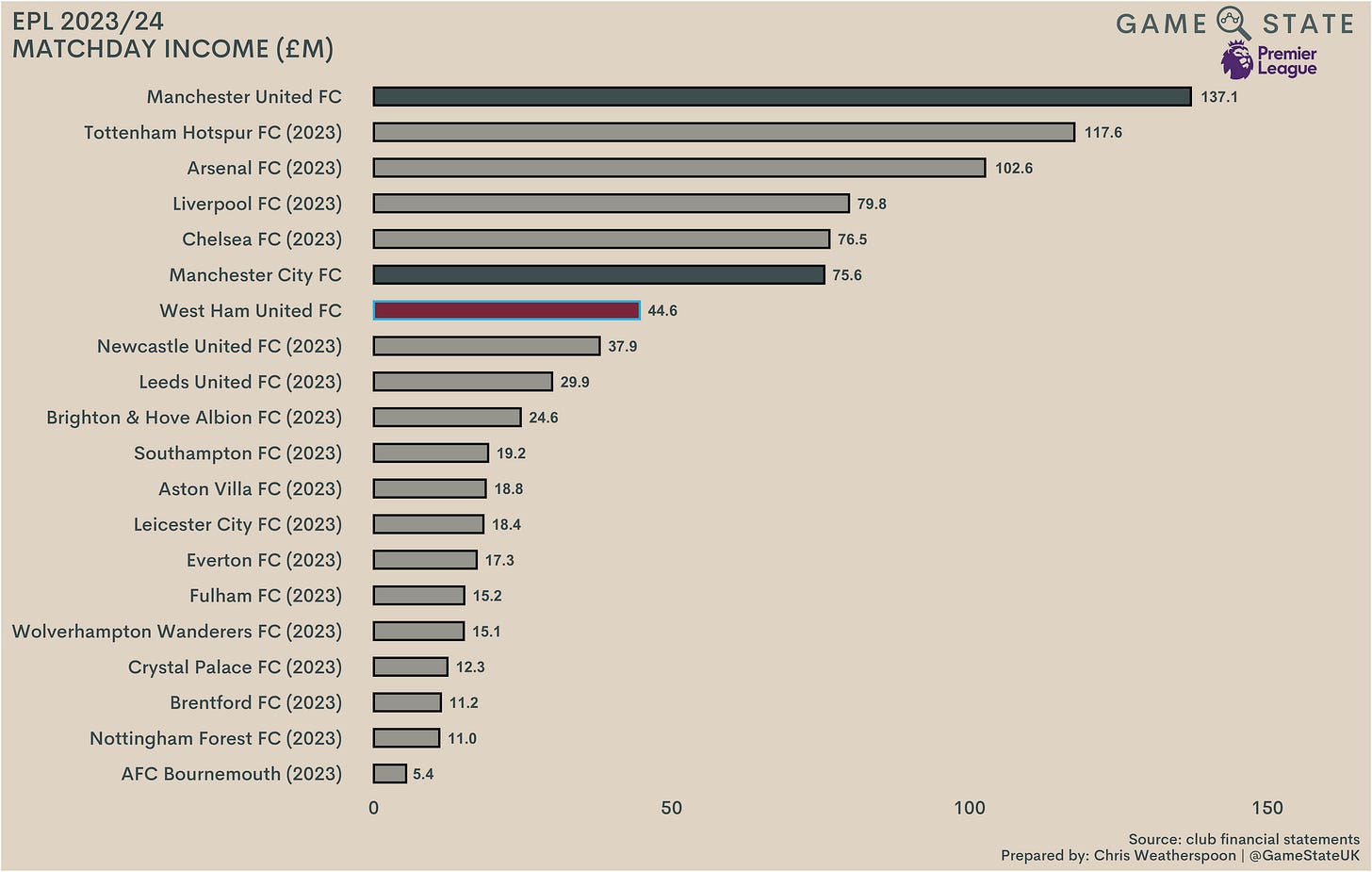

Just as they sit seventh in the overall income table, so West Ham’s gate receipts are currently the best outside the Big Six. Again, expect that to change once Newcastle release their results, and while West Ham’s matchday income is undoubtedly among the highest in England it’s also hard to argue that’s especially surprising given the size of the club’s ground.

That ground has been cause for controversy for years, with West Ham only renting it at what many see as a peppercorn figure. Last season saw the club pay £4 million in rent for the London Stadium, a slight increase on a year earlier but still a pretty sweet deal for the club.

In all, since moving on from Upton Park in 2016, West Ham have paid £25 million in operating lease costs on land and buildings, the vast majority of which relates to the London Stadium.

In combination with the £15 million up-front payment the club agreed to pay to the London Legacy Development Corporation (LLDC) upon commencement of its 99-year lease on the ground, that takes the total the club has spent on its new home to £40 million. The ground itself cost £429 million to build for the London 2012 Summer Olympics, and a further £272 million to convert it into a football stadium, taking the total cost to £701 million.

E20 Stadium LLP, the LLDC subsidiary who sub-lease the stadium to the club, regularly make eight-figure annual losses due to the costs they, rather than West Ham, foot in running the stadium, while the lease agreement is so disadvantageous to LLDC that the stadium was valued at less than £1m in the company’s latest accounts to the end of March 2024. While The Hammers’ rent costs will rise rise with inflation, so far they’ve spent £40 million in exchange for eight years of using a £700 million-plus asset, and they’ve enjoyed a huge increase in their gate receipts as a result. Little wonder the lease agreement has repeatedly been described as the “deal of the century” - and has invoked the ire of those dismayed that the British taxpayer is, in effect, paying to host an EPL club.

Broadcast income

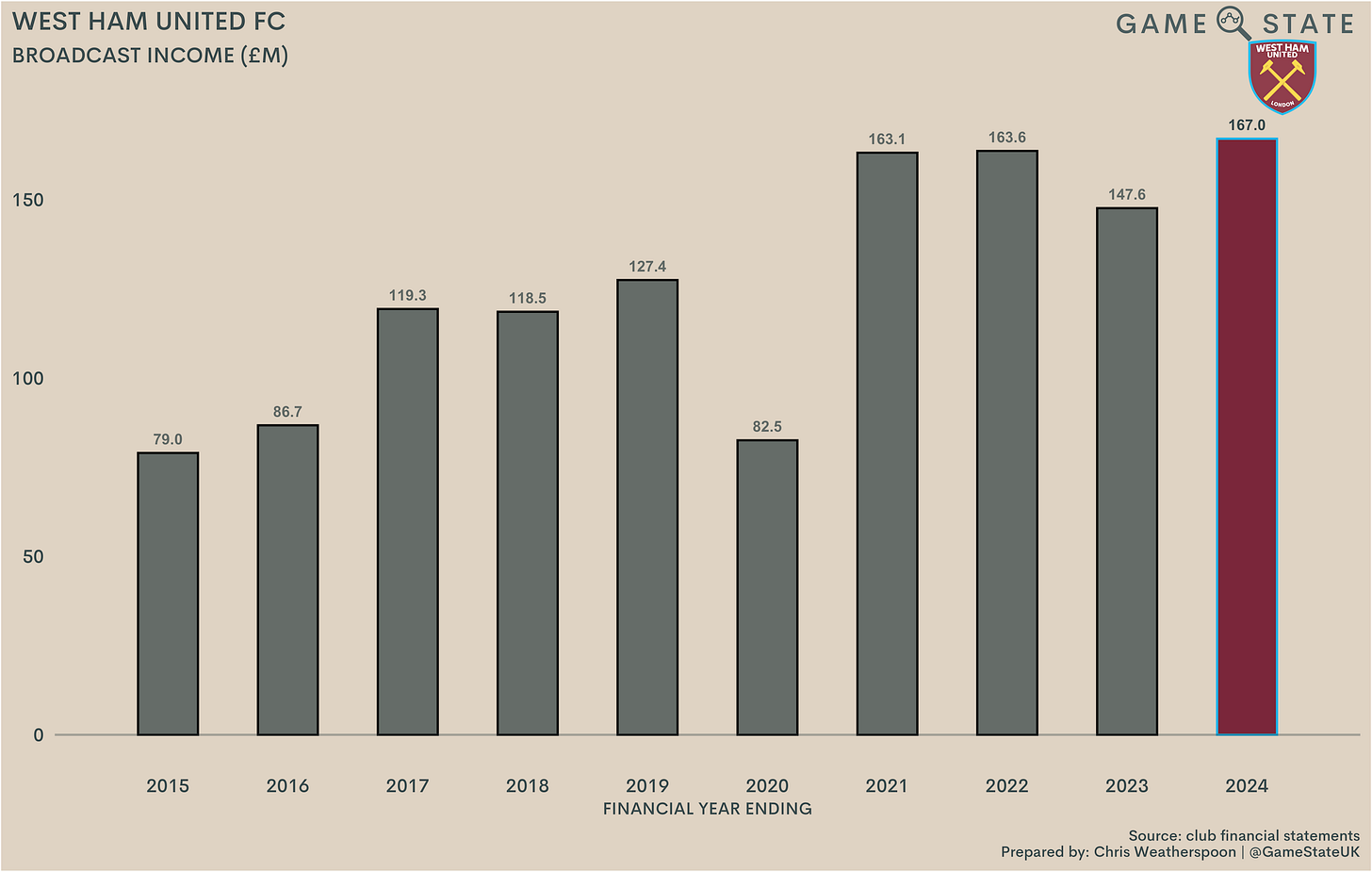

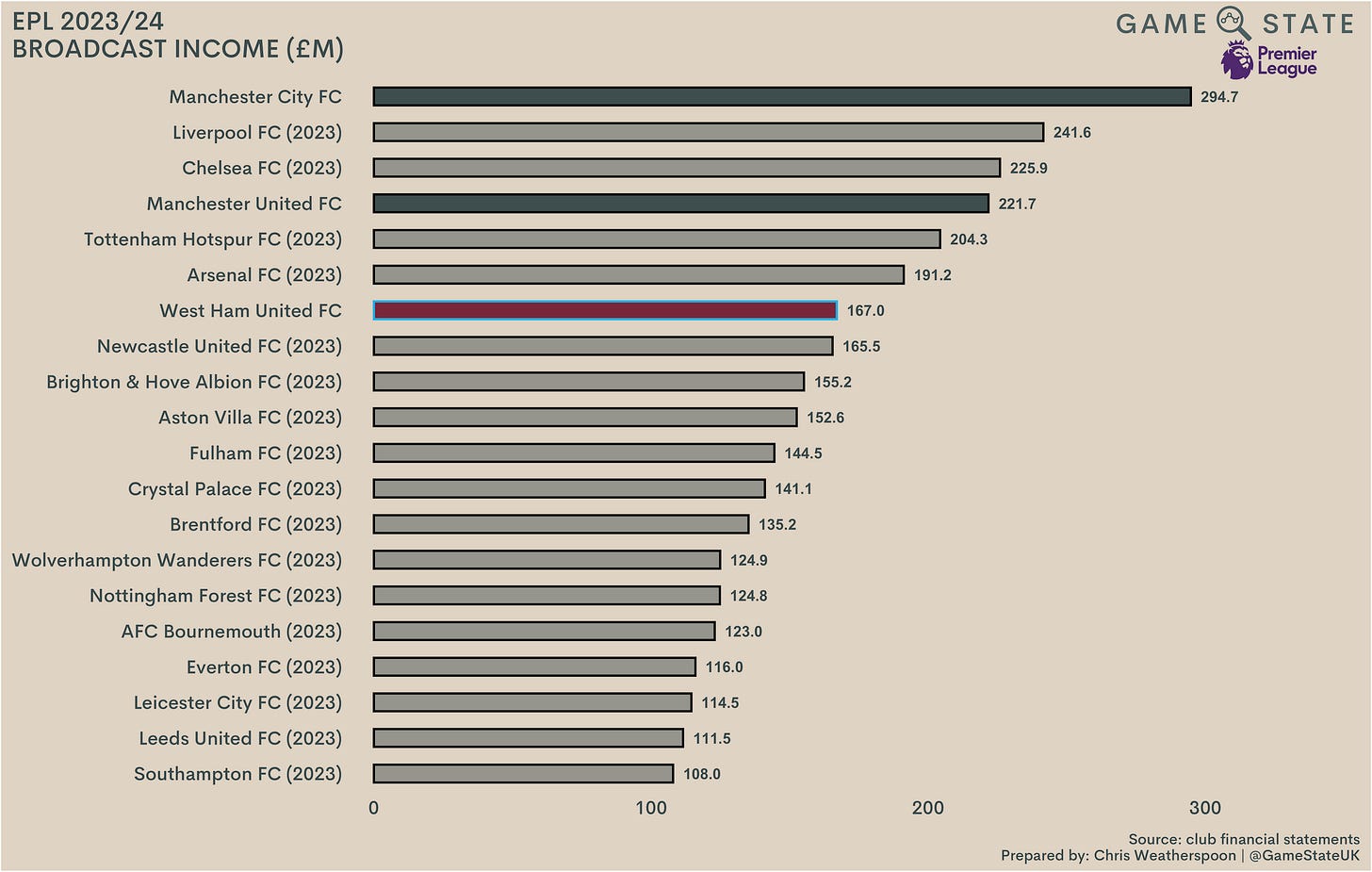

West Ham banked £167 million in broadcast income in 2023/24, a little more than the previous high of two years earlier. That comprised the highest slice of last season’s turnover at 62 per cent, which is a smidge below the club’s 10-year figure in that regard. The Hammers’ £1.255 billion TV money since 2015 was 65 per cent of total income in that time.

Just as West Ham’s revenue currently sits seventh in the EPL, so too their broadcast income. The gulf to those ahead isn’t so vast here, owing to both the EPL’s attempts to share TV money with at least some sense of parity, and The Hammers’ participation in the Europa League last season. Even so, they did still trail Manchester City by around £130 million. In all, EPL clubs banked a combined £3.3 billion in broadcast income.

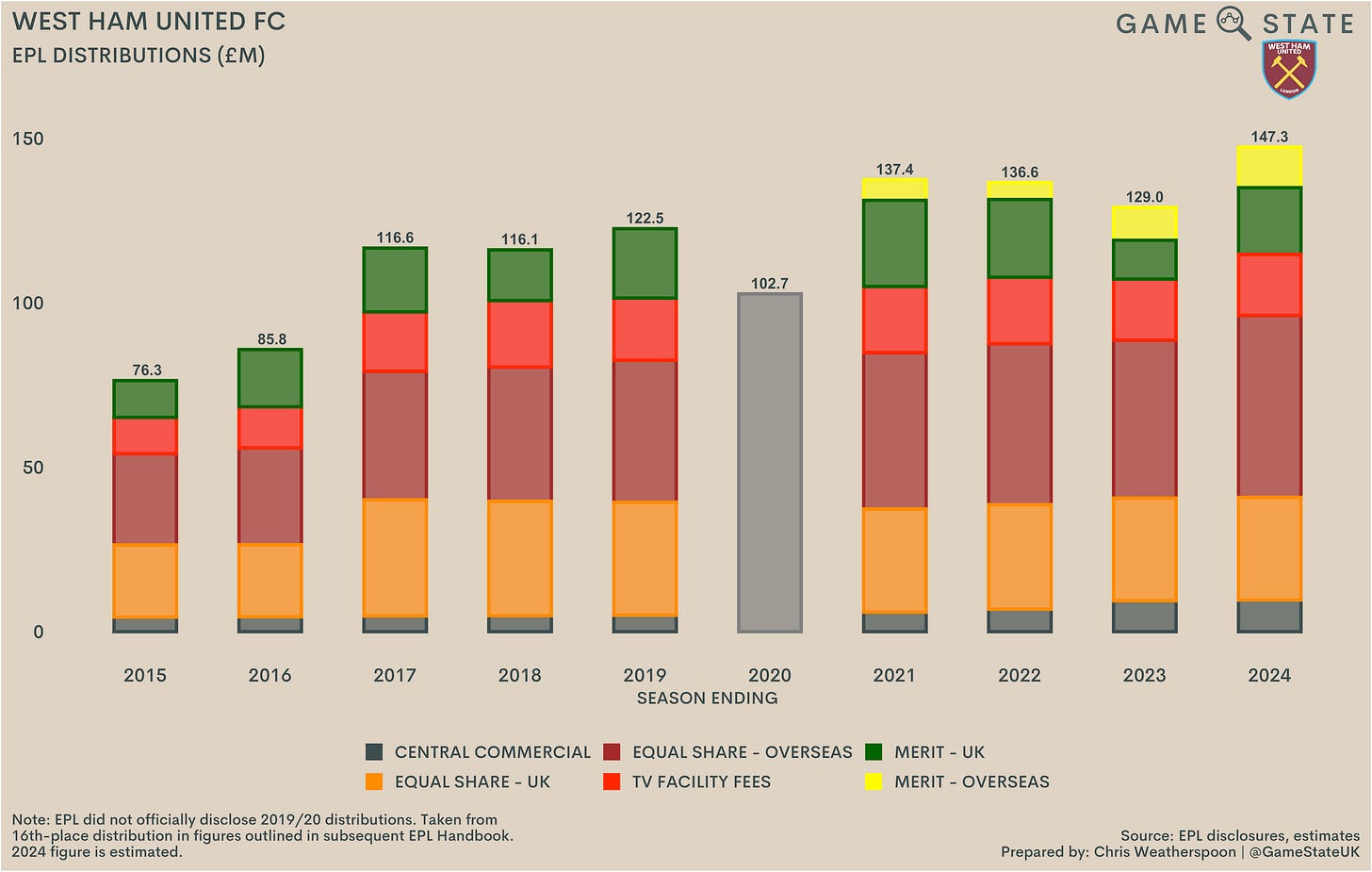

West Ham’s broadcast income was up £19 million (13 per cent) on 2023, primarily as a result of a higher EPL distribution. The league hasn’t yet disclosed club distributions for 2023/24, so we’ve had to rely on our model, which projects that West Ham earned £147 million from the EPL last season, an £18 million increase on a year earlier.

The two drivers of that increase were an increased merit payment, as The Hammers finished five spots higher than in 2023, which we estimated increased by £11 million (split £9 million from the domestic merit pot, £2m from international). Separately, an increase in the value of league’s TV deals saw the amounts distributed equally to clubs increase; our model estimates all EPL clubs received an extra £7 million each last season as a result. Note, however, that there is a caveat to these estimates, detailed at the bottom of this broadcast income section just below.

West Ham have played in the EPL for each of the last 10 seasons, in which we estimate the club has received £1.17 billion in TV money distributions from the league. The trend has generally been upward, with the exception of 2020. That season saw all EPL clubs forced to pay a rebate to TV companies out of their EPL prize money, and West Ham’s figure was lowered further by them finishing 16th that year, their lowest league finish in the last decade.

Our breakdown of estimated distributions to 2023/24 EPL clubs can be found below, though it’s worth reiterating that these figures could (and probably will) change one the EPL releases confirmed amounts in the next couple of months.

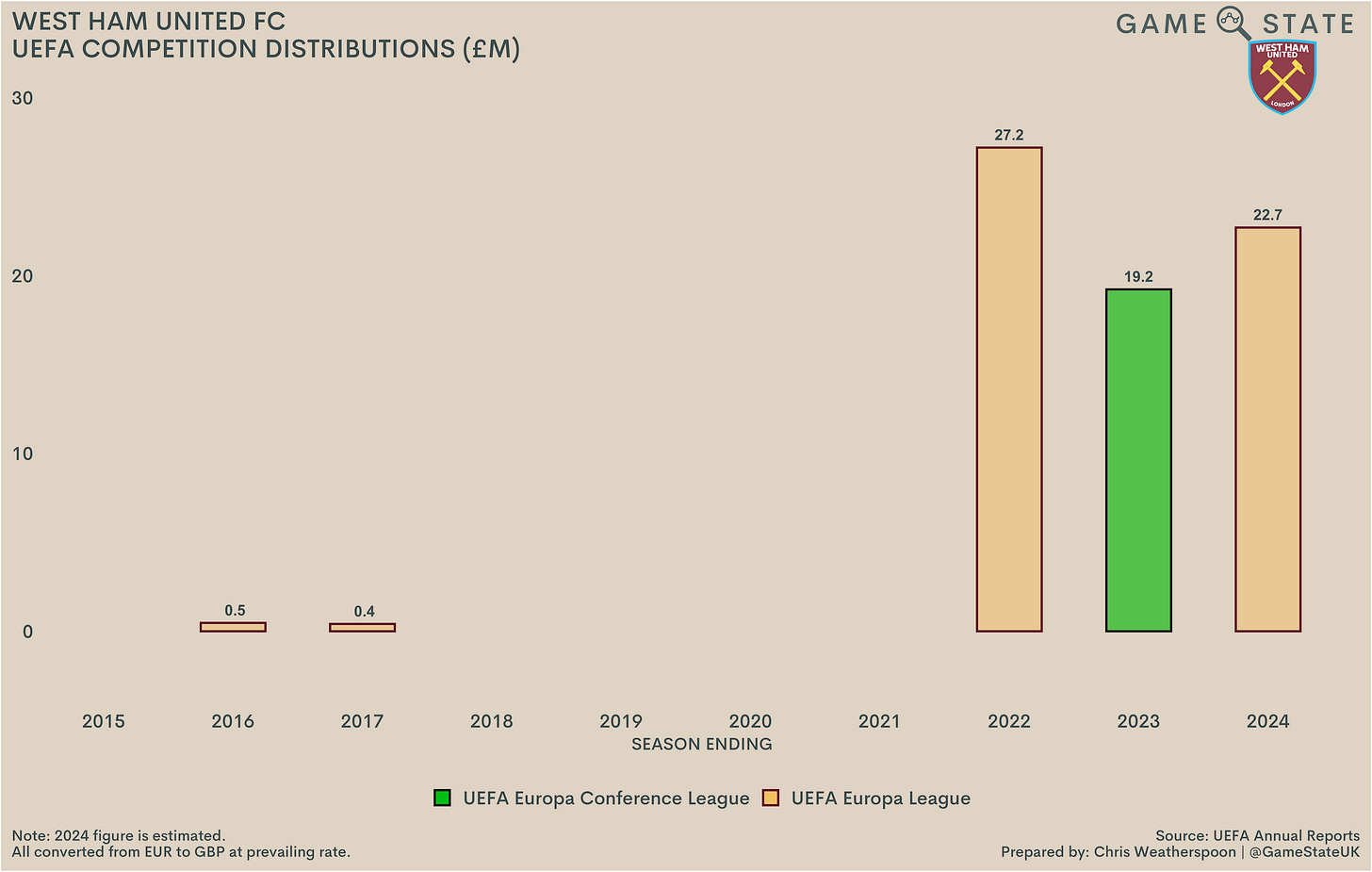

One notable boost to club coffers in the last three seasons has been a return to European competition, including that Conference League success. The way UEFA apportions money to its three club competitions means, oddly, that West Ham received the least in UEFA prize money in the season they actually won a competition, as the money on offer in the Europa League outstrips that of UEFA’s ‘third-tier’ tournament.

Across the past three seasons, The Hammers have earned an estimated £69 million in prize money from playing in Europe, a figure which doesn’t include any boosts to commercial or matchday income, the latter of which was helped by extra games being played, even though only the quarter-final against Bayer Leverkusen sold out last season.

As mentioned at the top of this piece, the timing of West Ham’s financial year end meant the 2023 Europa Conference League Final, and thus the club’s financial reward for winning it, fell into the 2023/24 accounts. As a result, the figures shown above don’t translate to the European income through the latest accounts; the club confirmed £1.7 million of 2023’s UEFA distribution fell into the latest financials. As a result, we estimate The Hammers will see a £24 million reduction in European broadcast income in 2024/25 as a result of failing to qualify for UEFA competition this season.

The keen-eyed among you will have noted that the combination of our estimates for The Hammers’ EPL and UEFA distributions adds up to a little more than the £167 million broadcast income declared in the latest accounts. Where the over-estimate lies will only become clear once both organisations disclose their distributions for the 2023/24 season.

