Club financial analysis: Preston North End FC 2023/24

Game State's analysis of Preston North End FC's 2023/24 financial results.