Commercial income

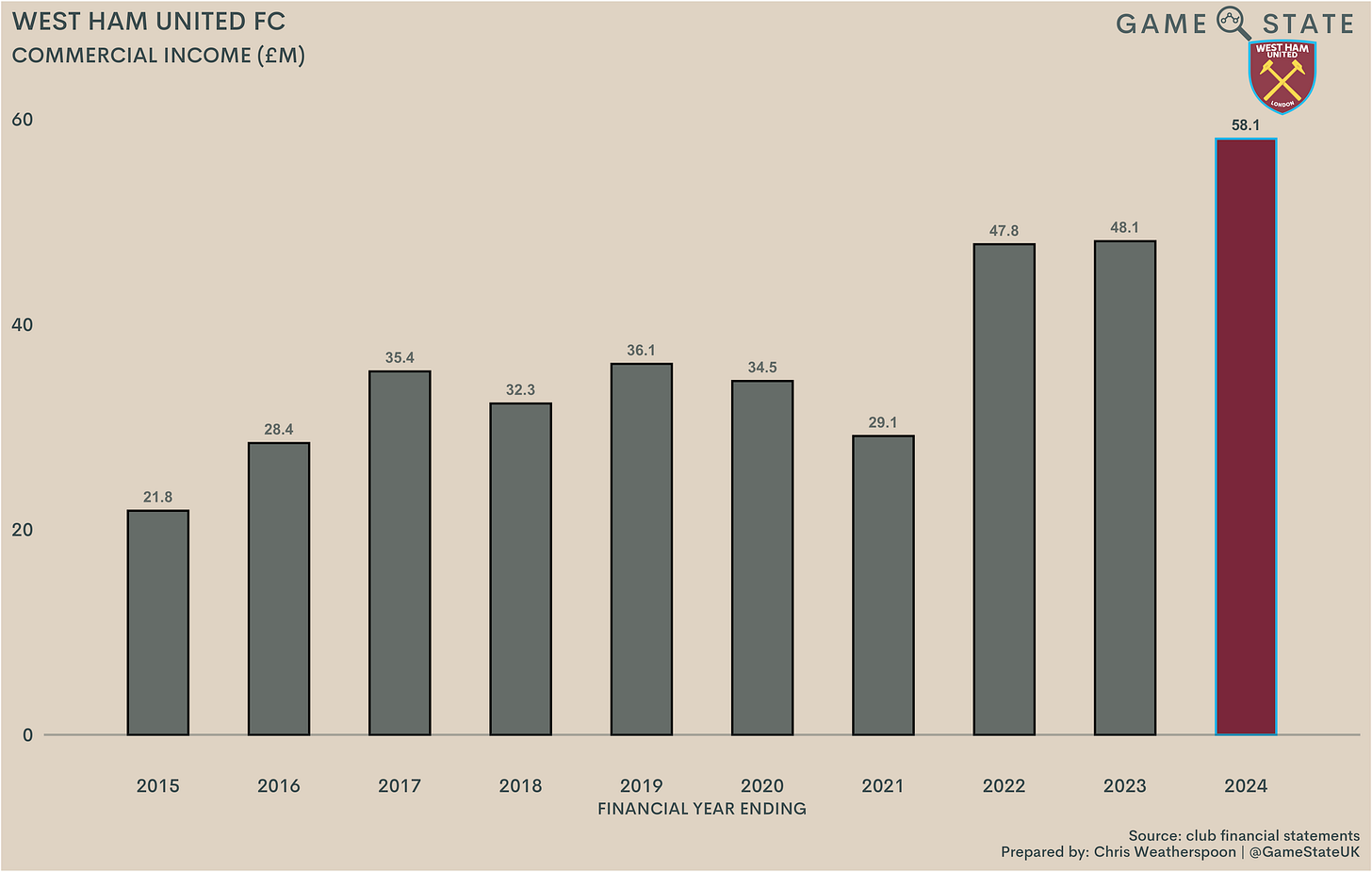

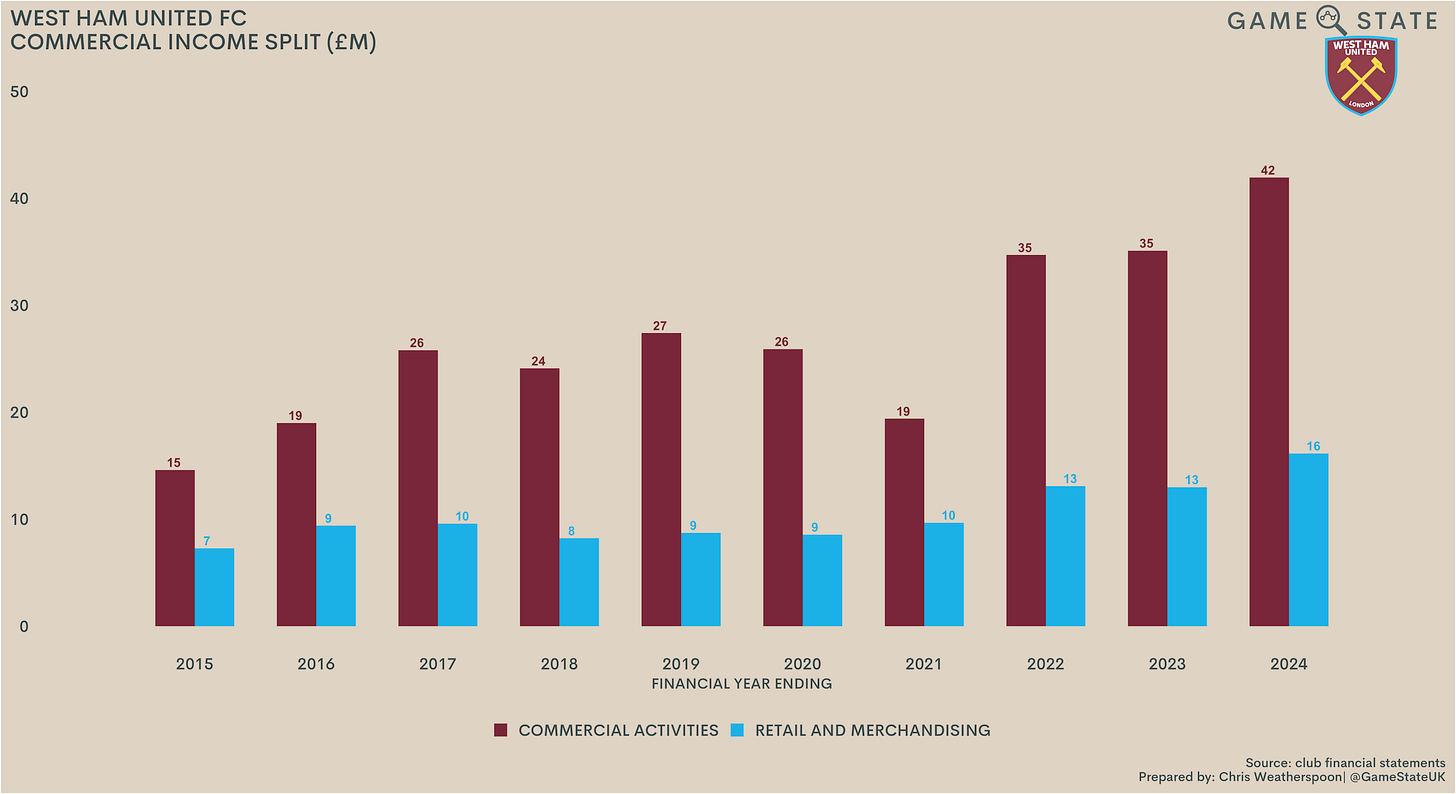

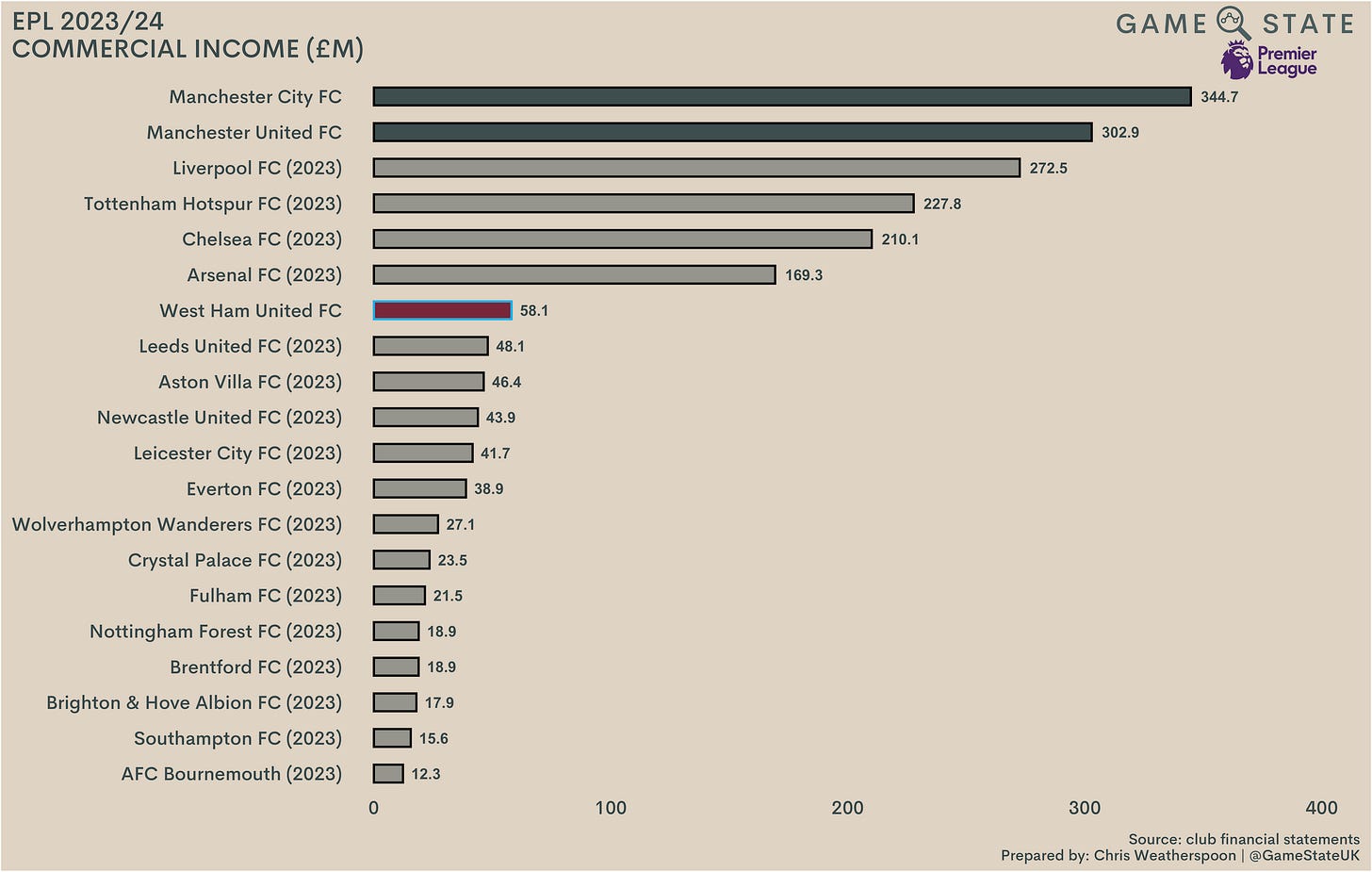

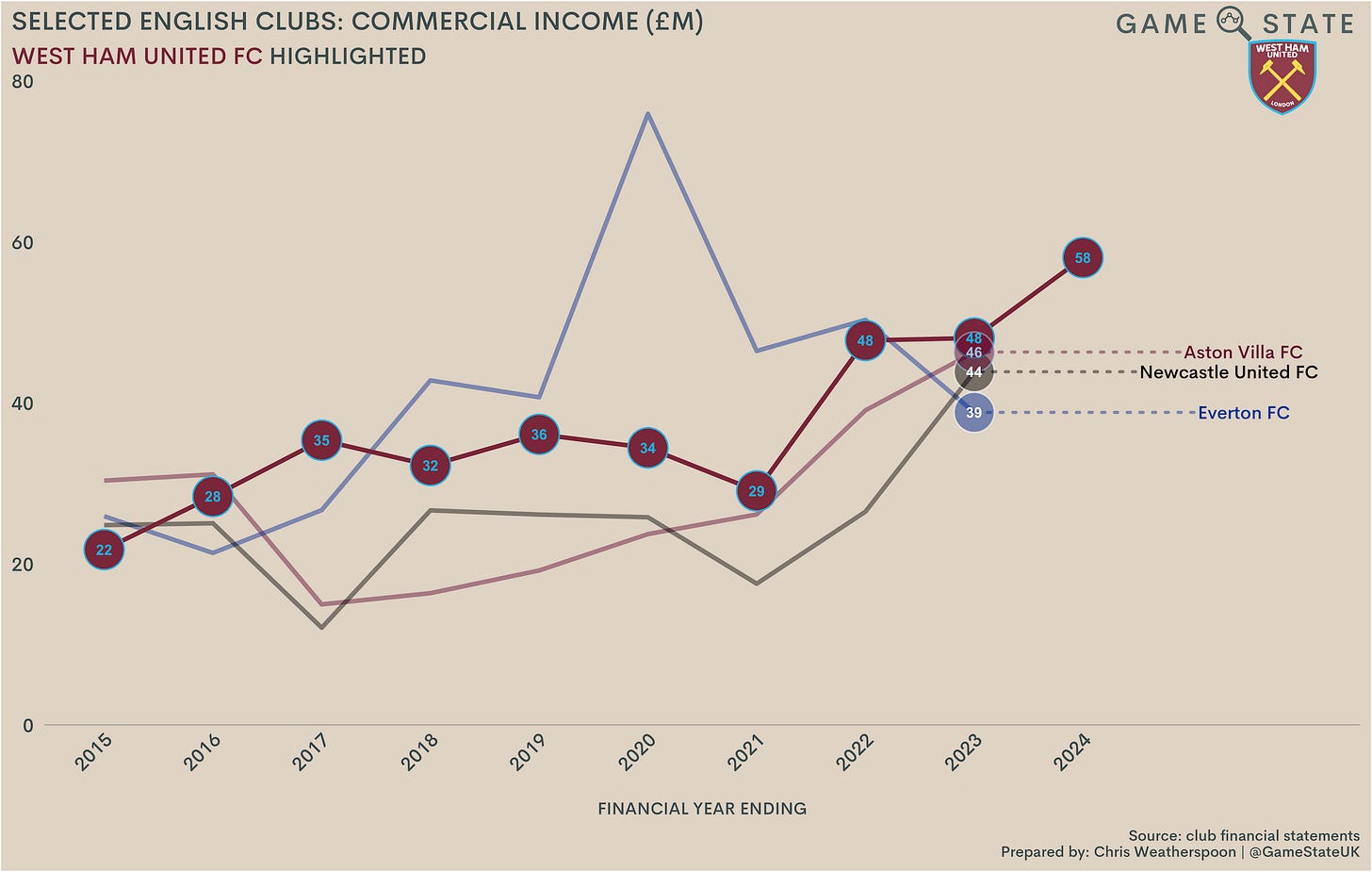

West Ham’s commercial income grew impressively last season, up £10 million (21 per cent) to a record £58 million. That was helped by playing in a higher level of European competition, though the club was in the Europa League two years prior and didn’t see commercial income at this level. Across the last decade The Hammers’ commercial income totals £372 million, and the owners will hope to continue the upward trend here, knowing full well that it is in the commercial realm that England’s biggest clubs continue to surge ahead.

West Ham don’t split out their commercial income in any great depth in their accounts, only disclosing figures for retail and merchandising and the rather nebulous ‘commercial activities’. Still, we can at least compare those two categories over the years; both streams rose in 2024, with commercial activities up £7 million (19 per cent) and retail and merchandising up £3 million (24 per cent).

Little detail here, but from public reports we know the club’s front-of-shirt deal with Betway rose £2 million to £12 million last season, while other sponsorship deals were aided by the visibility offered by European football. Whether a lack of the latter sees a sizeable drop-off in 2024/25 remains to be seen. Separately, the club’s pre-season tour of Australia last season is expected to have boosted the coffers commercial as well.

The greatest income disparity in England right now lies in the commercial field, and West Ham are a perfect example. The Hammers have the seventh-highest commercial income in England, yet it pales in comparison to the Big Six; sixth-place Arsenal’s commercial revenues are nearly triple those of their London rivals. In all, EPL clubs booked £1.96 billion in commercial income at last check.

Returning to our peer comparison, West Ham have generally only trailed Everton commercially in recent years. The Toffees now trail everyone else, in part because their recently chaotic ownership situation was directly driven by lost commercial revenues, though it’s expected that The Friedkin Group will focus on this revenue stream following their takeover last month.

West Ham’s commercial growth is impressive, but it needs to be given what the club’s rivals are doing. Newcastle United’s commercial exploits have been well-documented, as the club’s Saudi Arabian ownership seeks to grow revenues as quickly as they can within, meanwhile Aston Villa’s current Champions League campaign should see a strong increase in this area too.

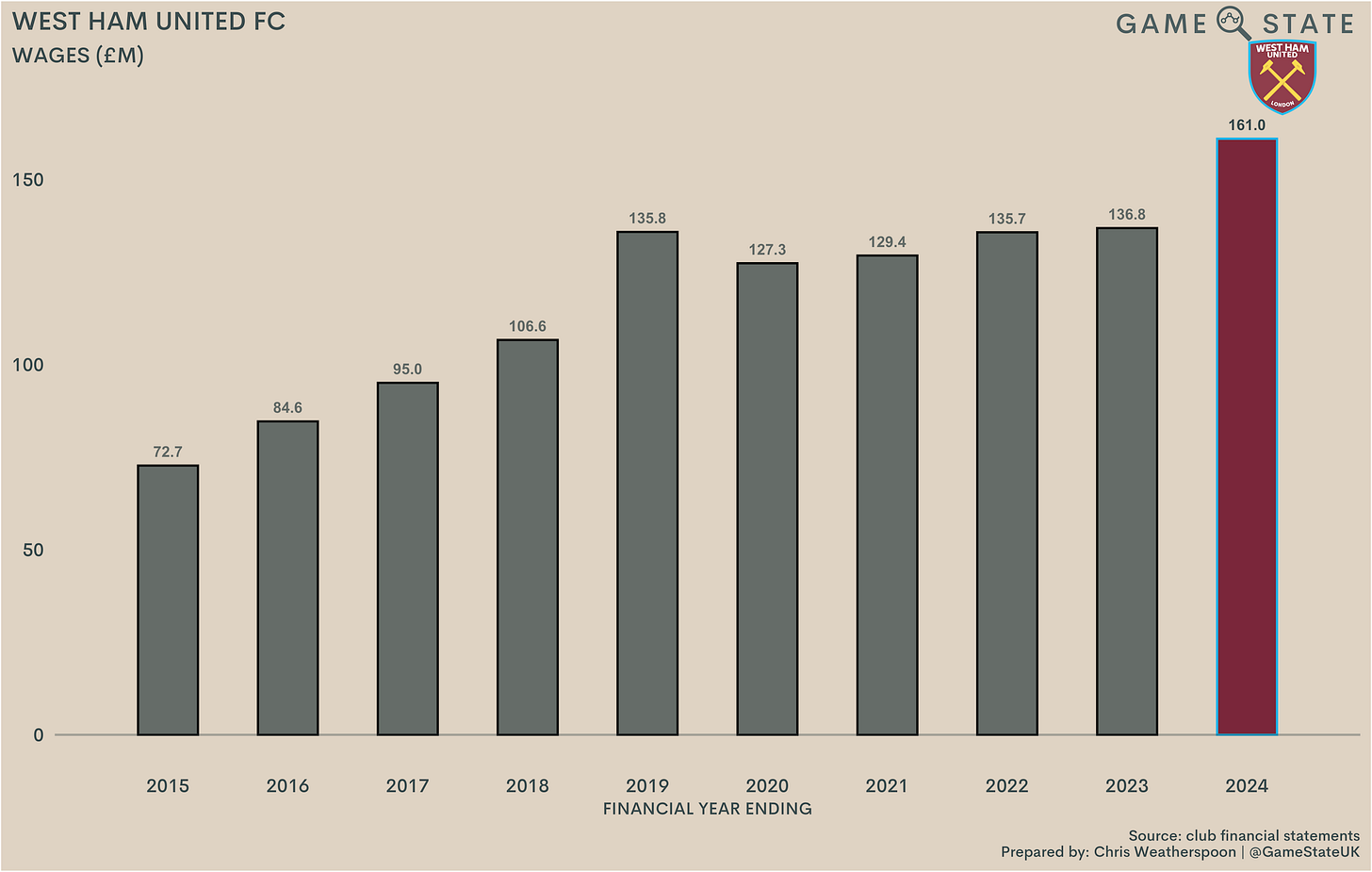

Wages

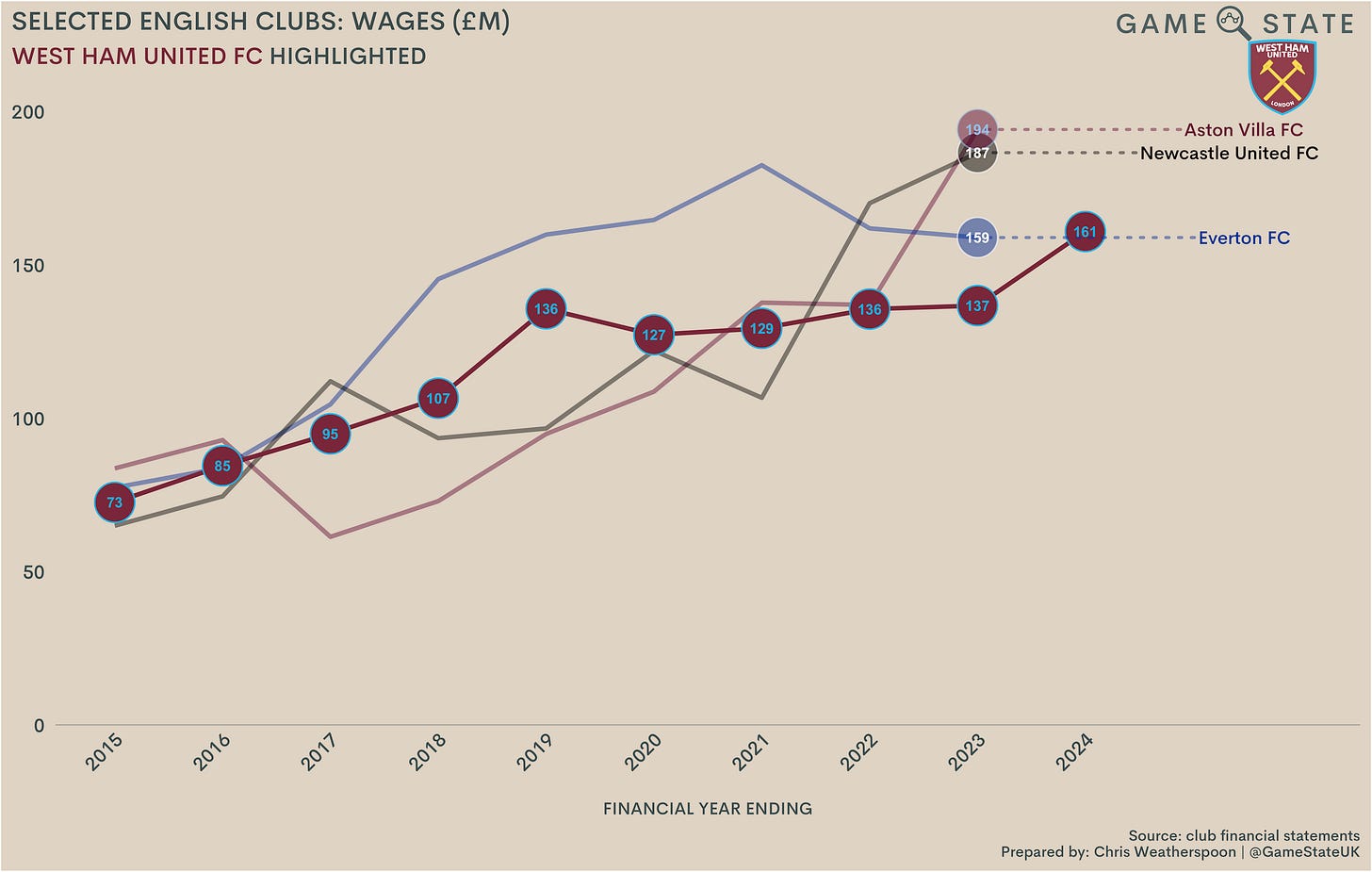

After five years of remaining static, West Ham’s wage bill leapt in 2023/24, up 18 per cent to £161 million. Some of that will relate to bonuses paid for the Conference League success (the club didn’t disclose the quantum of these) but there’ll also have been an increase in the underlying wage bill as a result of transfer activity and contract renewals. Star man Jarrod Bowen, for one, signed a new contract in October 2023 reportedly worth £150,000 per week, a near-tripling of the £55,000 weekly contract he is believed to have signed when joining The Hammers in January 2020.

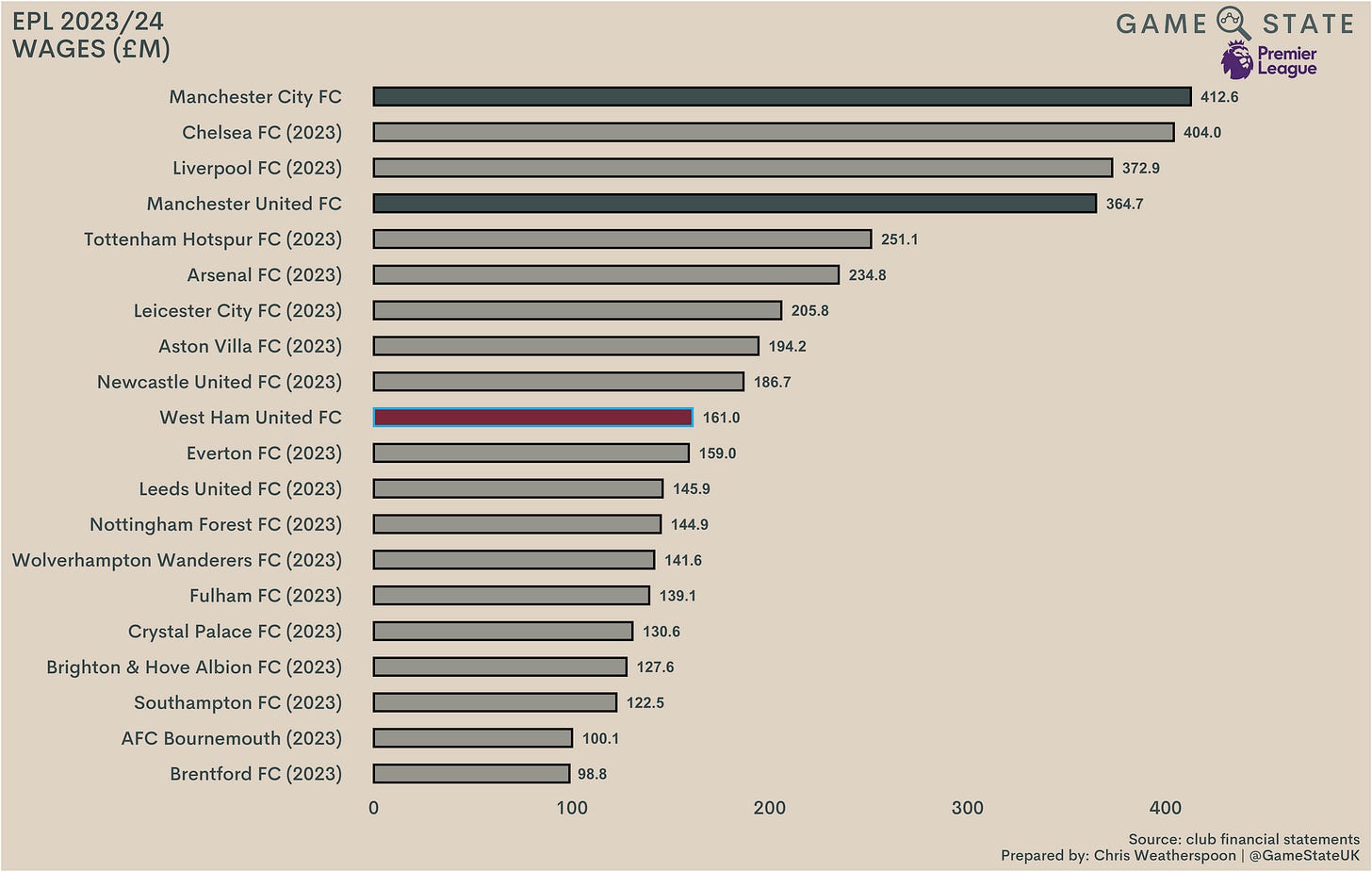

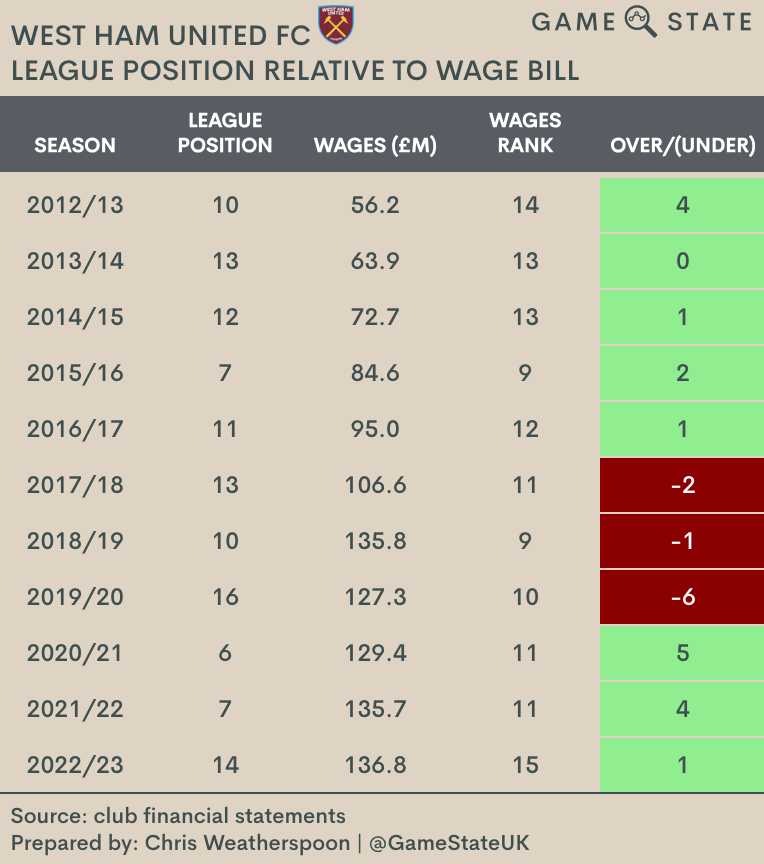

Based on most recent figures, West Ham’s £161 million wage bill was the EPL’s 10th-highest, so finishing ninth in the division last season represents a small over-performance. That said, 17 clubs are yet to publish 2024 figures and wages trend ever upwards, so it’s possible West Ham outperformed their staff costs by more than just one place. The Hammers wage bill in 2023 was then the EPL’s sixth-lowest, as the lack of growth meant several other clubs skipped past them in their staff spending.

In all, the combined most recent wage bills of the 20 EPL clubs totalled £4.1 billion.

Both Newcastle and Aston Villa have overtaken The Hammers in recent years when it comes to wage bills, a theme that won’t have been reversed once all three clubs’ 2024 accounts are published. West Ham’s wage control has generally been admirable, and last season represented another over-performance in that regard, but there’s a reason wage bills generally correlate with on-pitch performance. If peer wage bills continue to surge ahead, West Ham will struggle to keep up.

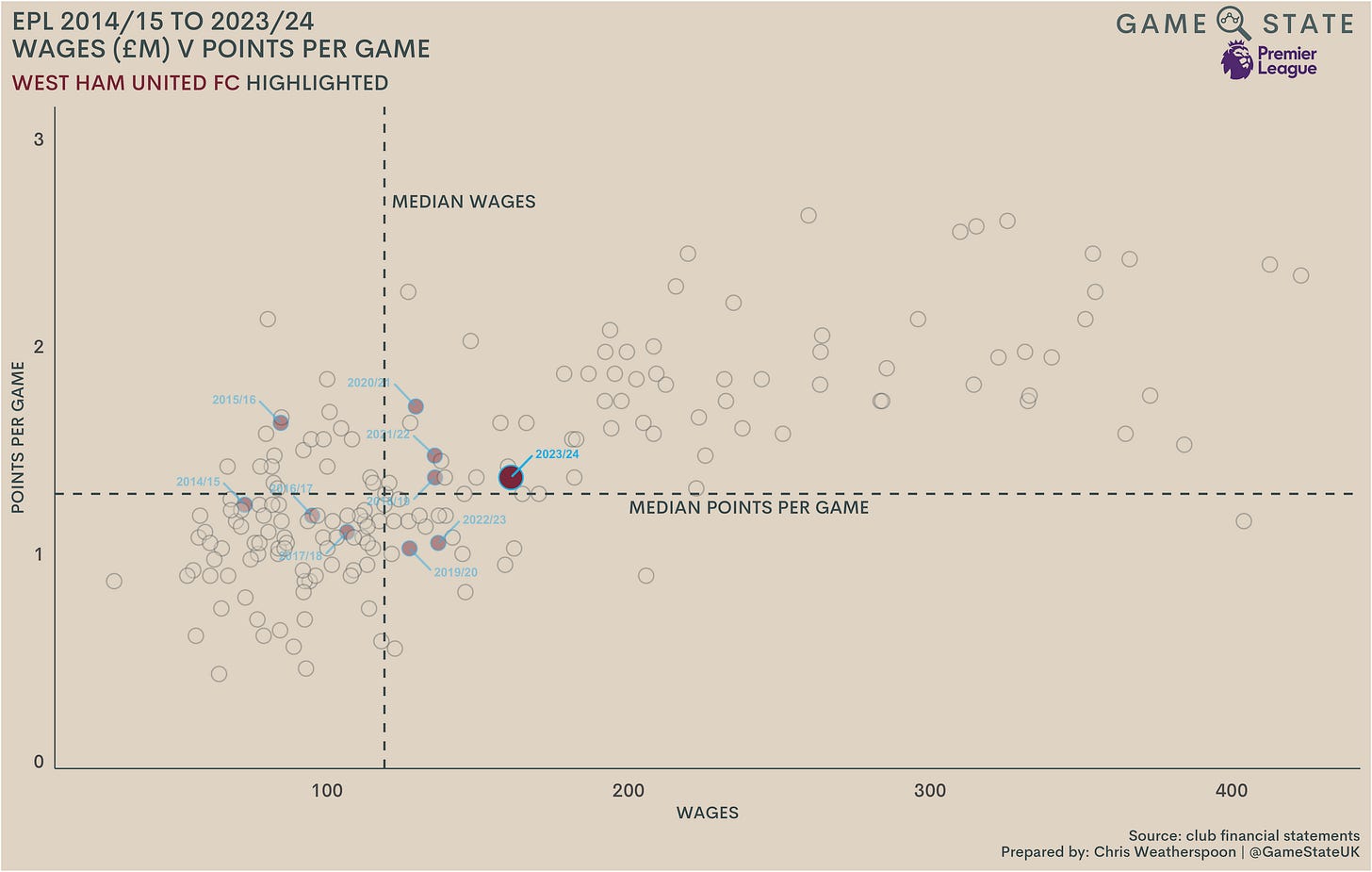

Plotting The Hammers’ wages against their league performance - denoted by points generated per game - shows both the increase in the club’s wage bill last season and their recent ability to generate more than the median points total of the division. Last season, as mentioned, was an over-performance, though less so than 2021’s sixth-placed finish, achieved with only the 11th-highest wage bill in the division.

Aside from a blip in the late 2010s, the Hammers have generally performed to or better than their wage bill across the last 12 seasons (insufficient teams have published wage data to allow for a 2023/24 assessment):

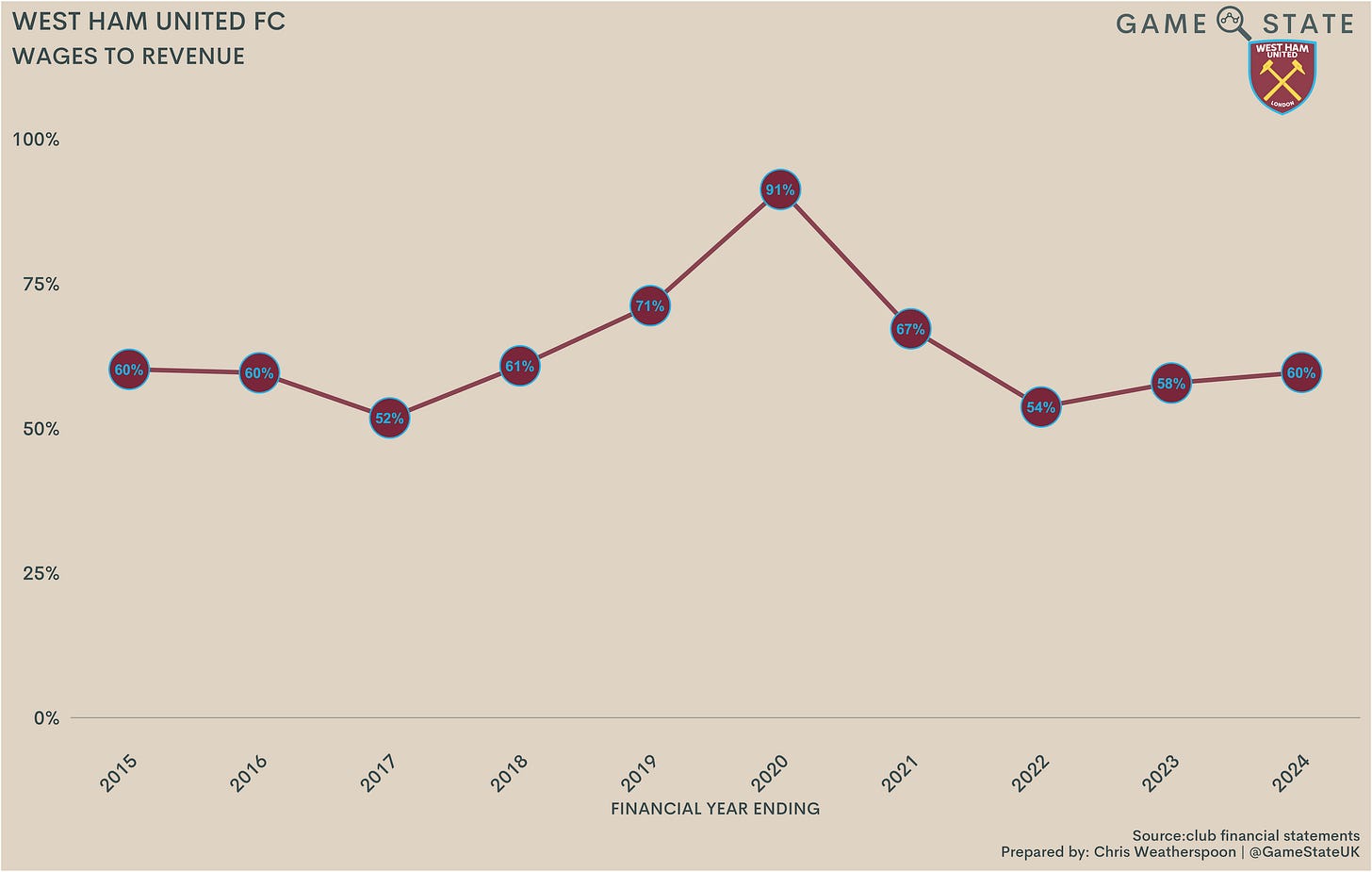

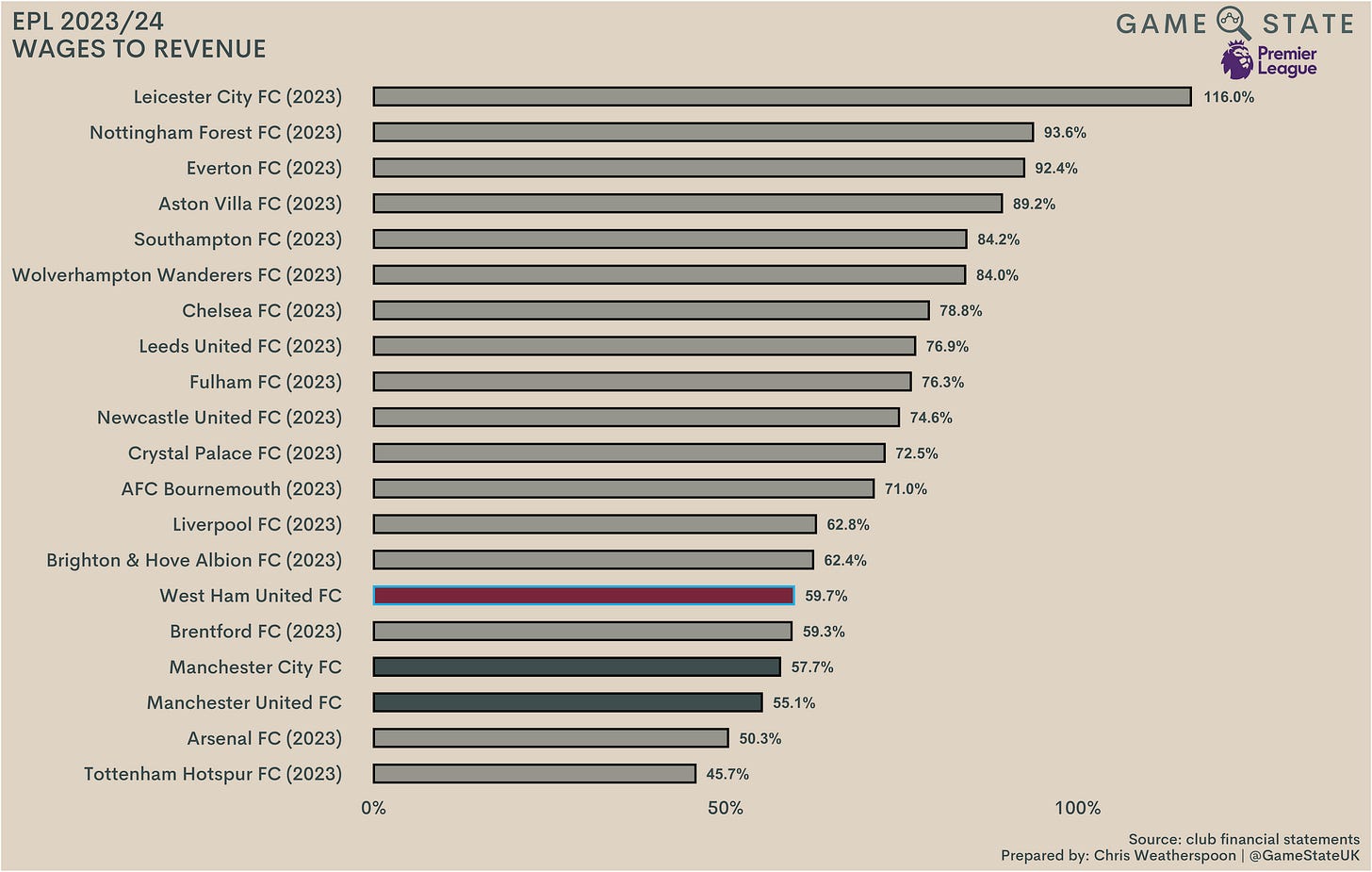

Save for a Covid-induced blip that all clubs suffered from, West Ham’s wage control has been strong across the last decade. While it rose a tad last year, the club’s wages to revenue metric sat at a healthy 60 per cent, and assessed across the last 10 years it sat at an average of 62 per cent.

That pitches The Hammers firmly at the lower (i.e. better) end of the EPL scale, with only six clubs displaying a better wages to income percentage. Those at the top end of this chart correlate pretty well with those clubs who’ve experienced PSR issues in recent seasons, which is unsurprising given wages continue to make up a club’s highest cost.

West Ham have managed to keep wages in check even as revenues have risen, though this is an area to keep eye on when the 2025 accounts land. It is unknown how much the club paid in bonuses for that Conference League success, but our estimated £24 million drop in income from European competition will be difficult to offset with wage cuts and will require other revenue streams to be improved.

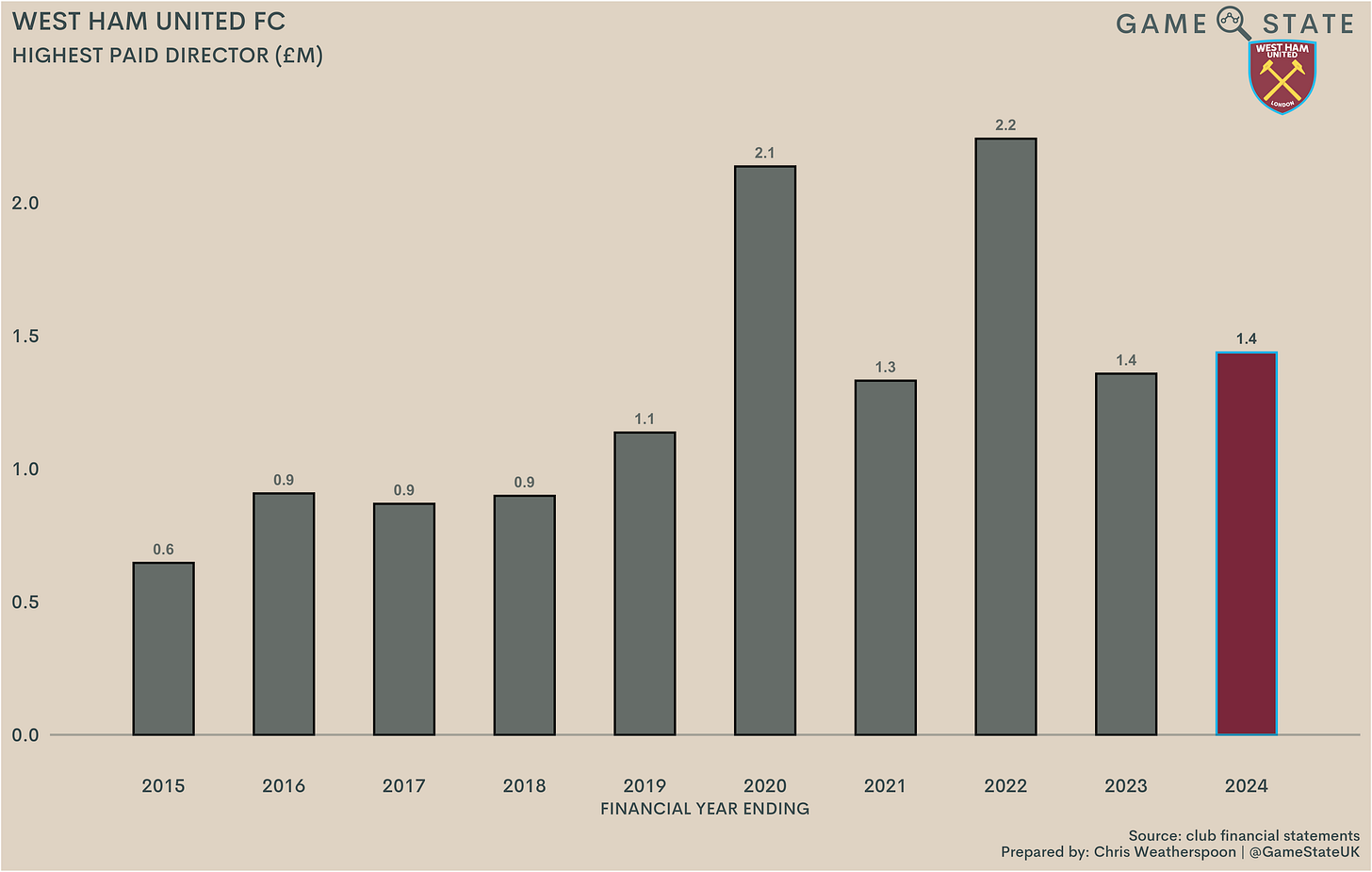

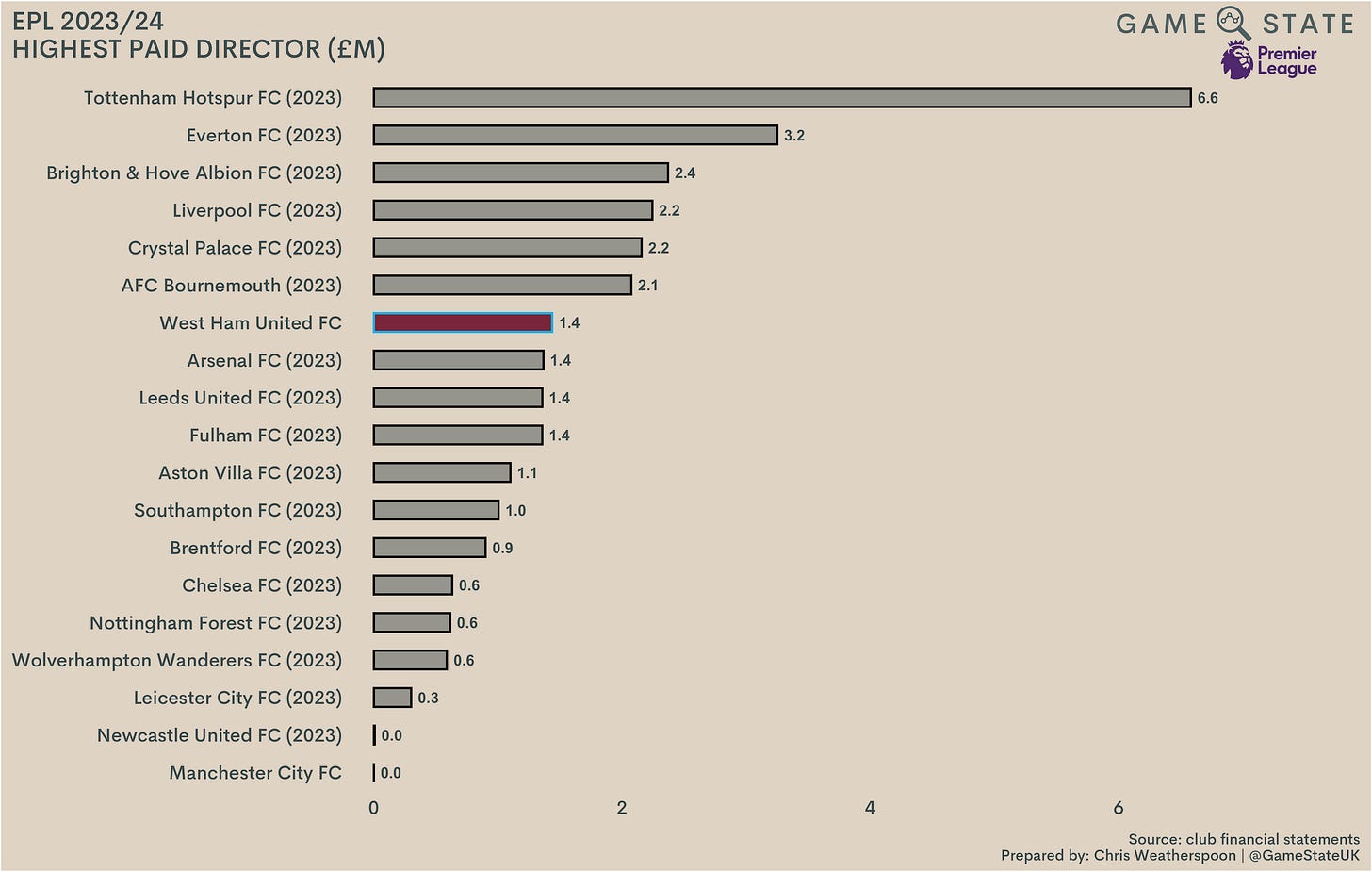

As a slight aside but related to wages, West Ham’s highest paid director was paid six per cent more than in 2023, seeing their salary rise from £1.357 million to £1.437 million. Though not confirmed in the accounts, this is widely assumed to be the salary of Karren Brady, who has held the post of West Ham’s Vice-Chairman since January 2010. The combined amounts that went to the highest paid director in each year since then are now at £16 million, though it’s unclear if Brady has met that definition in each of those years.

Whomever it is, West Ham’s highest paid director earned more than directors at 12 other EPL clubs at last check (note: Manchester United do not disclose this figure).

Other expenses

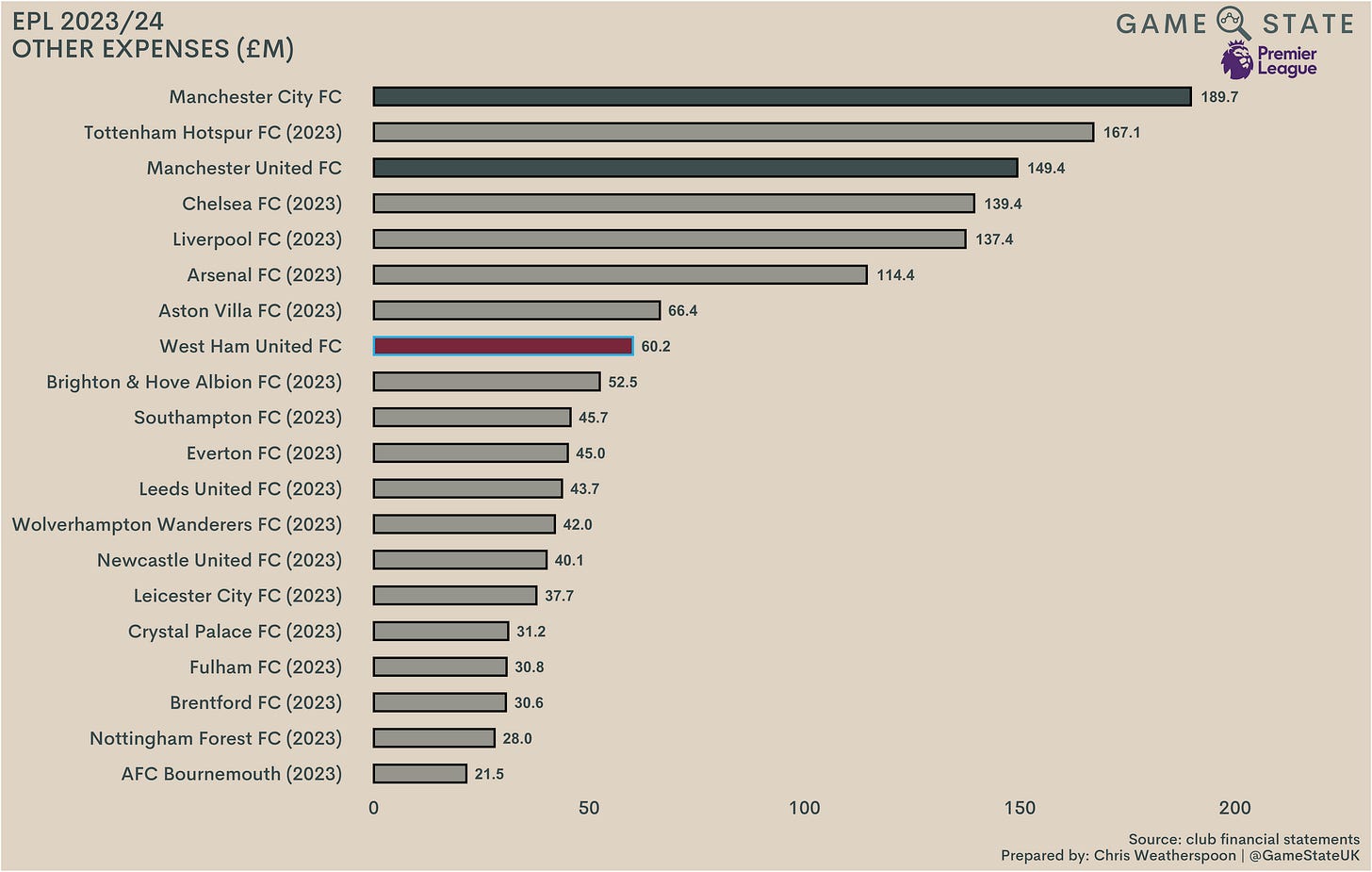

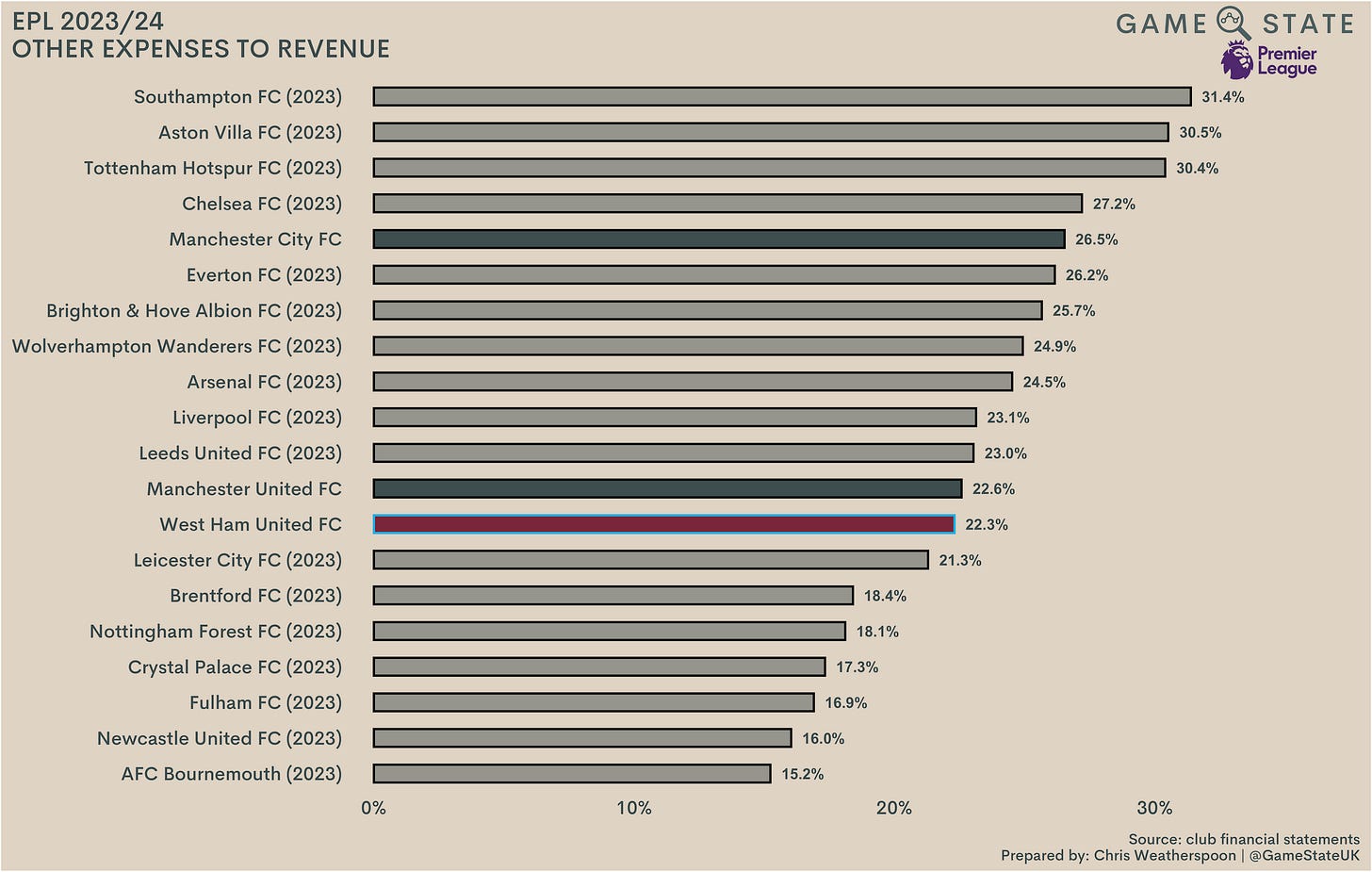

Another club record landed in the form of West Ham’s other, or non-staff, expenses. These shot up, rising £13 million and 27 per cent to £60 million, double what they were in 2017. A lot of clubs have seen non-staff expenditure rise in recent years given the general inflationary environment, but even in relative terms it’s a big uptick; Manchesters United and City, the only other two EPL clubs to publish 2024 financials, only saw a 7-8 per cent rise in this cost category.

Like many clubs, The Hammers don’t provide much in the way of detailed breakdowns of non-staff costs. It’s difficult to pinpoint the driver behind the rise, though the increased costs incurred by extra games in Europe and travelling much further in pre-season (the club played two games in Australia last year, having ventured no farther than Italy in 2022) will have had an impact. Other increases likely lie in the costs of increasing that commercial income so impressively.

West Ham had the eighth-highest other expenses in the EPL, trailing the usual six and Aston Villa. Obviously the club would like to keep these costs down, but it’s a fact of life that clubs with big stadia will incur big costs. In fact, West Ham’s could (some might say should) be a lot larger; the club, as tenants rather than owners of the London Stadium, don’t have to cover the sizeable maintenance costs like their rivals do. Nor do they have to pay for heating or cleaning or, in one of those football-specific quirks that seems equally funny and ridiculous, goal posts or corner flags.

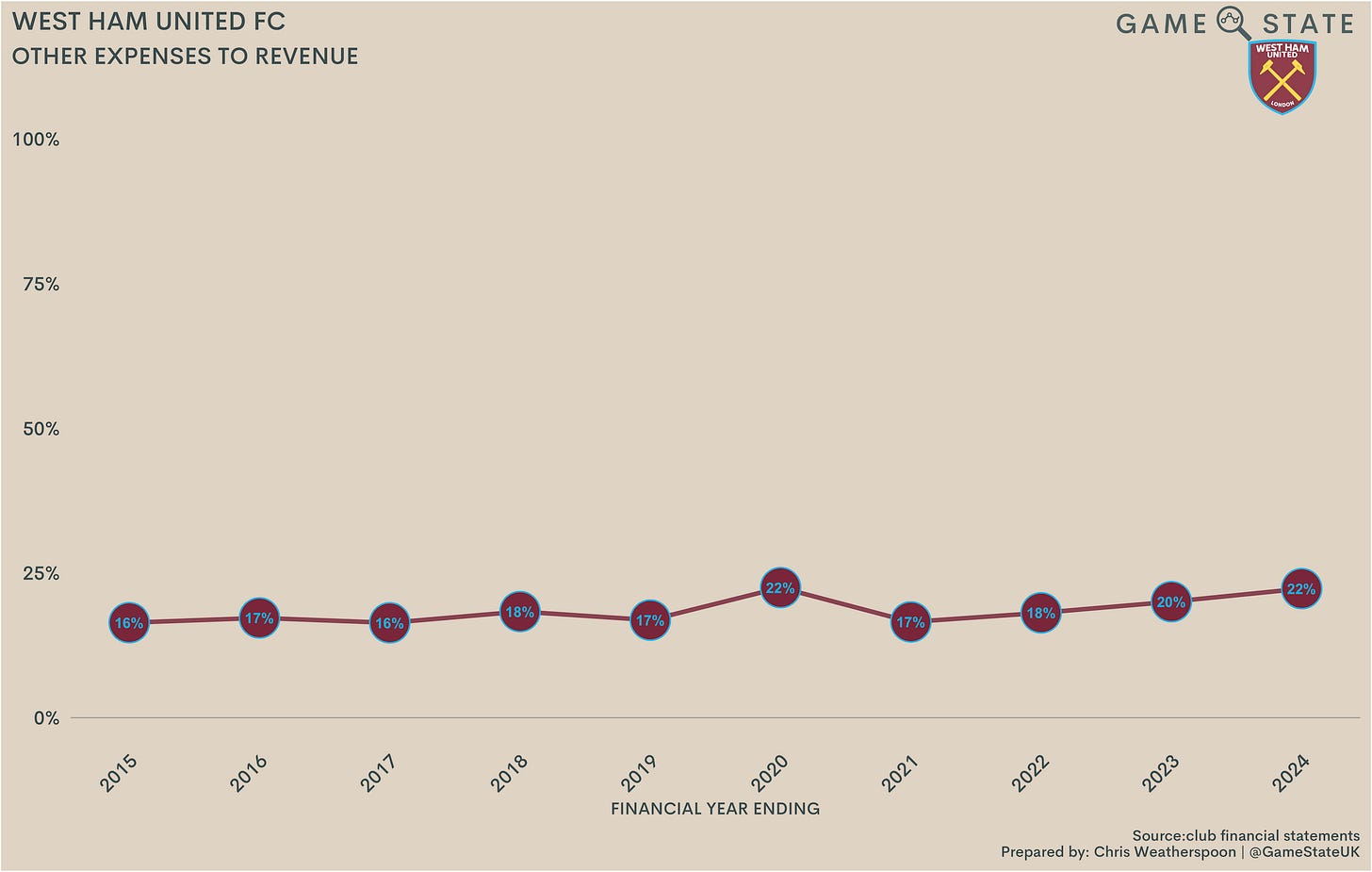

Thought West Ham’s other expenses jumped, they only slightly outstripped revenue growth. These costs comprised 22 per cent of income (2023: 20 per cent), and while that’s the joint-highest for the club in the last decade there’s been little in the way of drastic movement here. That being said, with income potentially dropping this season, these costs may start to bite more.

That 22 per cent figure is in the lower half of the EPL, with seven clubs spending a lower proportion of their income on non-staff costs (excluding fixed asset depreciation).

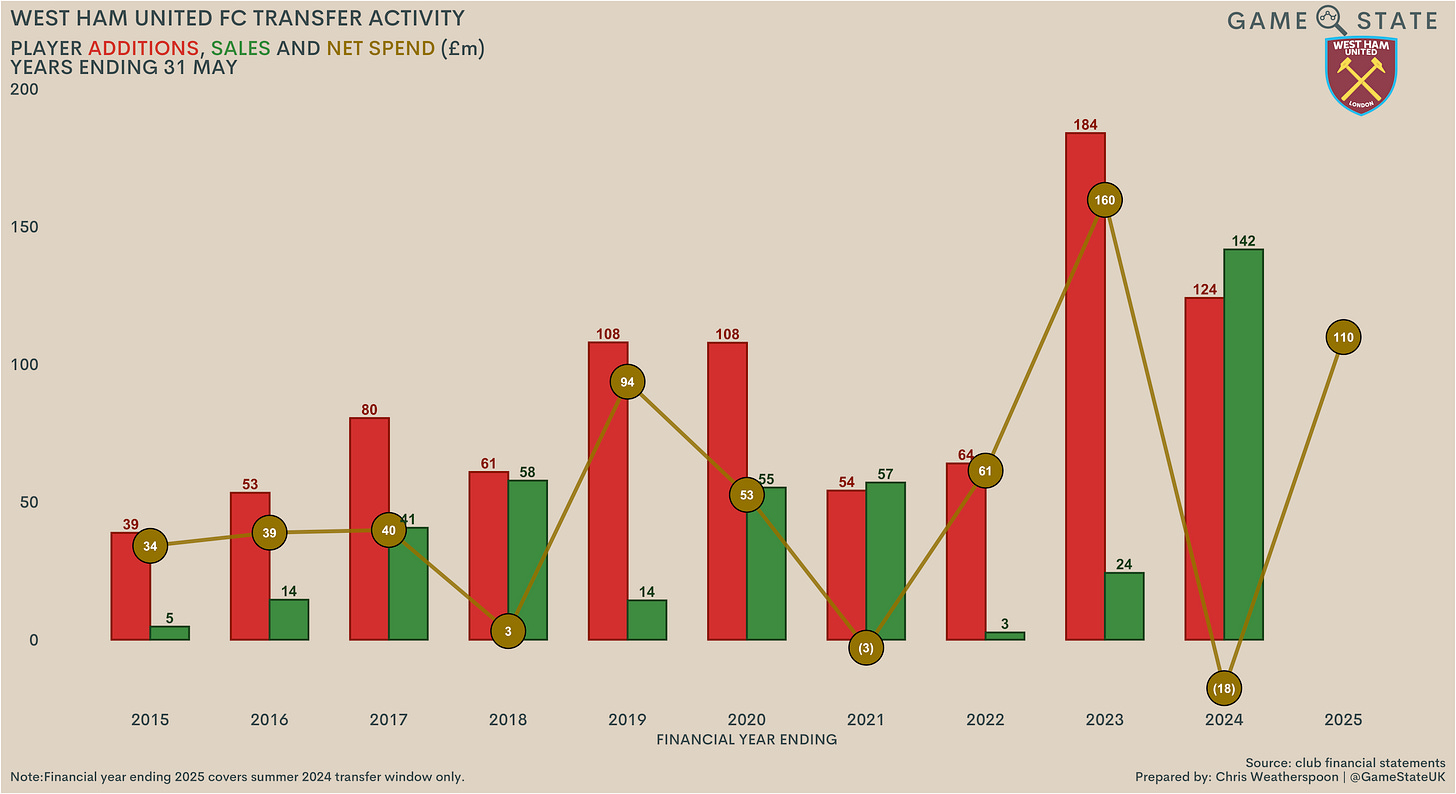

Player trading

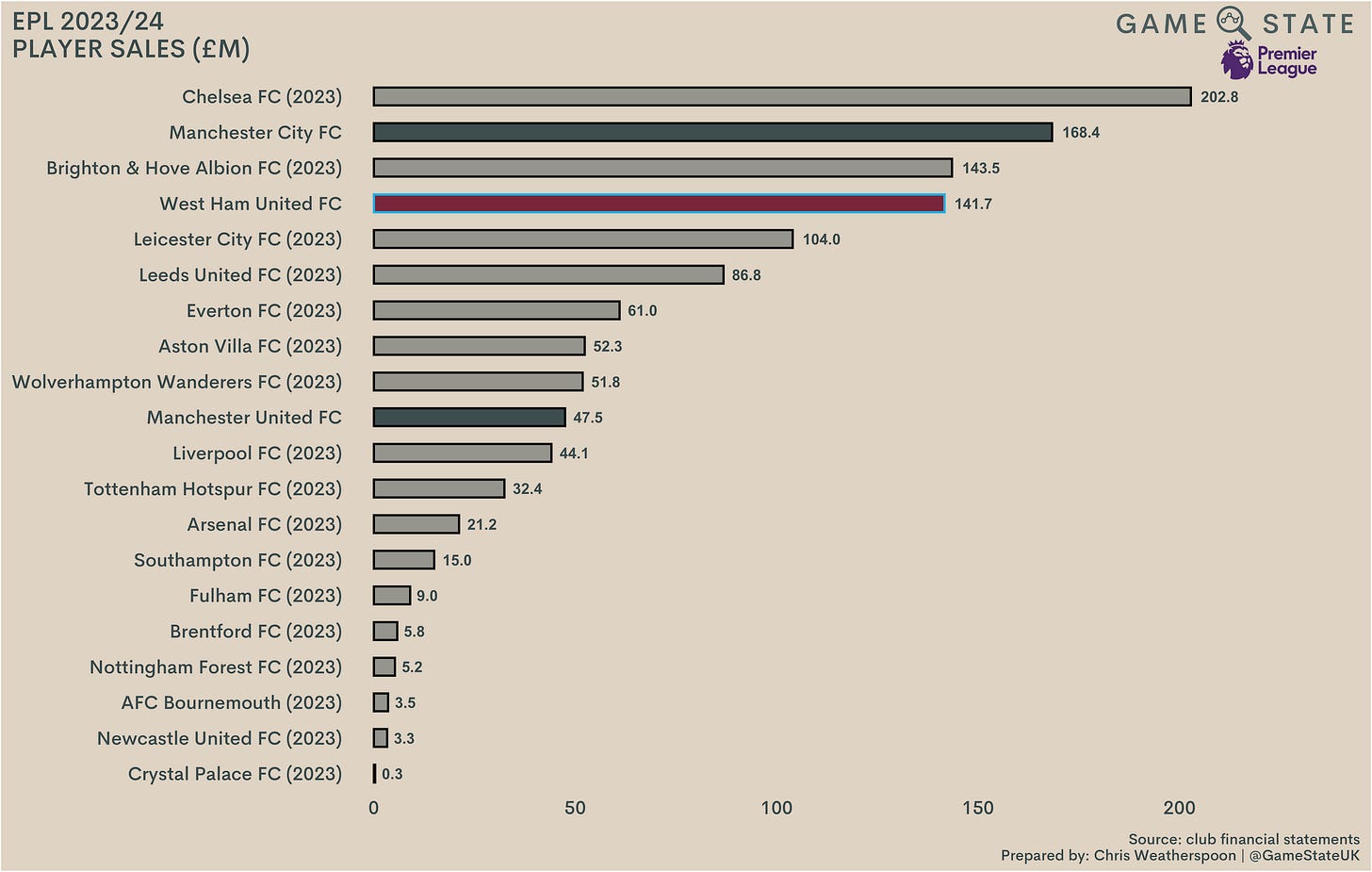

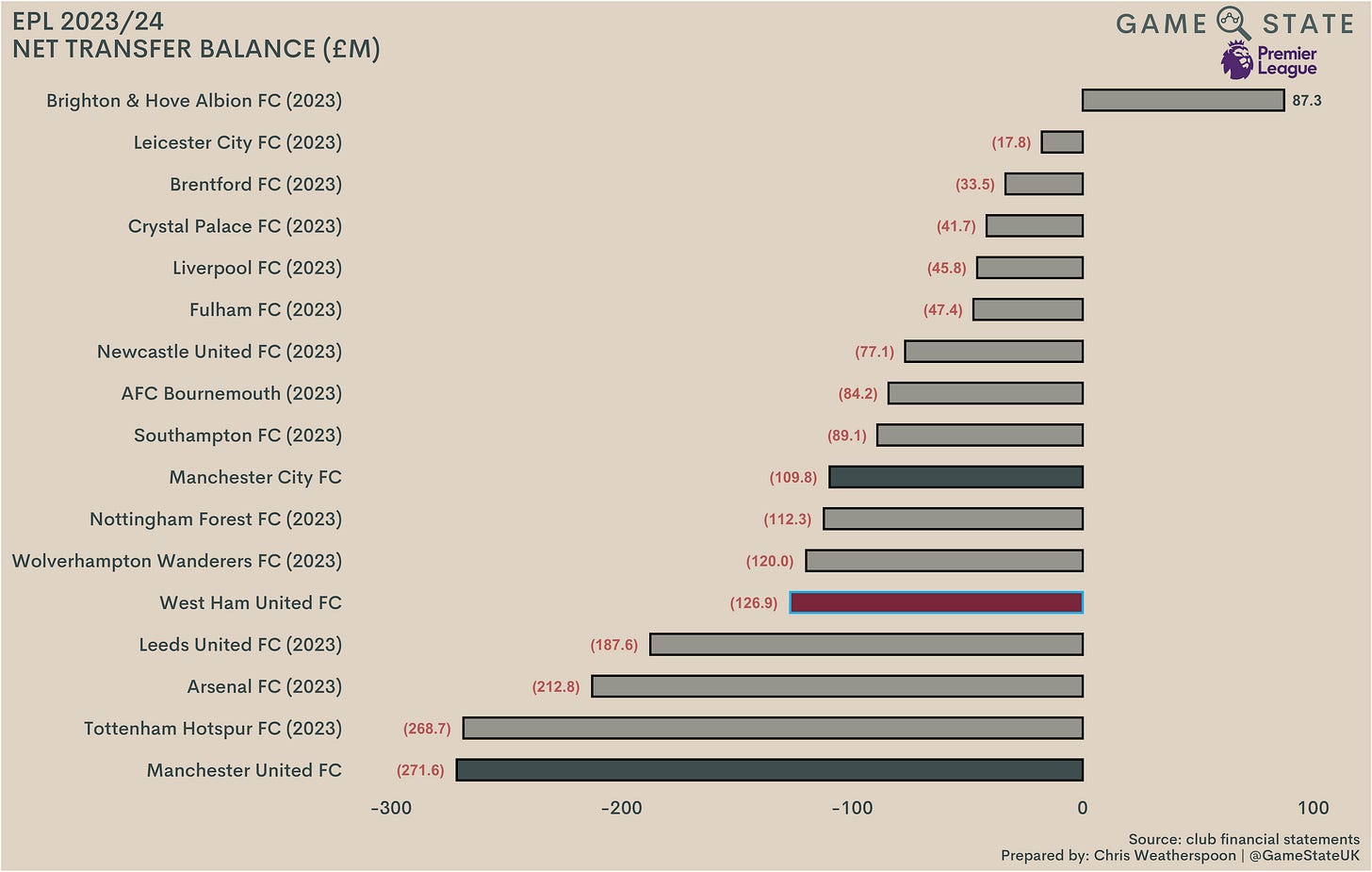

Declan Rice’s bumper sale ensured West Ham’s net transfer spend was negative for only the second time in 10 years, as the club’s £142 million in player sales outstripped £124 million spent on new additions. That marked a significant shift from the £160 million net spend in 2023, though since 2015 the club has still spent far more than it has received in the transfer market. In that span, The Hammer’s net spend totals £463 million, split £875 million purchases and £413 million sales.

Expanding our scope to include the most recent summer transfer window sees that figure soar over the half-billion pound mark. West Ham’s accounts didn’t break down the split of additions and sales for the summer of 2024, but they did confirm the club spent a net £110 million on attempting to better the existing playing squad.

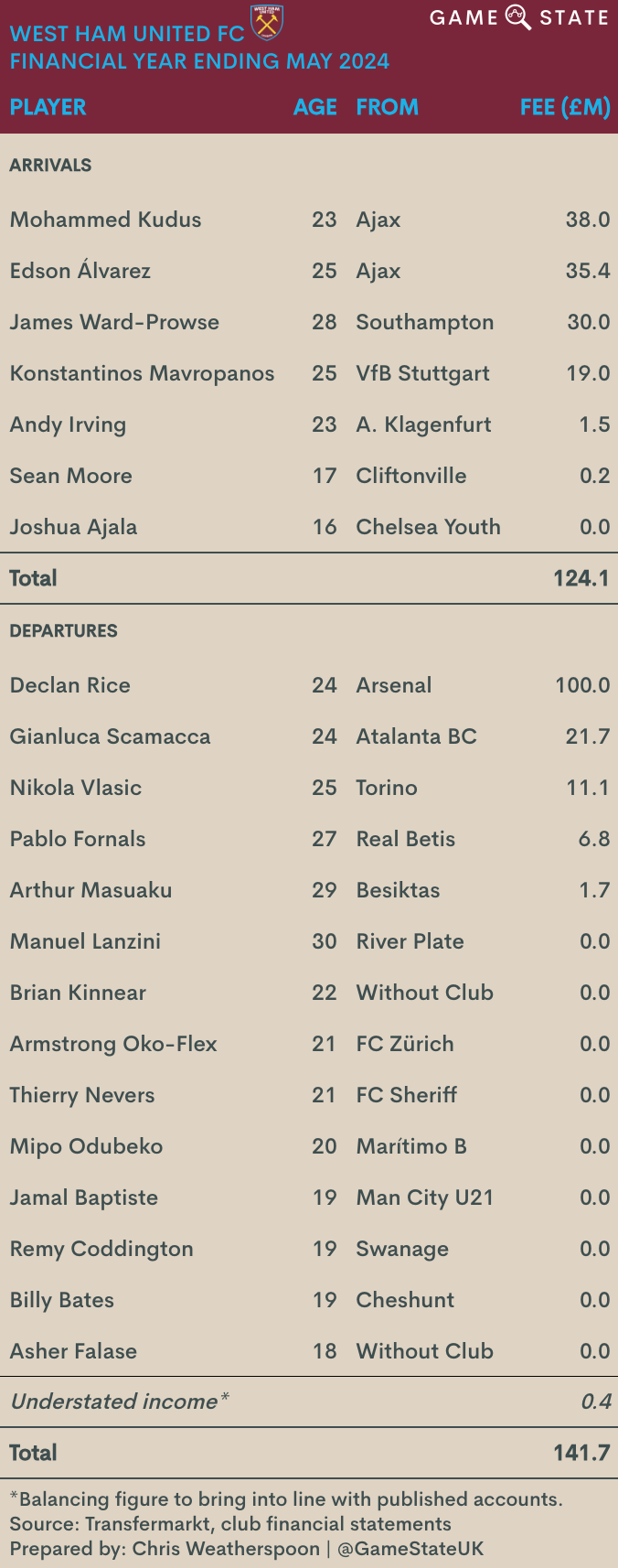

Reverting to 2023/24, The Hammers spent eight-figure sums on four new players: Mohammed Kudus, Edson Álvarez, James Ward-Prowse and Dinos Mavropanos. Ajax were the biggest beneficiaries of West Ham’s spending, receiving over £73 million in exchange for Kudus and Álvarez.

Going the other way, Rice’s £100 million move obviously stole the headlines but West Ham did still generate a further £42 million on top. That stemmed from the sales of Gianluca Scamacca (£22 million) and Nikola Vlasic (£11m) and the conversion of Pablo Fornals loan move to Real Betis into a permanent one (£7 million).

Scamacca had only been bought from Sassuolo a year earlier for £31 million, so his return to Serie A with Atalanta for just £22 million represented a loss both in fee terms and accounting terms. We estimate that West Ham booked a loss on sale of £3 million on Scamacca, which helps to explain why the club’s total profit on player sales in 2024 was £96 million when Rice, an academy player with negligible book value, was sold for more than that.

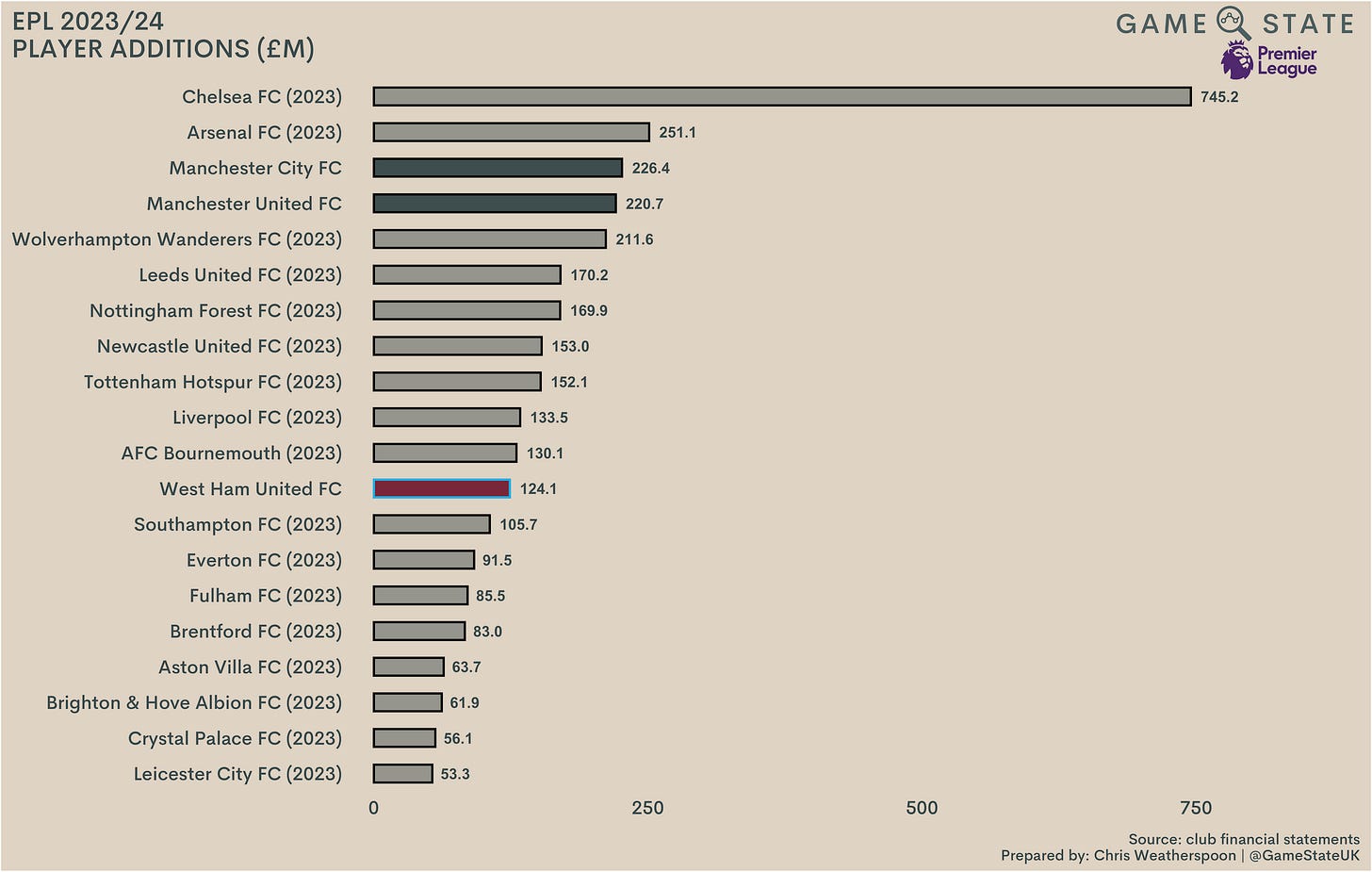

Despite shelling out over £100 million on new players, the hive of activity that is the EPL transfer market meant West Ham are in the bottom half for most recent annual transfer fees spent. Thirteen different clubs spent over £100 million on new signings, and five over those went over the £200 million barrier (and, among those, Chelsea went some way further than that). Taking just the year of clubs’ most recently published financials, the 20 EPL clubs spent an astonishing £3.3 billion on new players.

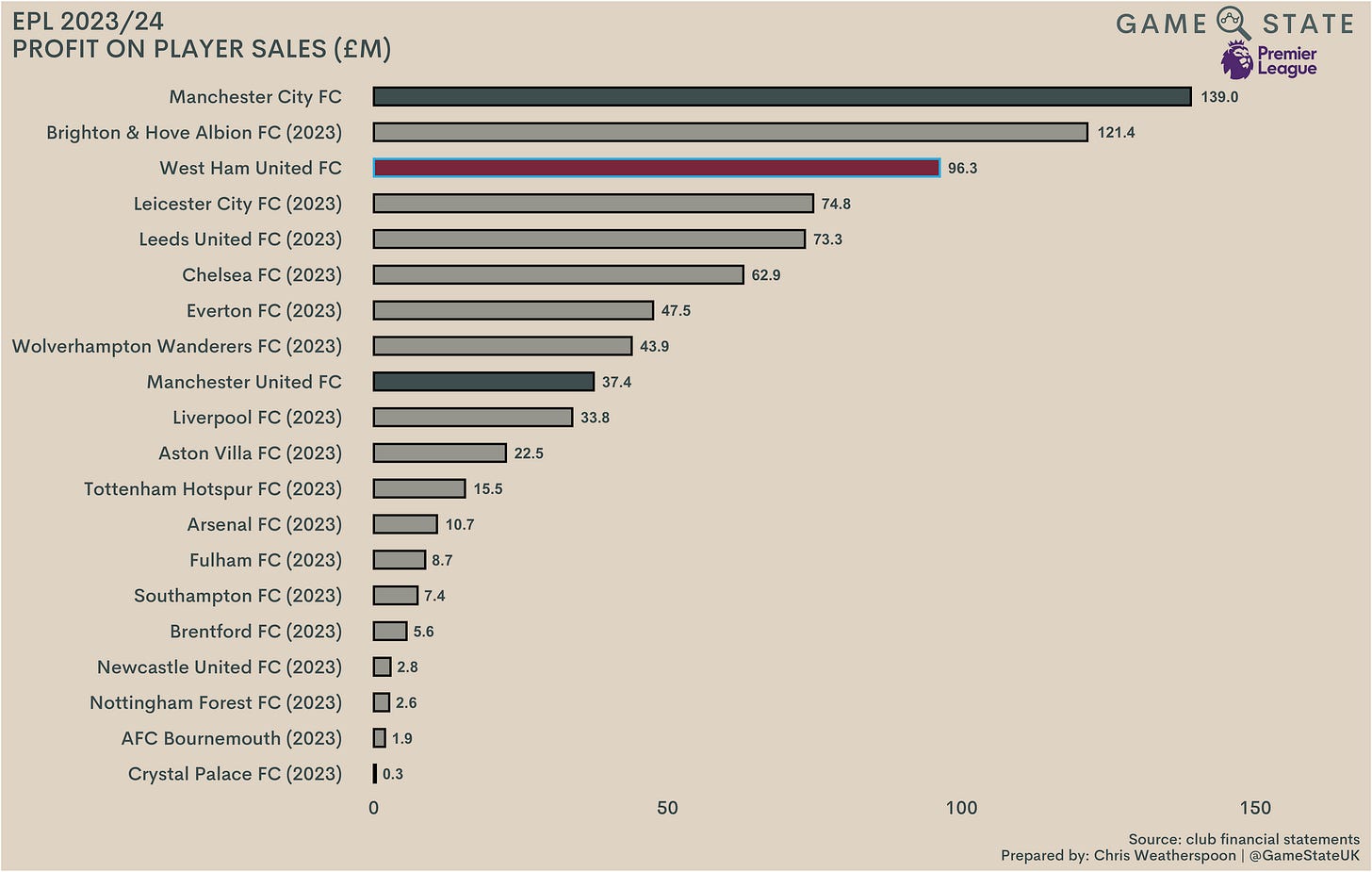

While many clubs show signs of leaning more heavily on a player trading model, the amount they collective generate from sales pales in comparison to the purchase sum. £1.2 billion was generated in fees on departing players, and West Ham sit fourth in this particular ranking, only being out-sold by Chelsea, Manchester City and Brighton & Hove Albion. Of course, much of The Hammers’ £142 million in sales was attributable to the Rice sale. Without that, they’d sit firmly in mid-table.

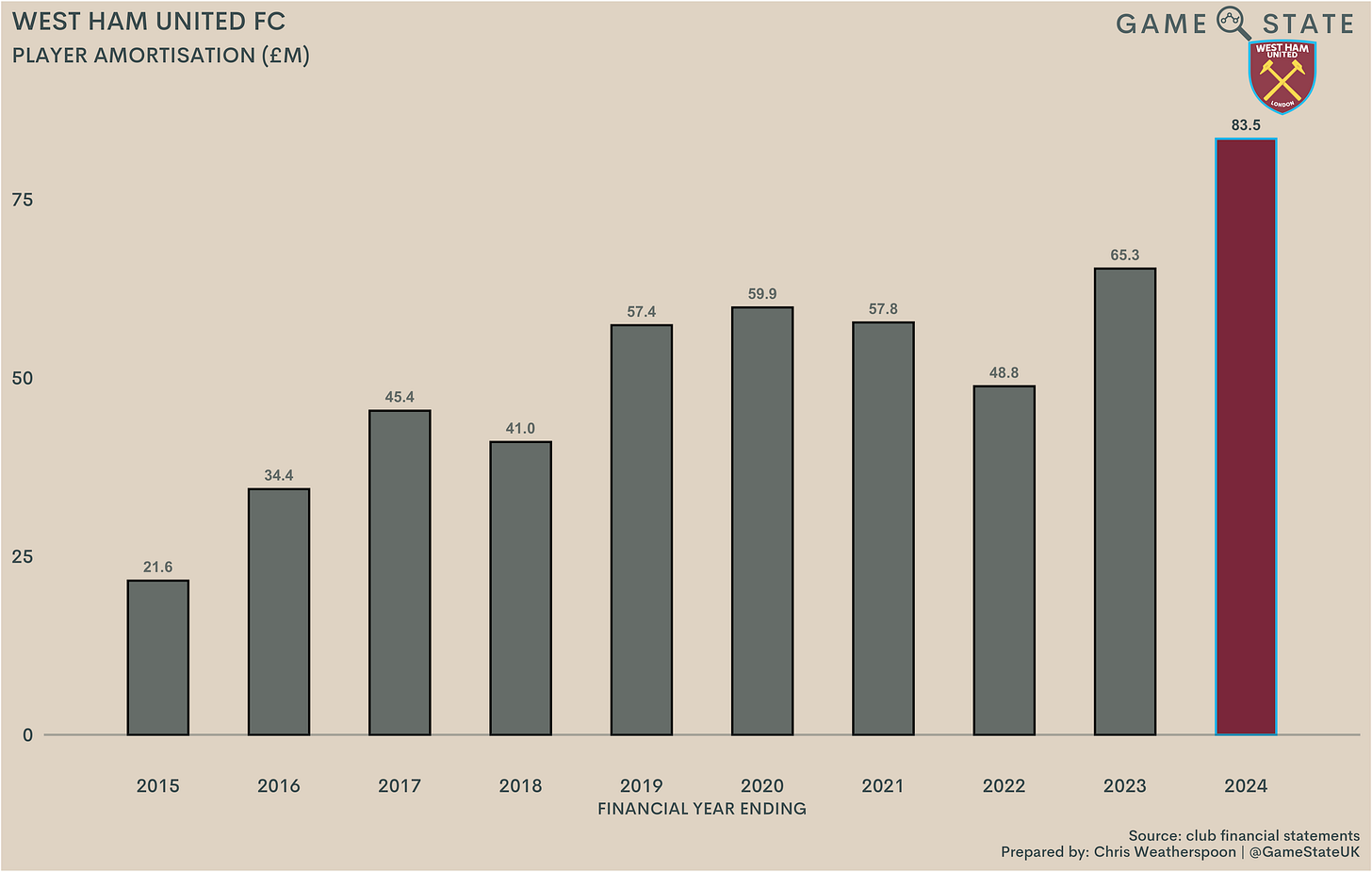

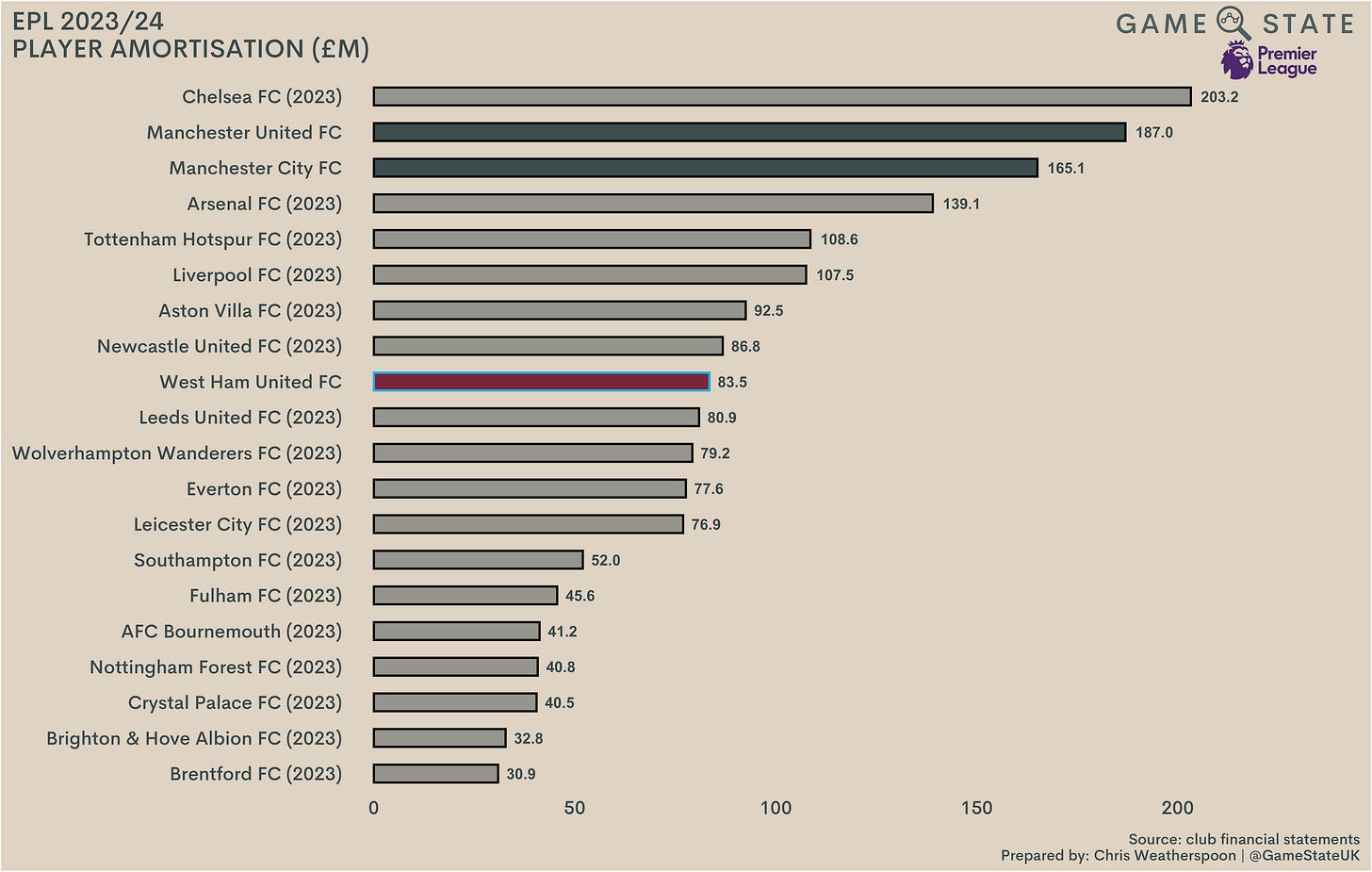

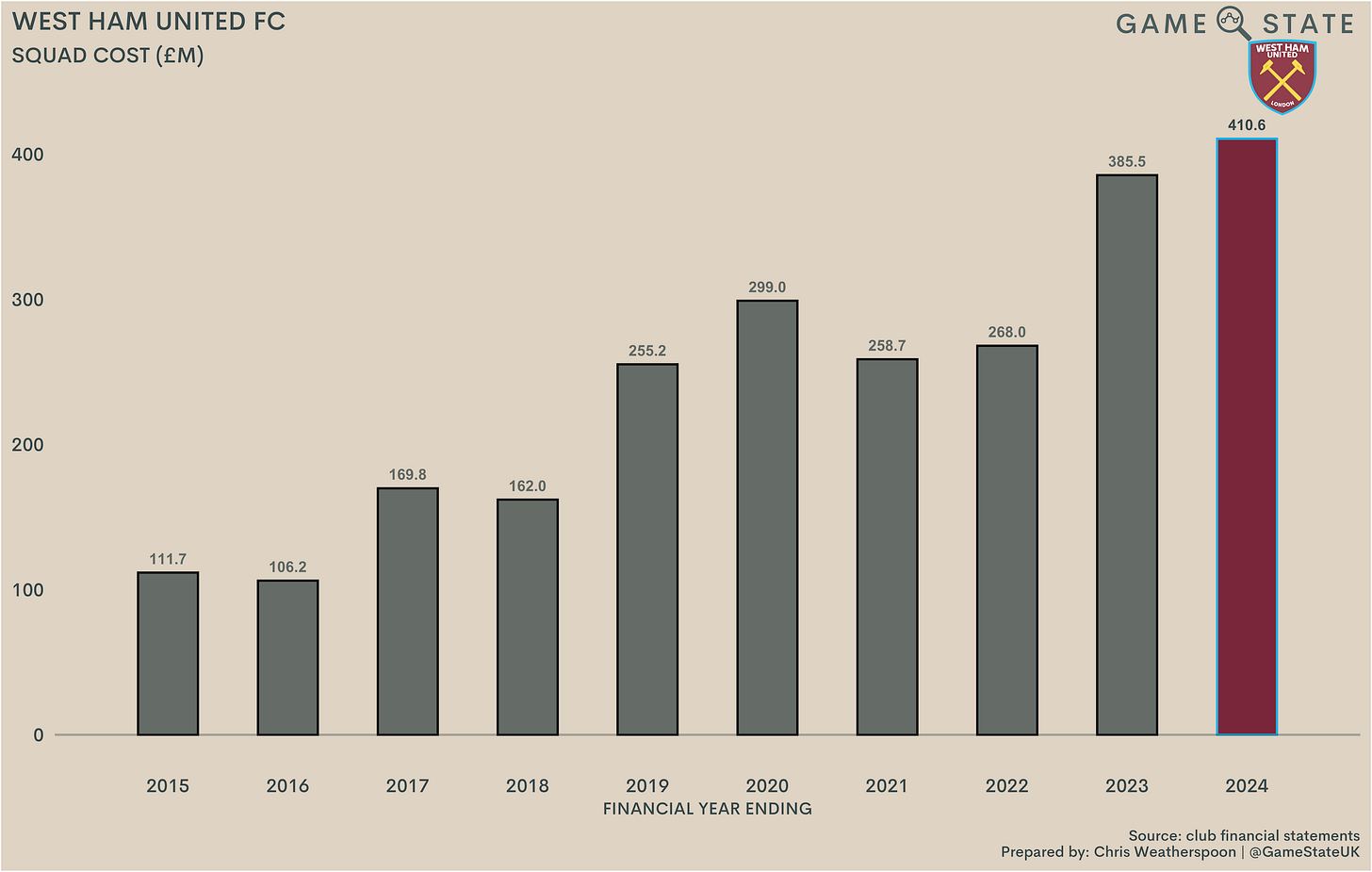

With hefty transfer spending comes hefty player amortisation costs, with those transfer fees being expensed over the lifetimes of players’ contracts. West Ham’s leap to a club record £84 million player expenditure isn’t exactly a surprise given the club spent a combined £308 million on new players in 2023 and 2024.

That’s the ninth-highest player amortisation figure in the EPL currently, and while West Ham are one of a number of clubs rapidly closing in on the £100 million mark, it’s currently only the Big Six clubs who surpass the latter. It’s notable here that the next three clubs are Villa, Newcastle and The Hammers as, at least before this season, those three were generally held up as being in the group of teams seeking to muscle their way into the EPL’s upper reaches.

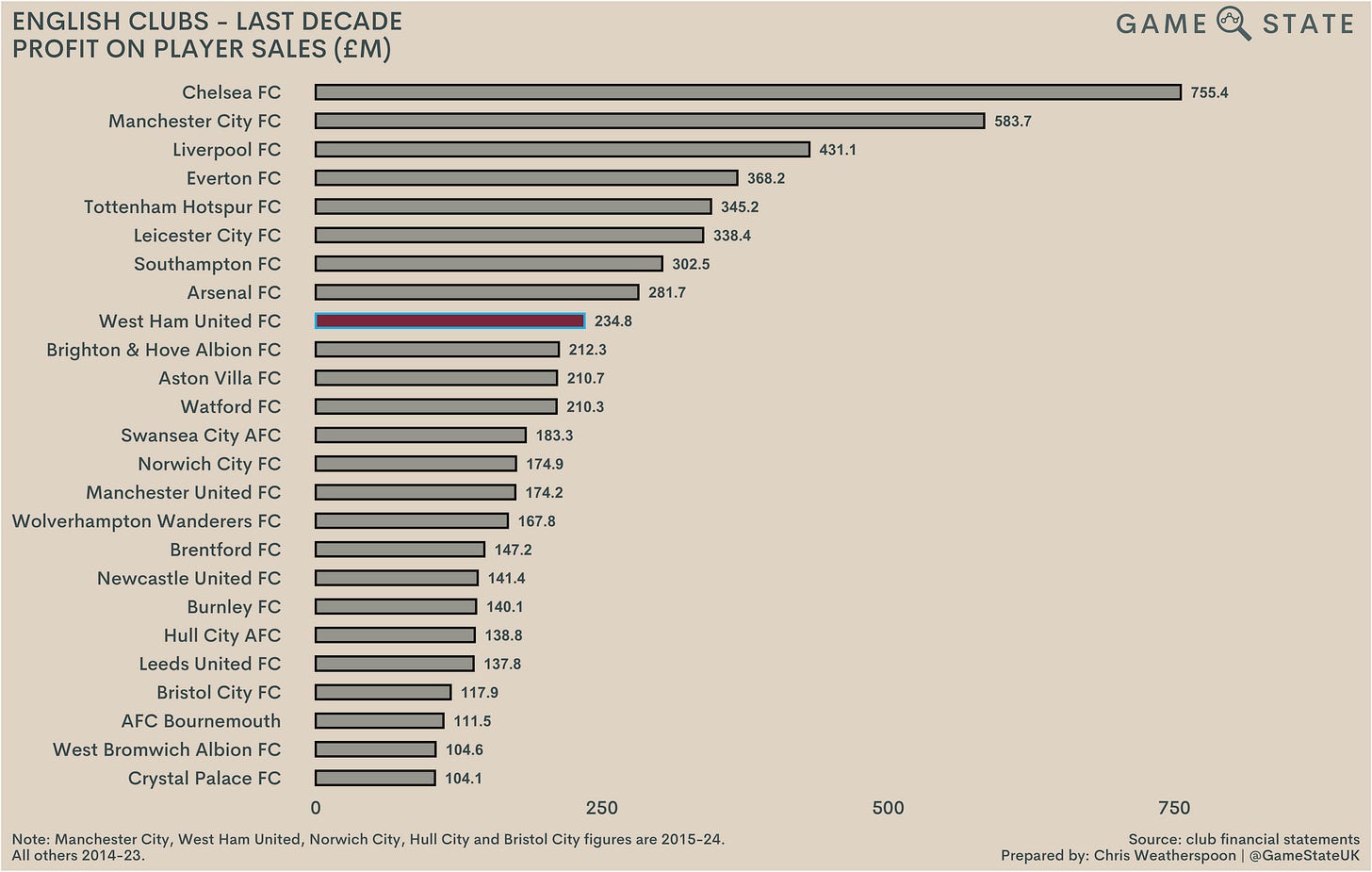

West Ham’s £96 million profit on player sales wasn’t just a club record, it was a huge one, more than tripling the previous high of £30 million in 2018. In the last decade the club has generated £235 million in profit in this way, so the £100 million earned on Rice accounts for roughly 43 per cent of the entire total. Rice’s sale was clearly a one-off and it seems unlikely The Hammers will be shifting to a player trading model any time soon, especially given the hefty net spend seen in the summer just gone.

Outlier or otherwise, West Ham’s £96 million player sale profits were the third-highest in the EPL at latest check, in a division where the combined profit on player sales sat at £808 million. It remains to be seen where The Hammers will sit once all 2024 club financials are published - especially as several clubs engaged in some interesting swap deals last summer in order to boost their PSR loss figures.

Despite the Rice sale being out of step with West Ham’s recent transfer activity, The Hammers have still generated the ninth-most in player profits of any English club over the last decade. Without the Rice sale they’d be 21st in the country, but to suggest that’s a more reliable place for them is unfair. After all, West Ham trained and improved the England midfielder; a hefty transfer fee upon his departure was their just reward. Whether they can mirror the success with future academy stars remains to be seen.

Squad cost

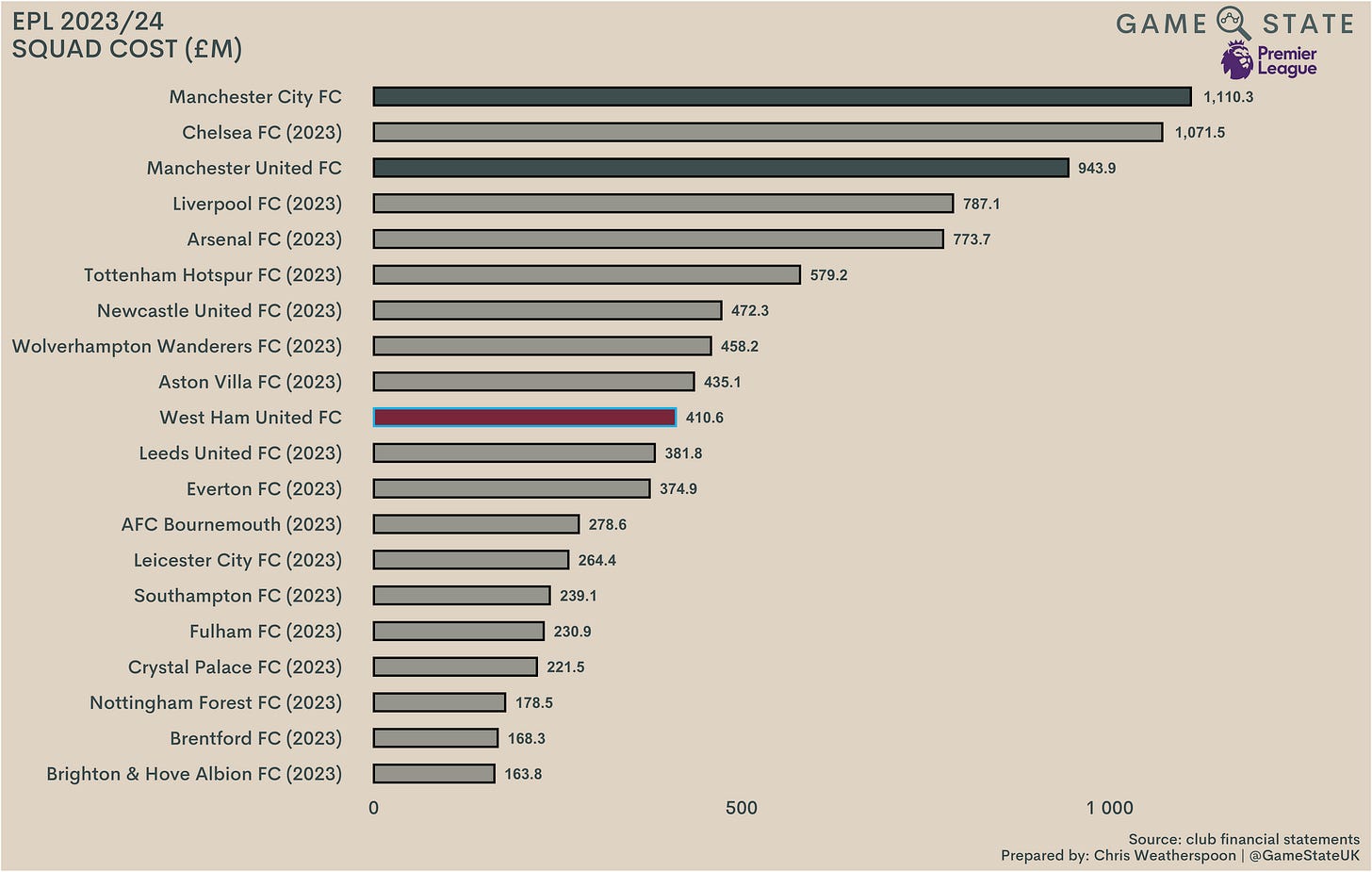

The outcome of West Ham’s transfer activity to the end of May 2024 was a squad that cost £411 million to assemble, another club record. The Hammers’ squad cost has soared in recent years, rising £152 million (59 per cent) since 2021.

Despite that, The Hammers’ squad was only the 10th-most costly in the EPL - and it’s worth remembering here the figures for seven of the clubs above them are now a year out of date. In total, using most recent figures, the 20 EPL clubs have amassed squads costing a combined £9.5 billion. Which is quite a lot of money.

Balance sheet

Football debt

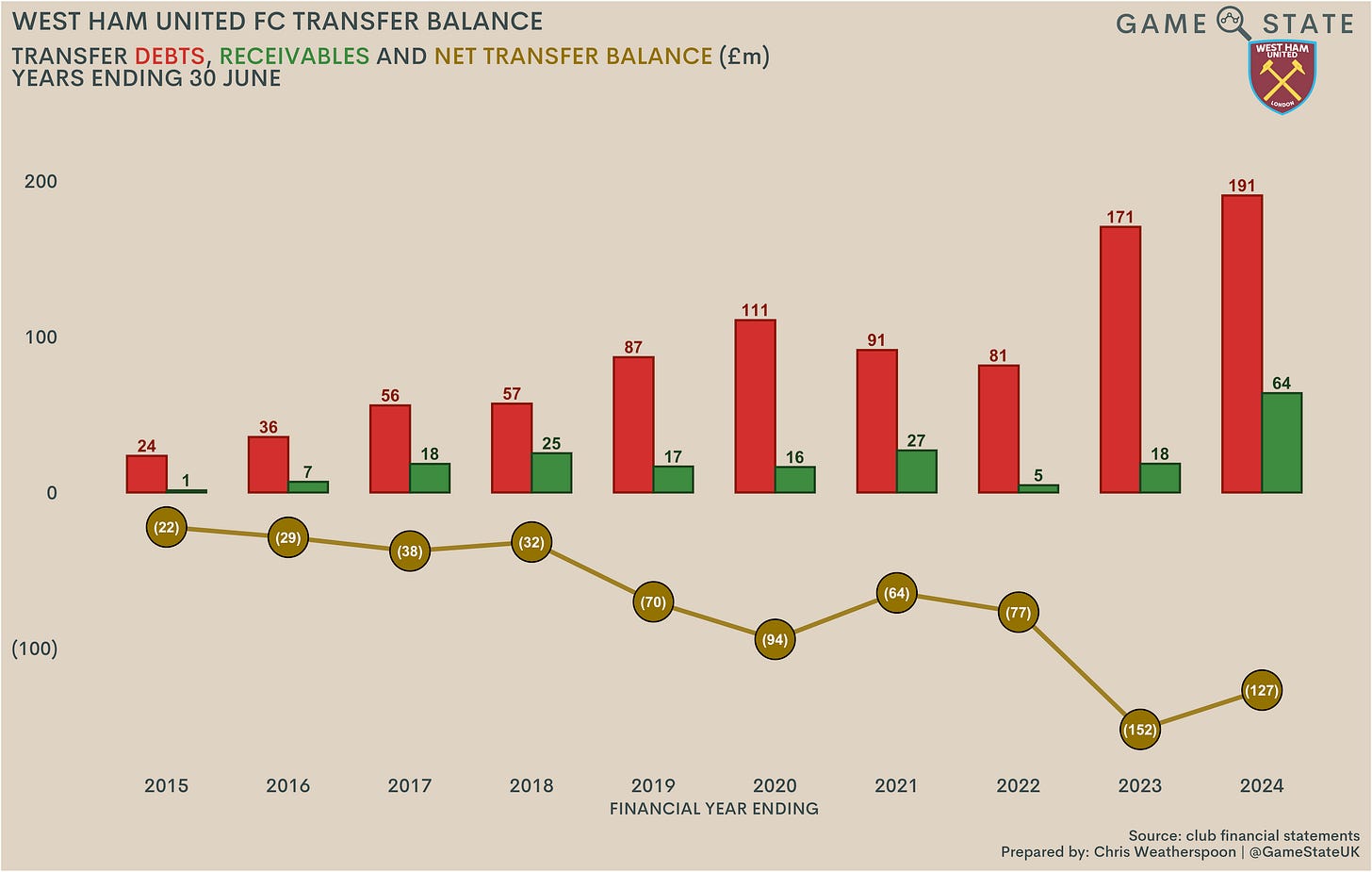

Curiously, despite the bumper sale of Rice, West Ham’s net transfer balance (amounts owed to clubs less amounts due from clubs) only improved by £25 million in 2024, sitting in a net payable position of £127 million at the end of May 2024.

That’s explained by a strategy the club has employed around that Rice fee (and possibly some others too) to accelerate receipts of the cash owed. As many clubs pay in instalments, clubs often ‘factor’ their transfer receivables, whereby a third party will pay them the money owed now in exchange for a haircut (effectively, an interest charge). That third party then takes the transfer fee back as repayment once the club receives it.

West Ham haven’t quite factored recent receivables in the way many other clubs do - no loan balance now sits on the club’s books - instead signing away their right to the fee owed to them for Rice and/or others. As a result, the club's transfer receivable balance drops, as they’ve signed away the amounts owed to them in future in exchange for smaller amount of cash today.

To this end, in 2023/24, the club received £28.2 million from Barclays in respect of £30 million due to them in transfer fees, the £1.8 million difference being Barclays payment for providing accelerated funds (this cost sits within the club’s interest paid figure). In 2024/25, The Hammers repeated the strategy, this time opting to receive £64.0 million from Barclays now, in exchange for £69.2 million in transfer fees due.

Not all EPL clubs disclose their transfer balances, but West Ham’s £127 million owing was one of the poorer figures at last check. Eight clubs owe others more than £100 million in outstanding transfer fees, with only Brighton bucking the negative trend with their £87 million net transfer fees receivable.

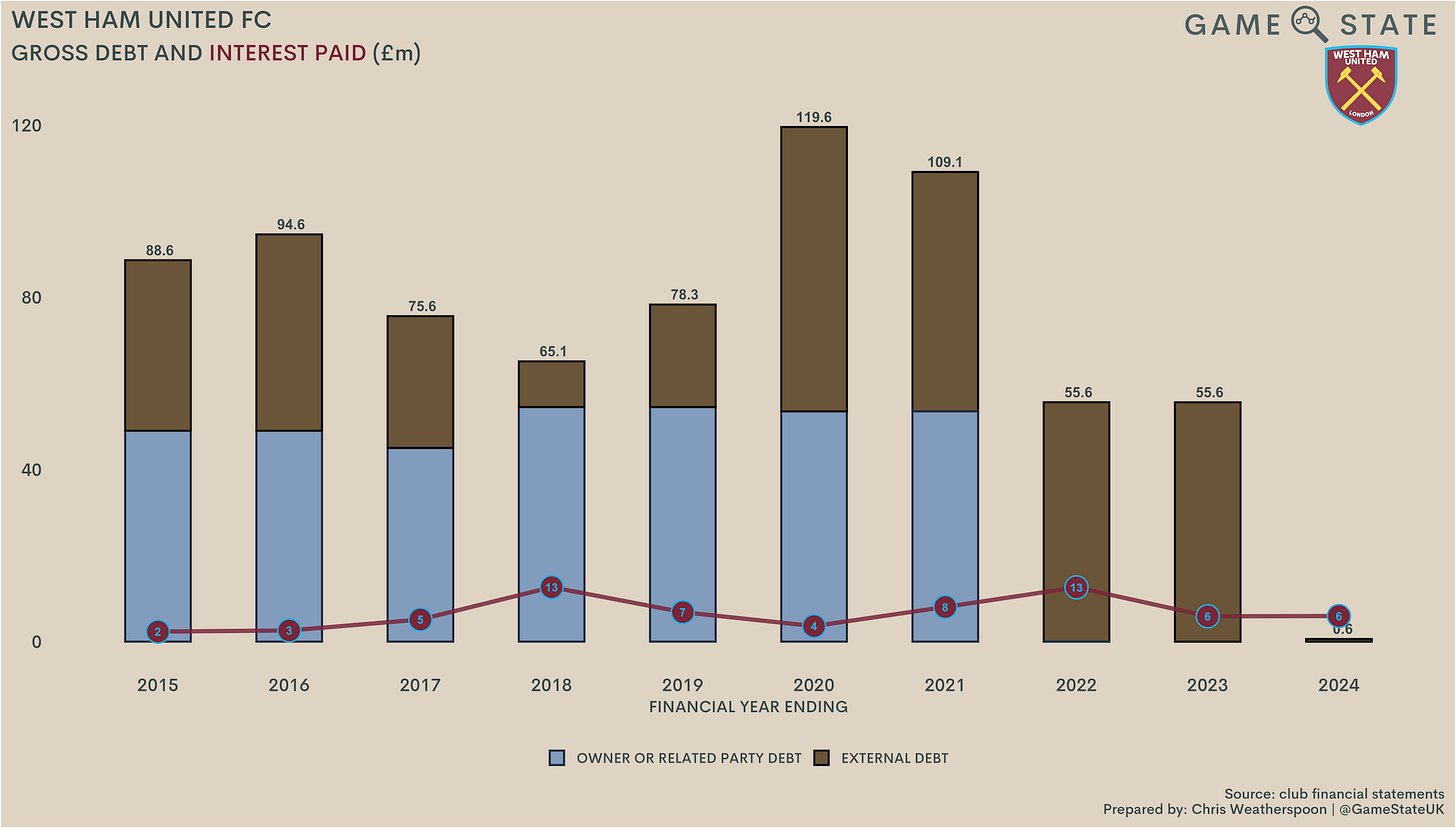

Financial debt

West Hams gross debt hit £120 million during the pandemic, as existing owner loans were topped up by a £55 million loan from lender MSD Holdings, drawn down in March 2021 and used to pay off existing external loans that were close to maturity. That MSD facility totalled £120 million, though the club never drew down beyond that initial £55 million.

Since then, the club has reduced its debt dramatically. In 2021/22, utilising funding generated following Daniel Křetínský’s purchase of a 27 per cent stake in November 2021, The Hammers paid off £54 million due to existing owners David Gold and David Sullivan. That left only the MSD debt on the books, which remained unchanged until August 2023 when, following the sale of Rice, the club opted to pay it off in full, a strategy the directors stated was in line with the desire to ‘optimise [club] funding’.

West Ham still held a short-term, £40 million overdraft facility with Barclays (renewed for another year in June 2024) to call on as required but, to all intents and purposes, the club was debt-free at the end of May. Subsequent to the year end, they took out a small £5 million term loan with Barclays to support the redevelopment of the club’s training ground.

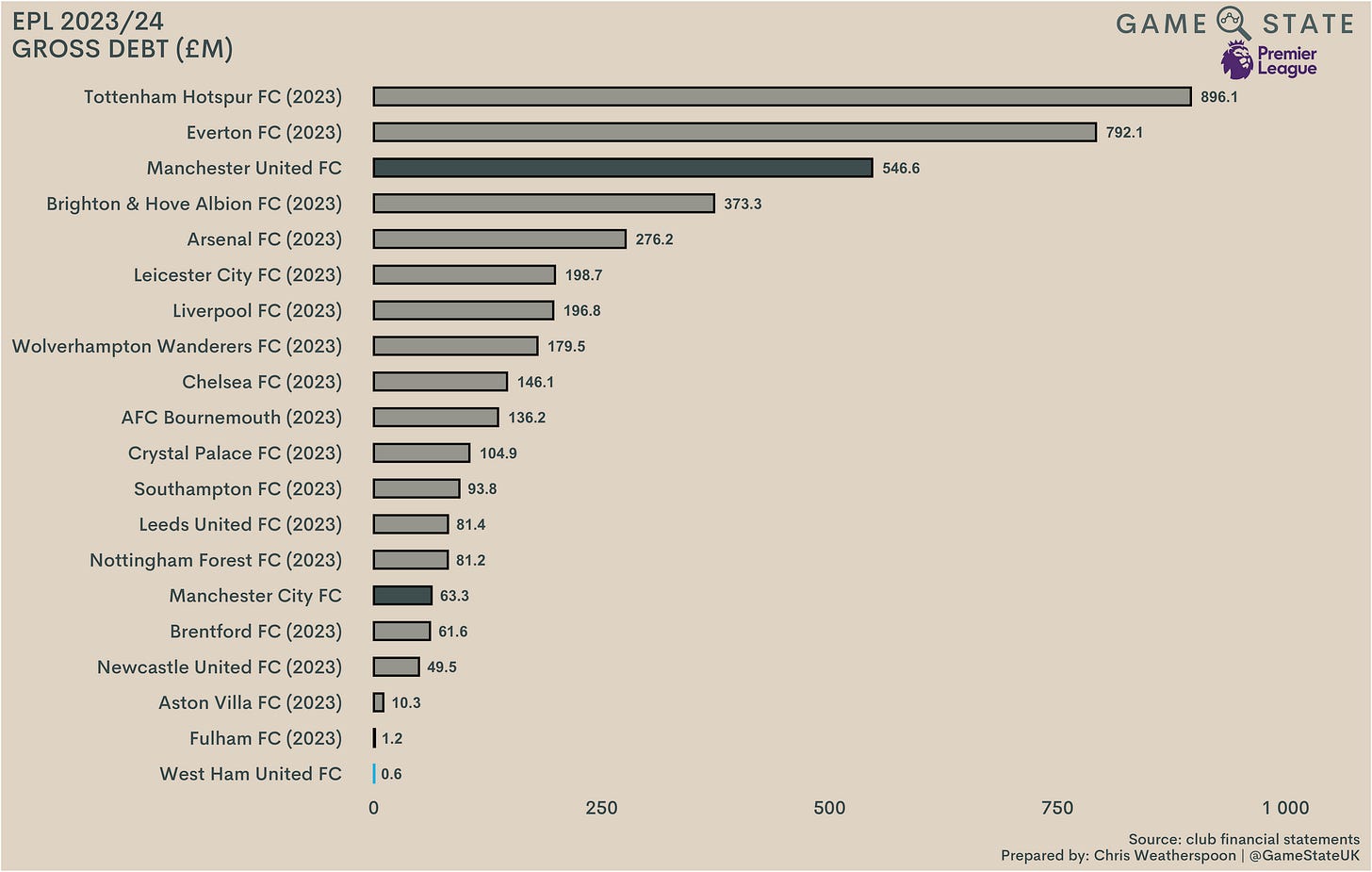

As a result, using most recently published financials, West Ham are the least indebted club in the top tier, which sounds particularly impressive that the division’s combined gross debt figure sits at £4.3 billion. That said, the spread of debt across the EPL is far from equal; just four clubs account for 61 per cent of the total figure.

Large debt isn’t necessarily a bad thing, provided businesses can service what they owe. That’s true in football too, and though West Ham’s debt never incurred especially large interest costs, the removal of that debt isn’t without impact on the day-to-day. The exact rate on the MSD loan was never disclosed, but the lender’s 2021 financial statements confirmed its existing loans to clubs incurred interest of between 8.91 and 13.01 per cent. The consensus, backed up by the club’s accounts, is that The Hammers paid between nine and 10 per cent each year, so removal of that will free up in the region of £5 million per year going forward.

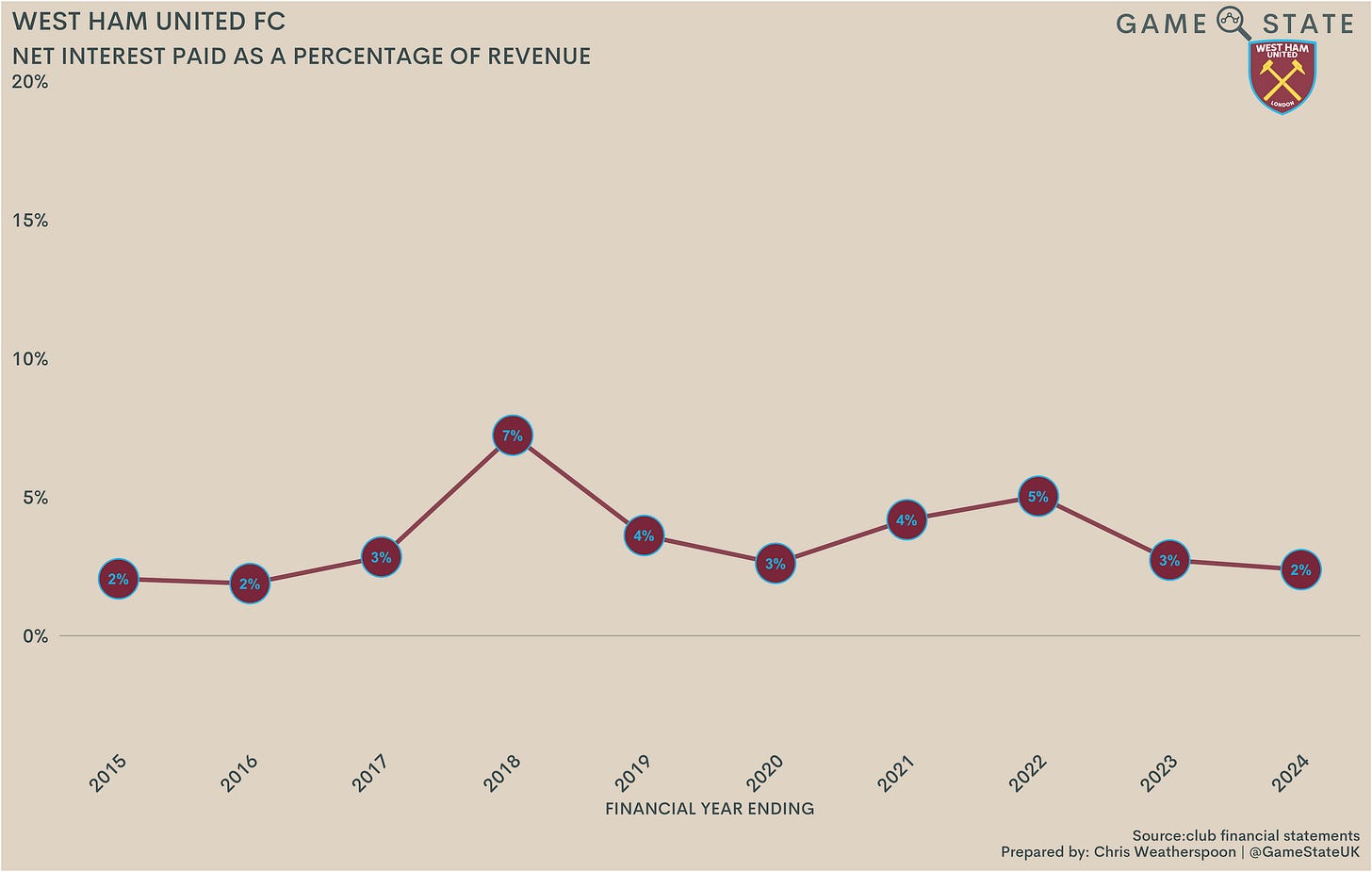

Comparative to revenue, the amounts West Ham have paid out in (net) interest costs have been low and getting lower, a trend which will continue in relation to financing of loans. Having said that, that £5.1 million incurred on accelerating future transfer fees will mean the overall interest paid in 2025 won’t differ materially from 2024.

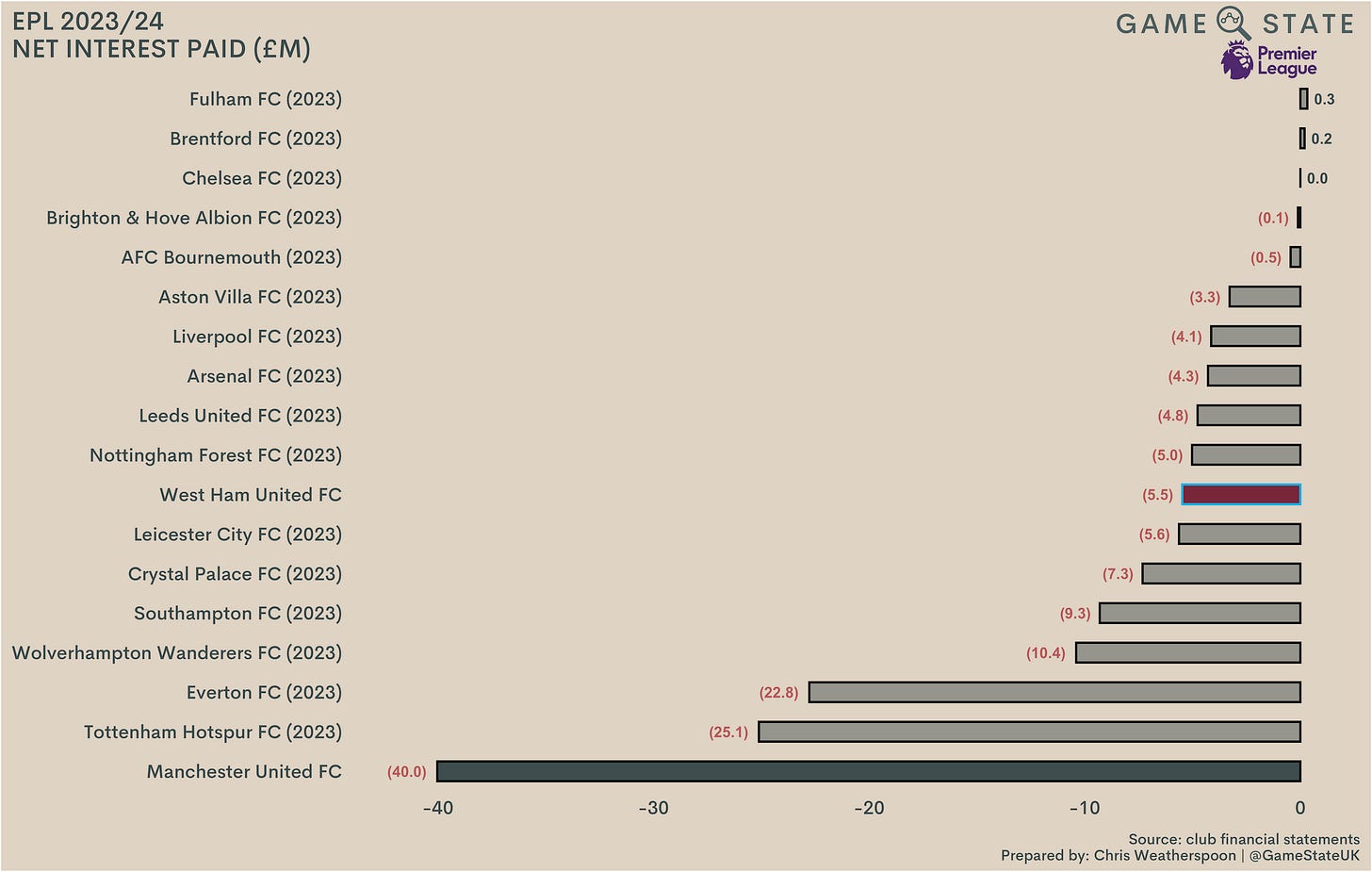

On a net basis, West Ham’s £6 million interest paid last season was fairly middling for the EPL, and should remain so this year (i.e. taking into account the cost of those accelerated transfer fees receivable). The Hammers’ finance costs are a long way shy of the amounts recently forked out at Manchester United, Tottenham Hotspur and Everton.

Cash flow

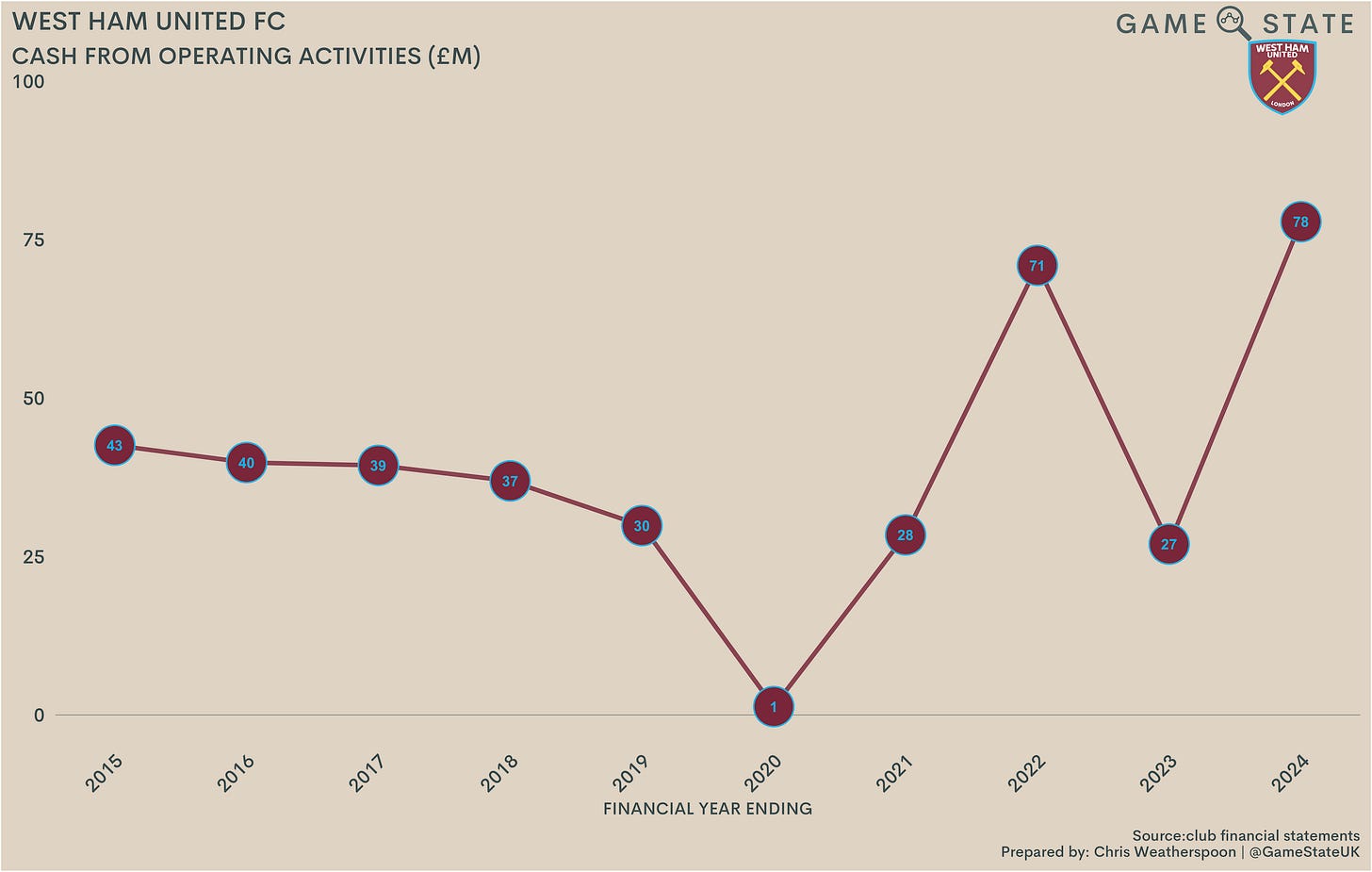

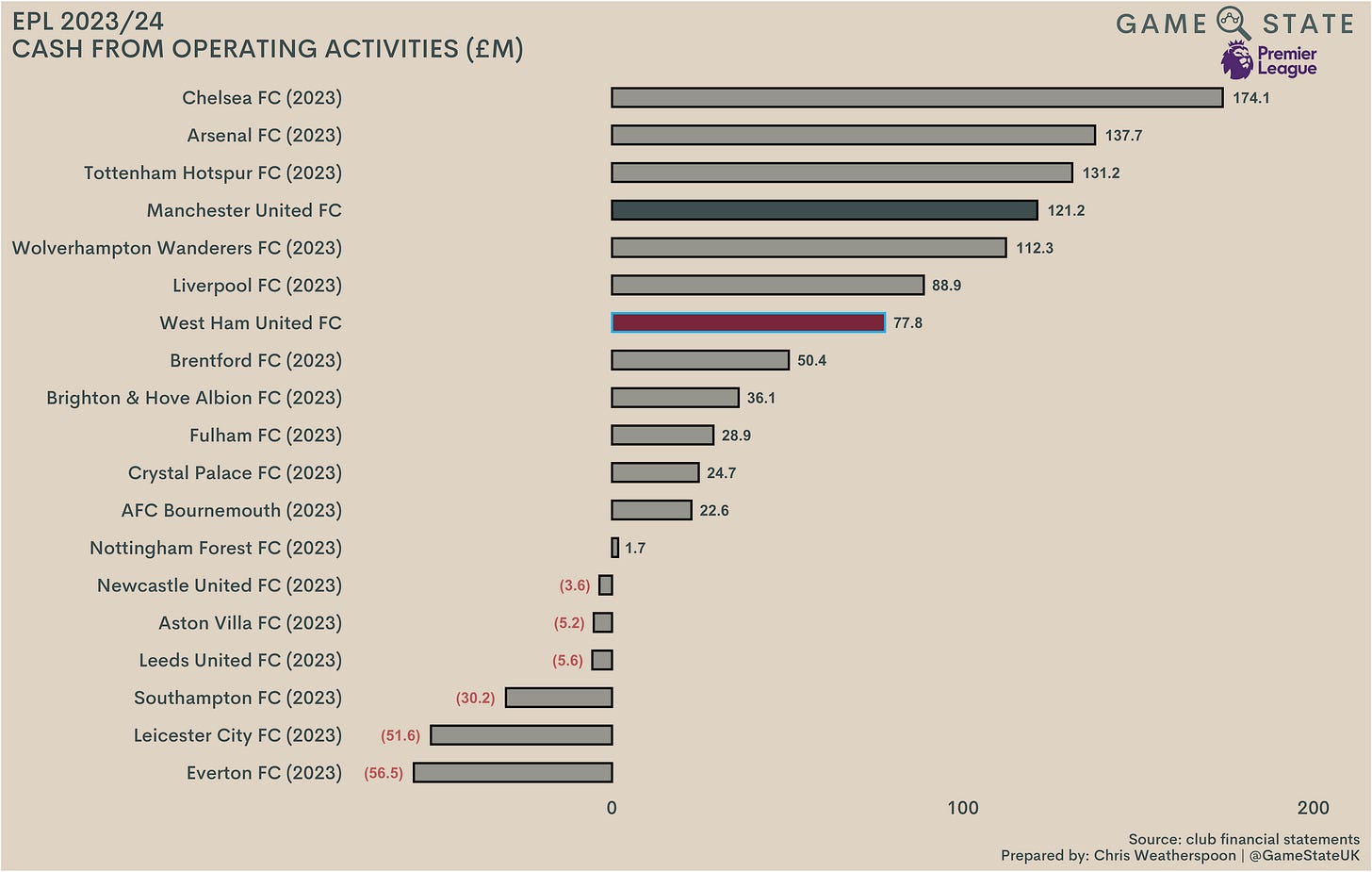

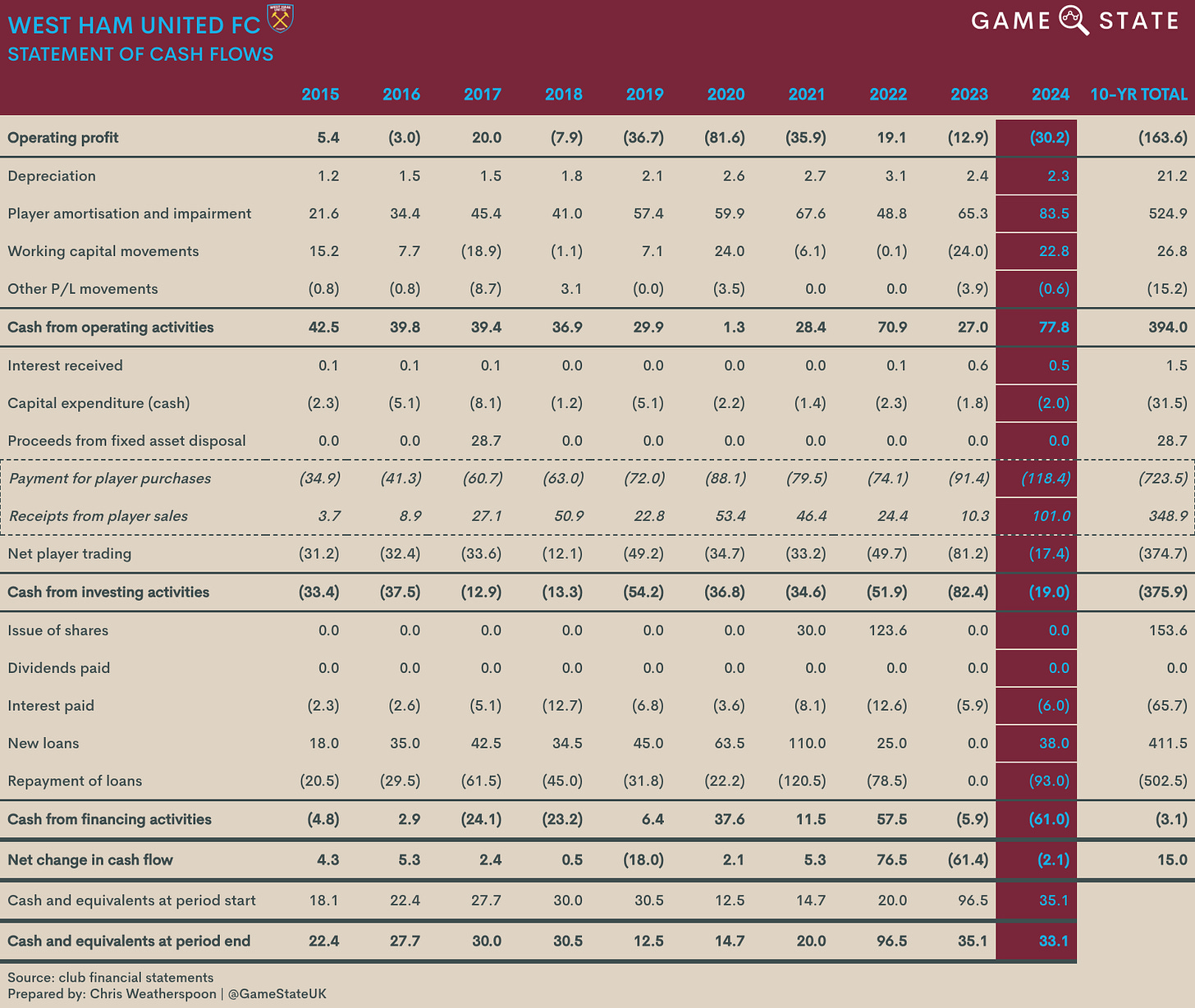

West Ham have been consistently cash-positive at the operating level in the last 10 years, even generating (small) positive cash flow in Covid-hit 2020. In all, The Hammers have generated £394 million cash from operations since 2015. Before transfer dealings, West Ham make cash at the operating level, topping £70 million in two of the last three years. From a profit and loss perspective, the costs of amortising transfer fees push

Because transfers now account for so much of club spending in the EPL, top tier sides have generally been cash-positive in the operating sense. 14 clubs had positive operating cash flow, and five of those made over £100 million cash from the day-to-day. West Ham’s result was the seventh-best here, or possibly eighth (Manchester City don’t publish a cash flow statement), in a division where clubs collectively made £855 million in operating cash at last check.

Over the last decade, West Ham have received cash inflows of £576 million, split £394 million cash from operations, £154 million from share issues and £29 million in proceeds from the sale of Upton Park in 2017. In turn, that £576 million has been spent on:

£375 million net player trading;

£91 million net loan repayments;

£64 million interest payments;

£31 million capital expenditure on infrastructure; and

£15 million increase in cash balance.

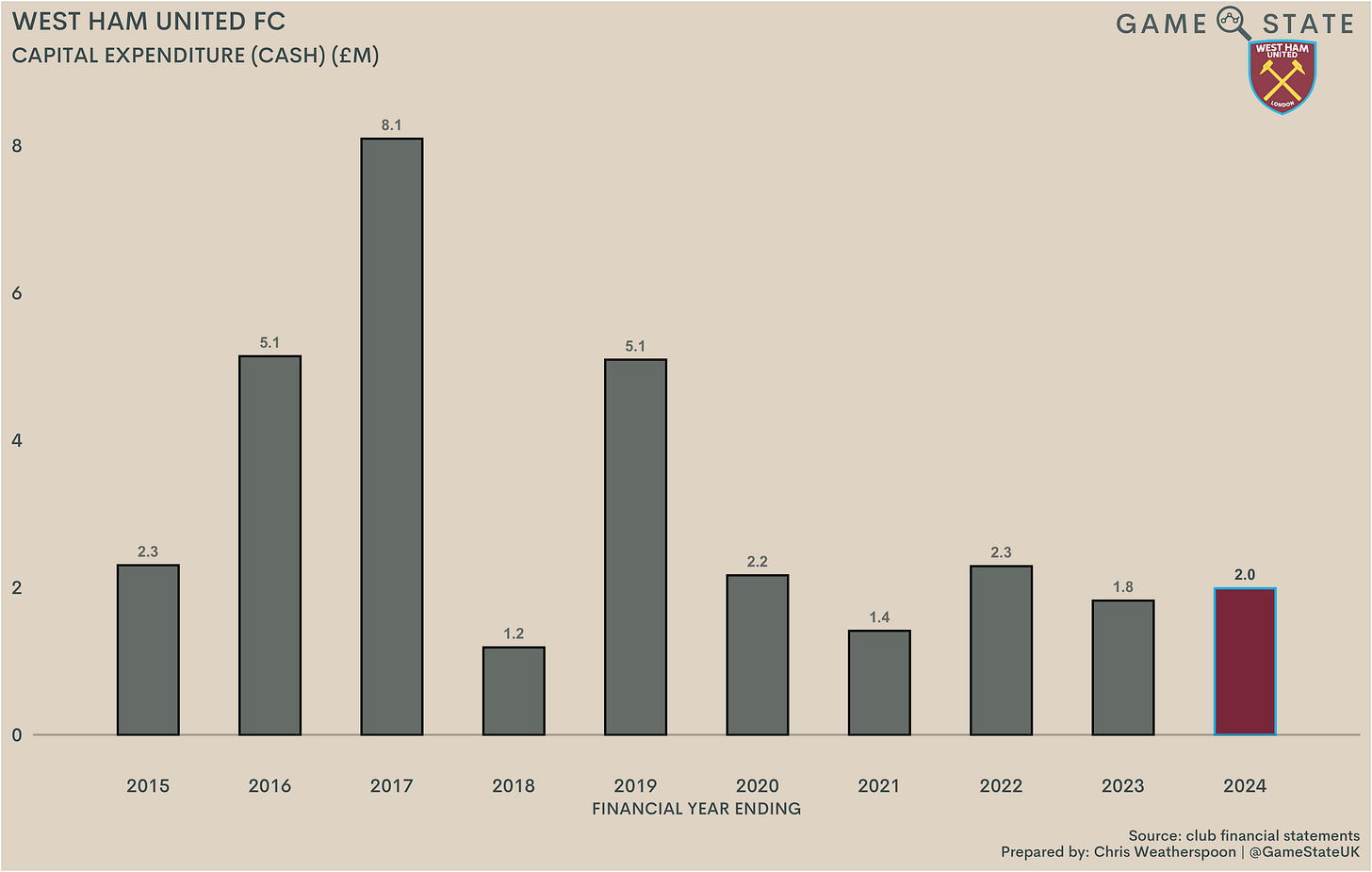

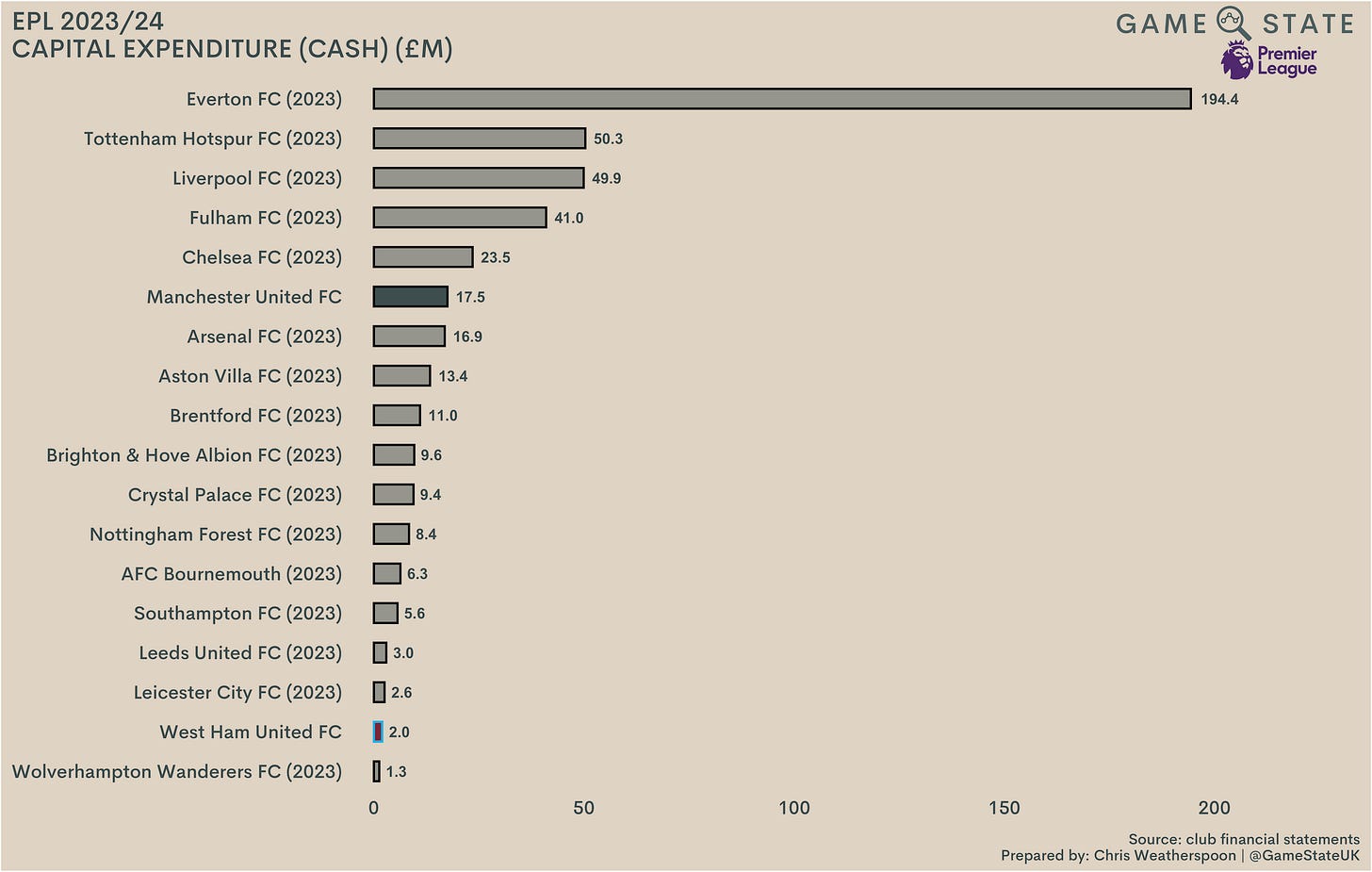

In a decade where the club moved into a 60,000-plus-seater stadium, it seems odd to see West Ham only spent £31 million on capital expenditure in that period. Of course, that’s because they lease the London Stadium and, what’s more, aren’t on the hook for improvements to the ground.

The Hammers’ annual capital spend has therefore been consistently low, levelling out at around £2 million in recent years, though that will increase in 2025 with the (at least) £5 million invested in improvements to the Rush Green training facility.

Unsurprisingly, £2 million was one of the lowest capital spends in the EPL last season, though it’s also true that clubs generally don’t commit tens of millions here unless investing in larger-scale infrastructure projects.

Owner funding

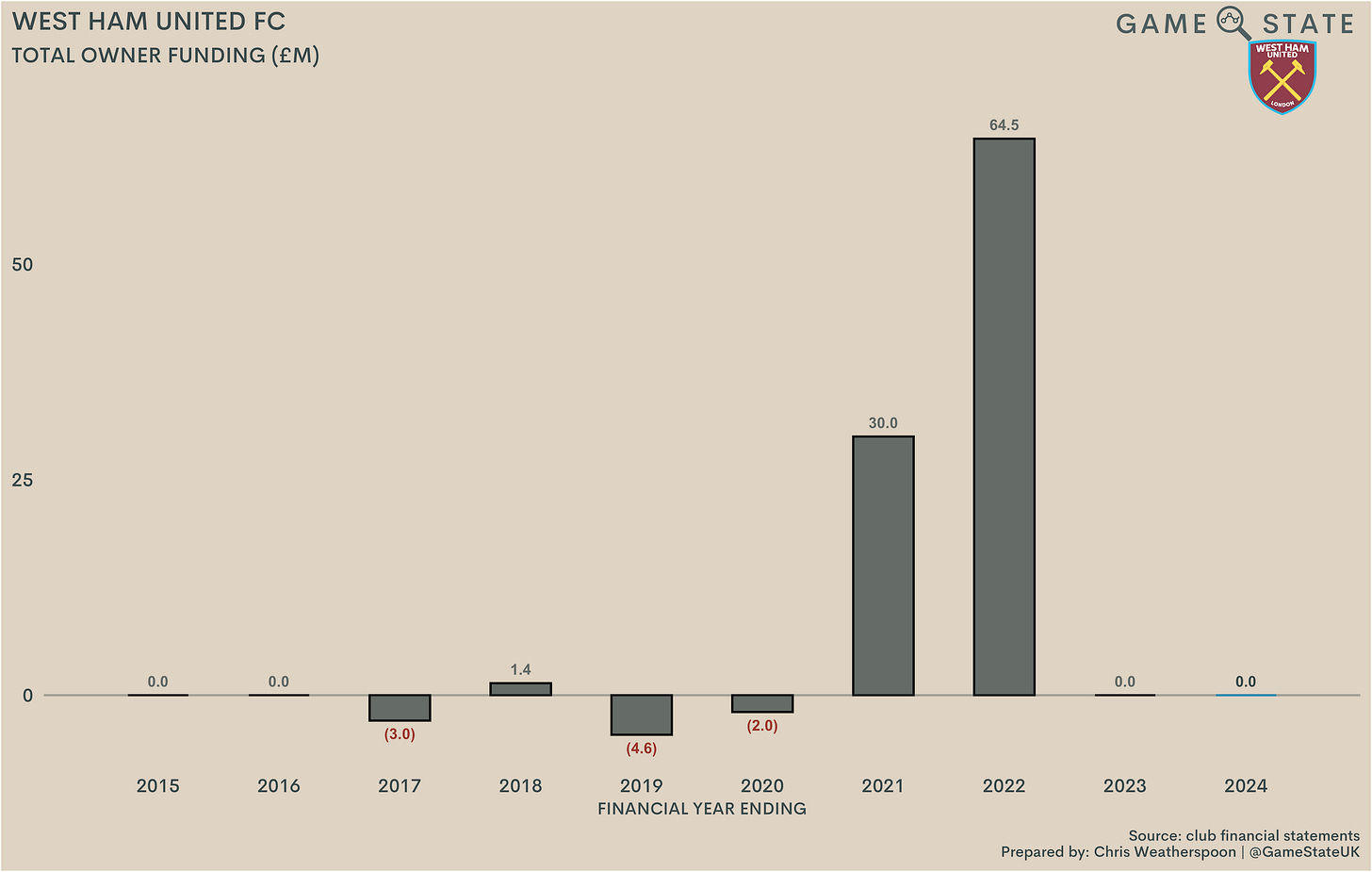

For the second year running, West Ham received no new cash from their owners, though this is more in keeping with the years before Křetínský’s 2021 arrival. In fact, The Hammers owner funding was negative for several years in the first half of the last decade, as David Sullivan and David Gold started receiving annual interest payments on their loans to the club.

Křetínský’s buying of shares changed that, as the two existing owners saw their loans fully repaid. West Ham received a £124 million share injection when Křetínský joined, but around £59 million of that went on repaying existing owner loans and interest that had accrued on them. In all, The Hammers have received £86 million in owner funding over the last decade.

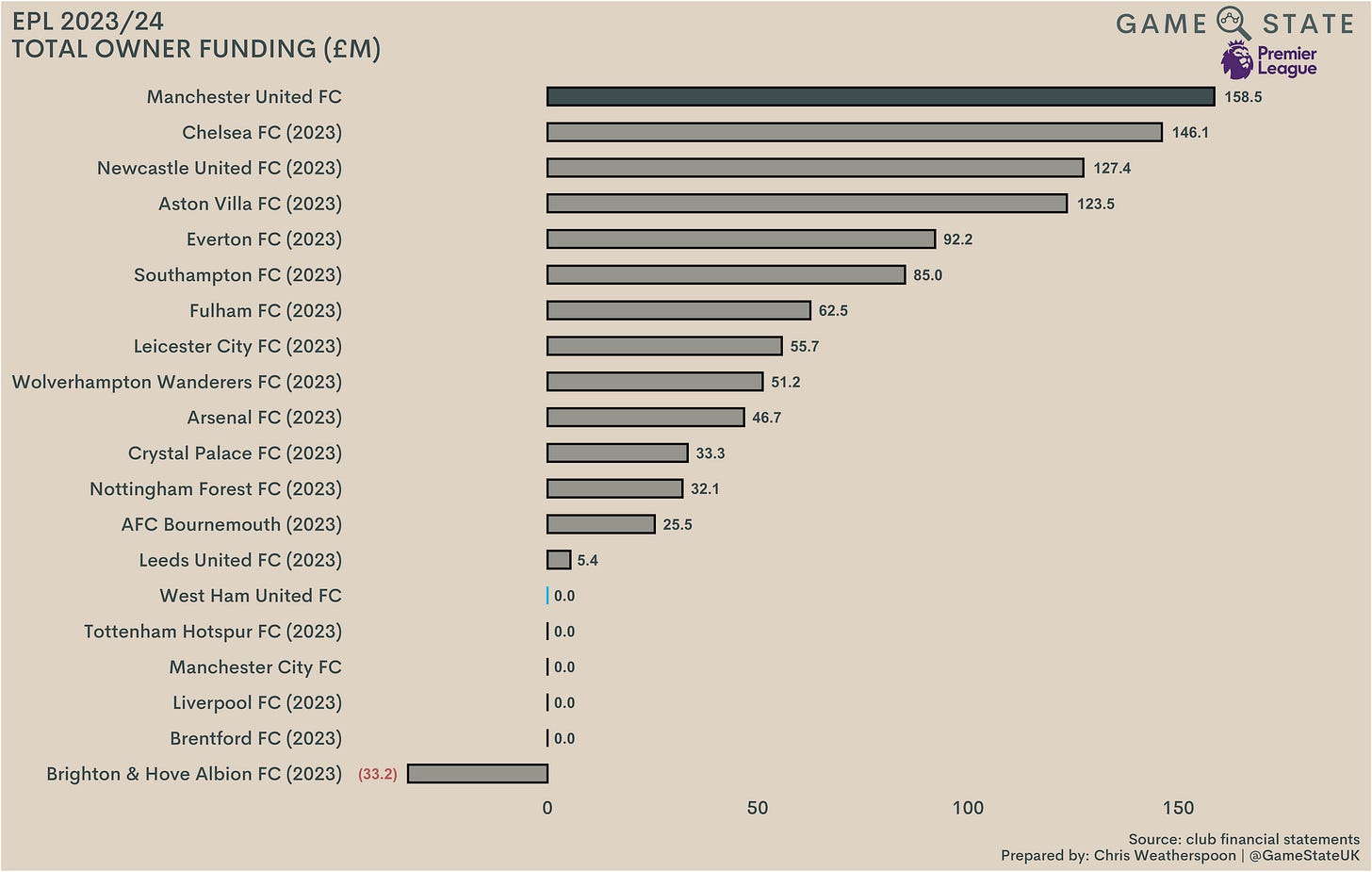

The Hammers were one of six clubs to receive no or negative owner funding in their most recently published financials. Even so, EPL clubs still received £1.012 billion from their owners in a single year, and it’s of note that three of the top five in 2022/23 were Newcastle United, Aston Villa and Everton, all clubs that West Ham have feasibly been looking to beat in the race to break into England’s elite.

In a cumulative sense, West Ham’s £86 million in owner funding in the last 10 years is very much at the low end of the EPL, a long way behind the likes of Everton (£771 million to end of 2022/23), Chelsea (£639 million), Fulham (£619 million) Aston Villa (£574 million).

Profit and Sustainability Rules (PSR)

Domestic

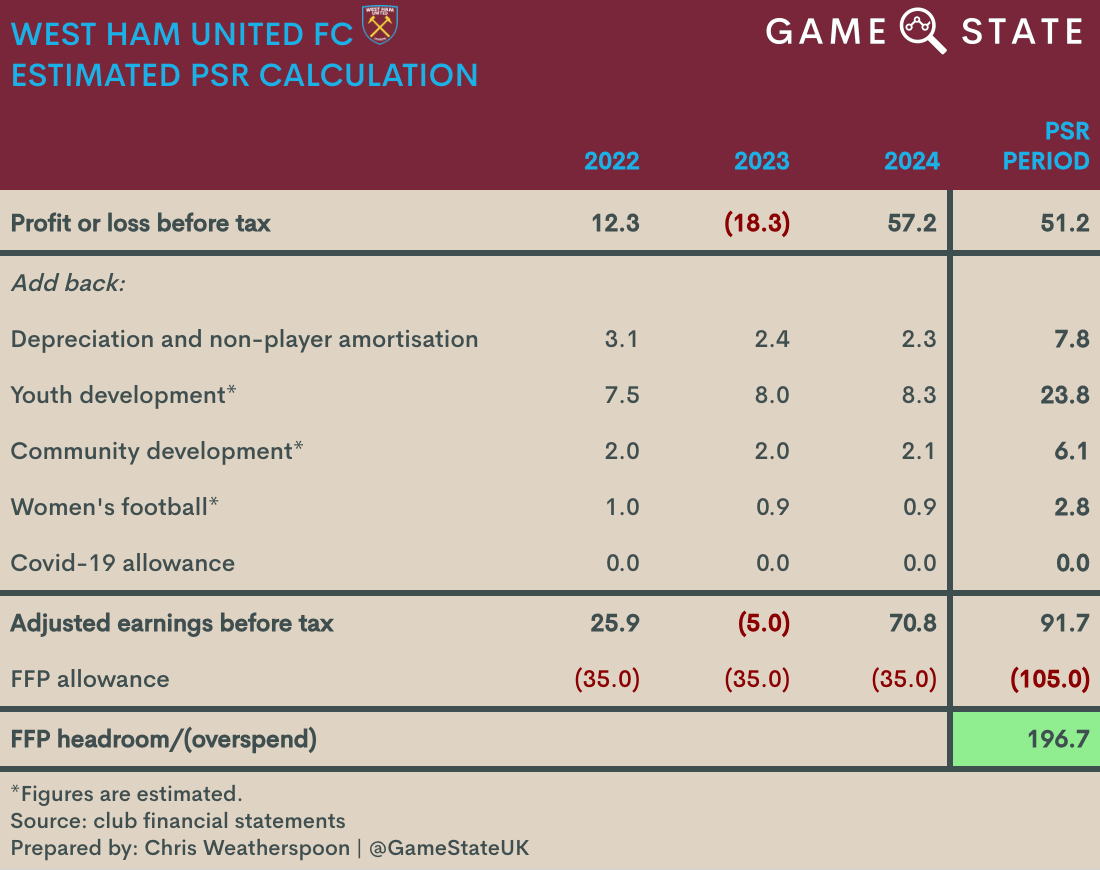

Believe it or not, after two profit-making years in the last three, West Ham had little to worry about from a domestic PSR perspective. Even before deductions, the hammers pre-tax profit over the relevant period was £92 million. After them, per our model, we estimate West Ham had £197 million of headroom when it come to compliance with EPL PSR rules.

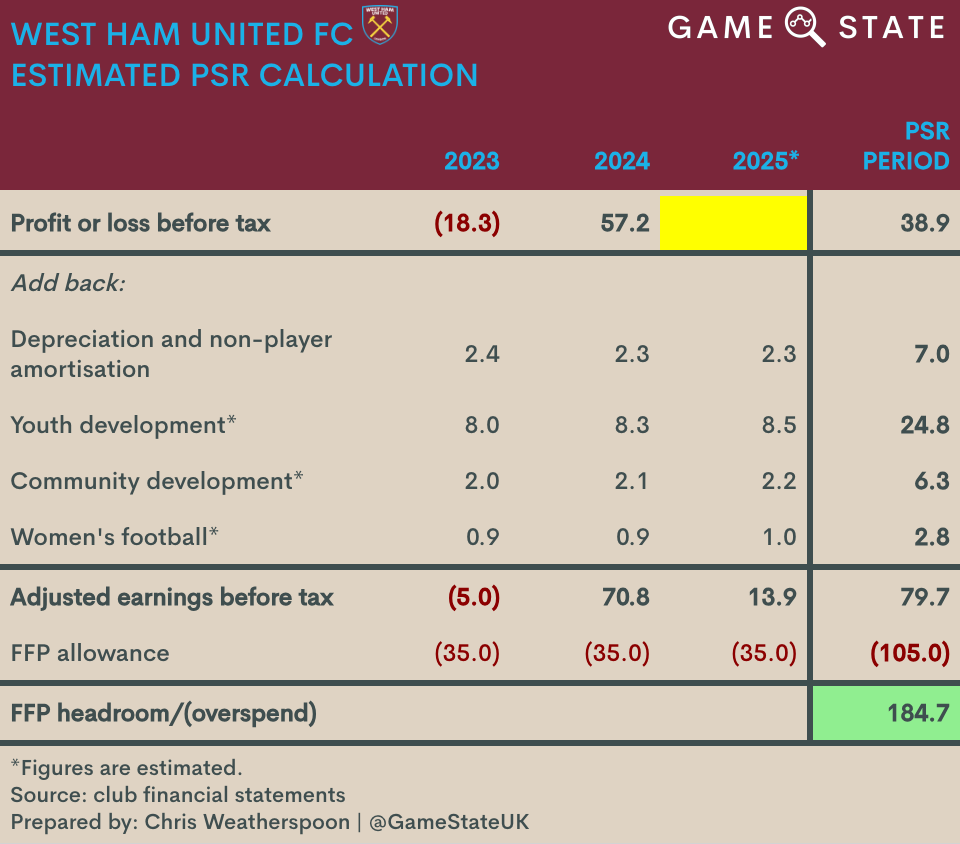

Similarly, the club will little trouble this season, even if they return to making losses. Past equity injections from the ownership ensure the club’s loss limit across the three-year period is £105 million, and flowing from that we estimated West Ham could lose £185 million this season and remain compliant with PSR. Safe to say, they won’t lose anywhere near that amount.

UEFA

While they missed out on European competition in the current season, last year’s Europa League campaign meant West Ham were also required to comply with UEFA’s separate financial rules. Those come in two broader categories (ignoring, for now, some more minor elements clubs must comply with):

Football earnings rule, which looks to limit club losses, much like the EPL’s PSR rules; and

Squad Cost Ratio (SCR), which looks to limit how much clubs can spend directly on its football staff.

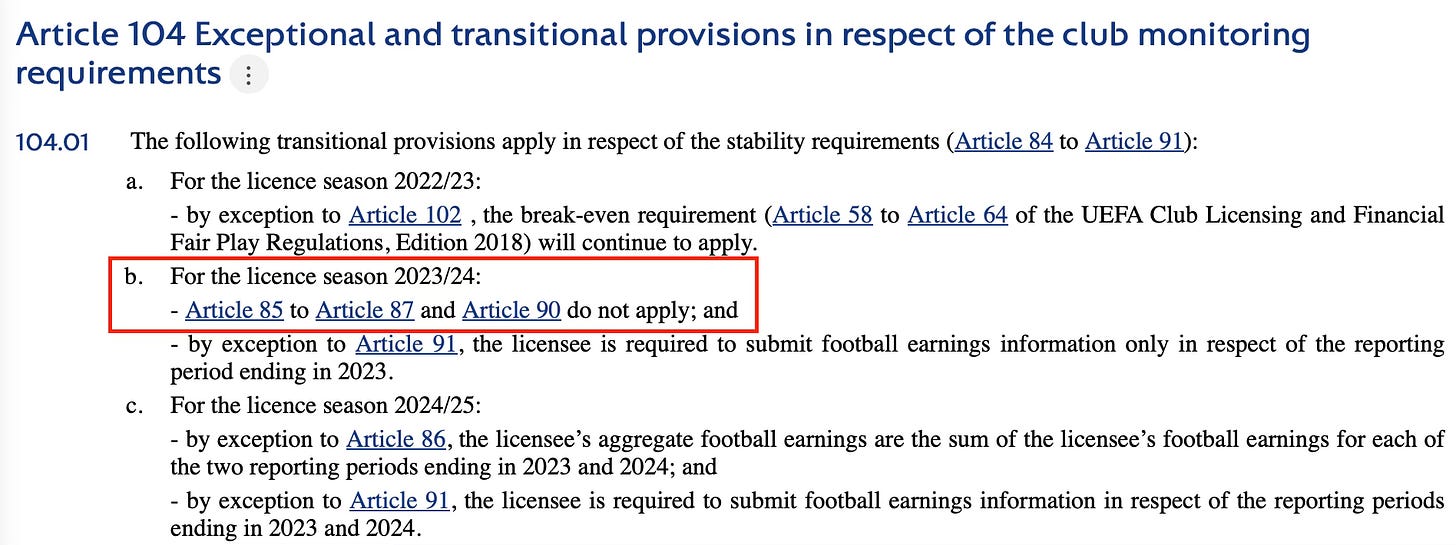

In 2023/24, the football earnings rule wasn’t a consideration for West Ham - or anyone else. Per UEFA’s transitional provisions, while clubs were required to submit a year’s worth of football earnings information for monitoring purposes, Article 90 didn’t apply:

That’s not the case in 2024/25, but with West Ham absent from Europe this year, it isn’t something they need to worry about. In any case, this element of UEFA’s rule is similar to the EPL’s financial restrictions, so The Hammers would have had no trouble in complying anyway.

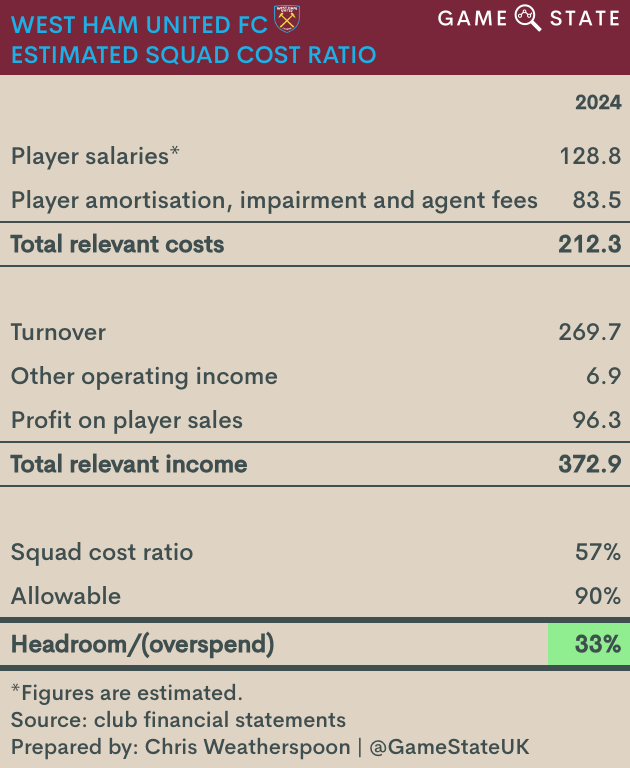

UEFA’s SCR limits obviously don’t apply to West Ham this year either, but they did last season. In 2023/24 clubs were limited to spending 90 per cent of their relevant income (not the same as a club’s turnover figure) on relevant, squad-related costs.

Player salaries aren’t disclosed by West Ham (nor are they by many English clubs), but based on information from a UEFA report we know that the club’s player wages made up roughly 80 per cent of their total wage bill in 2020. Applying that figure to 2024 staff costs provides an estimated figure of £129 million, which when added to last season’s amortisation charge gives us a total cost base for SCR purposes of £212 million.

In turn, West Ham’s relevant turnover was £373 million. That produces an SCR of 57 per cent for 2023/24, 33 per cent below the applicable limit last season.

That acceptable limit is tapering down. This season, participating clubs are limited to spending 80 per cent of relevant income on squad costs; in 2025/26 that figure drops to 70 per cent, where it will stay. Based on most recent figures, West Ham will be fine if they do make a (currently unlikely) return to UEFA competition next season, though continued investment in the playing squad means they are probably closer to the 70 per cent limit now than previously.

The future

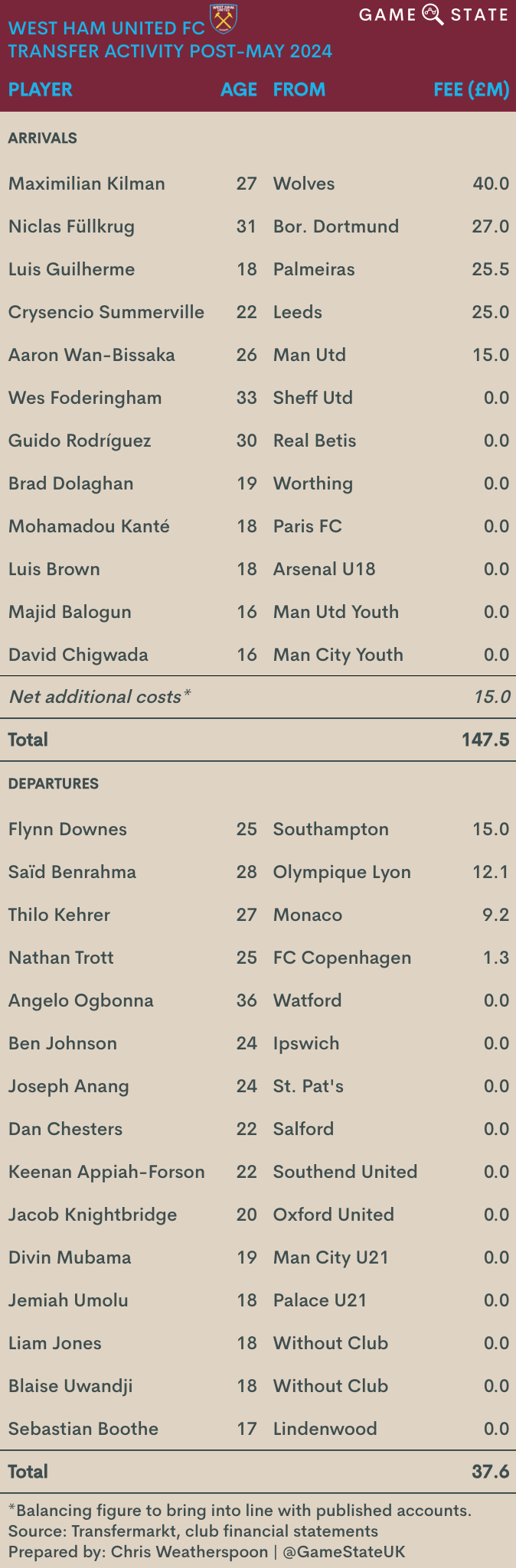

As highlighted earlier, West Ham didn’t exactly skimp in the summer 2024 transfer market, racking up a net spend of £110 million. The club didn’t disclose the split of purchases and sales for that window, but when trying to align with publicly reported fees it becomes apparent The Hammers spent more on incoming transfers than media reports already suggested, possibly because of agent fees. Our rough estimate is that West Ham spent £148 million on new signings last summer, with £38 million in return for players sold.

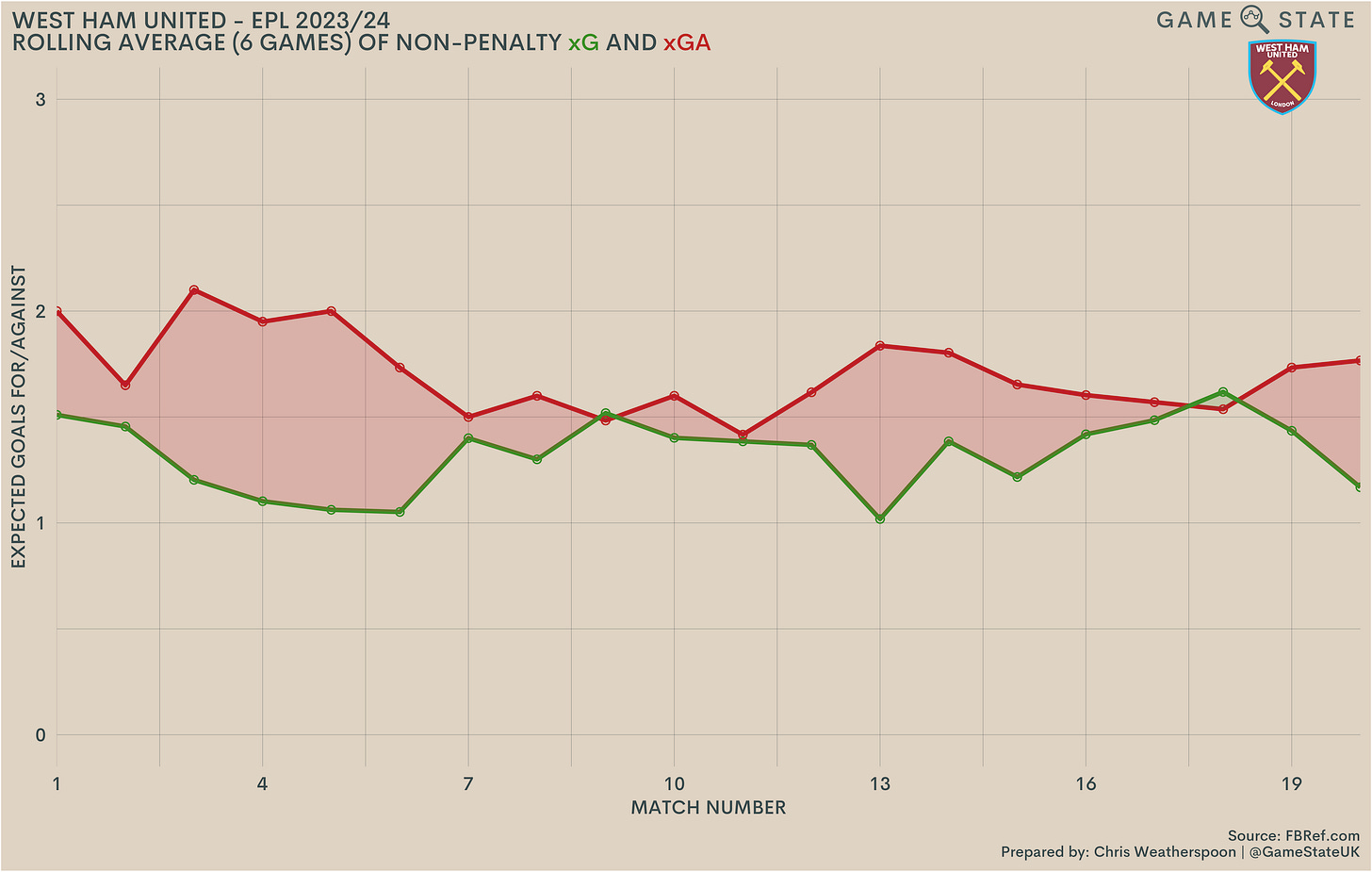

West Ham’s 2024/25 season so far has been fairly grim, at least by the club’s recent standards. That transfer activity, combined with replacing David Moyes with Julen Lopetegui in the dugout, had Hammers fans optimistic the club could push on once more. To say Lopetegui’s reign was a disappointment would be an understatement; he was sacked on 8 January, replaced by former Brighton and Chelsea boss Graham Potter a day later.

Whether Potter can inspire an improvement remains to be seen but, other than a four-game unbeaten run in December, Lopetegui’s time in charge brought little joy. That run was followed by successive spankings against Liverpool and Manchester City, leading the club’s board to cut loose a manager they’d been rumoured to have lost faith in well before the axe eventually fell.

At the time of writing, West Ham sit 14th in the league having lost nine of their first 20 games. They sit closer to the relegation zone than a European berth, despite another summer of £100 million-plus investment in the playing squad. Potter, who has signed a two-and-a-half year contract, will be expected to return The Hammers to competing with those clubs just outside England’s elite.

West Ham’s finances are pretty strong, and they’re one of the few English clubs in recent years who’ve managed to turn profits with any regularity. The club displays consistently strong wage control, has shown impressive matchday and commercial income growth and, yes, benefits from a hugely generous stadium lease. They are also in the midst of trying to claw back a £4 million payment made to landlords LLDC, which would further sweeten that deal if successful.

All that being said, there is cause for wariness in East London. A first season in four without European football will impact revenues, and after another sizeable summer transfer spend it’s unlikely the club’s wage bill has dropped. Expect their wages to revenue metric to go up this season.

Likewise the club will be hoping Potter can turn around domestic fortunes fast, for reasons both sporting and financial. Every dropped position in the EPL now equates to around a £3 million annual reduction in merit payment; The Hammers’ current position of 14th would therefore translate to a further £15 million income drop on 2024, to go with that lost European income.

While the arrival of Křetínský in late 2021 has inspired an increase in owner funding, The Hammers remain a club that generally runs itself out of its own resources. That’s commendable, and while the directors admit in the latest accounts further funding - either from themselves or third parties - will be needed in the next 12 months (primarily to fund the recent transfer fee commitments), that will likely pale in comparison to the clubs West Ham are directly competing with.

Křetínský arrived at West Ham just a month after Newcastle United were taken over by the Public Investment Fund of Saudi Arabia. Between then and the end of 2024, Newcastle’s cash owner funding sits at £335 million. At Aston Villa, the figure injected into the club’s holding company in the same period is £352 million. Both are an order of magnitude larger than West Ham’s £96 million from November 2021 to the end of May 2024.

West Ham have done well to compete as they have in the last decade, and 13 straight seasons in the top tier represents genuine stability for the club. European success is hardly to be sniffed at either. But, without a strategic shift from the club’s owners, The Hammers will need to get back on track soon - or risk seeing rivals with greater financial backing pull off into the distance.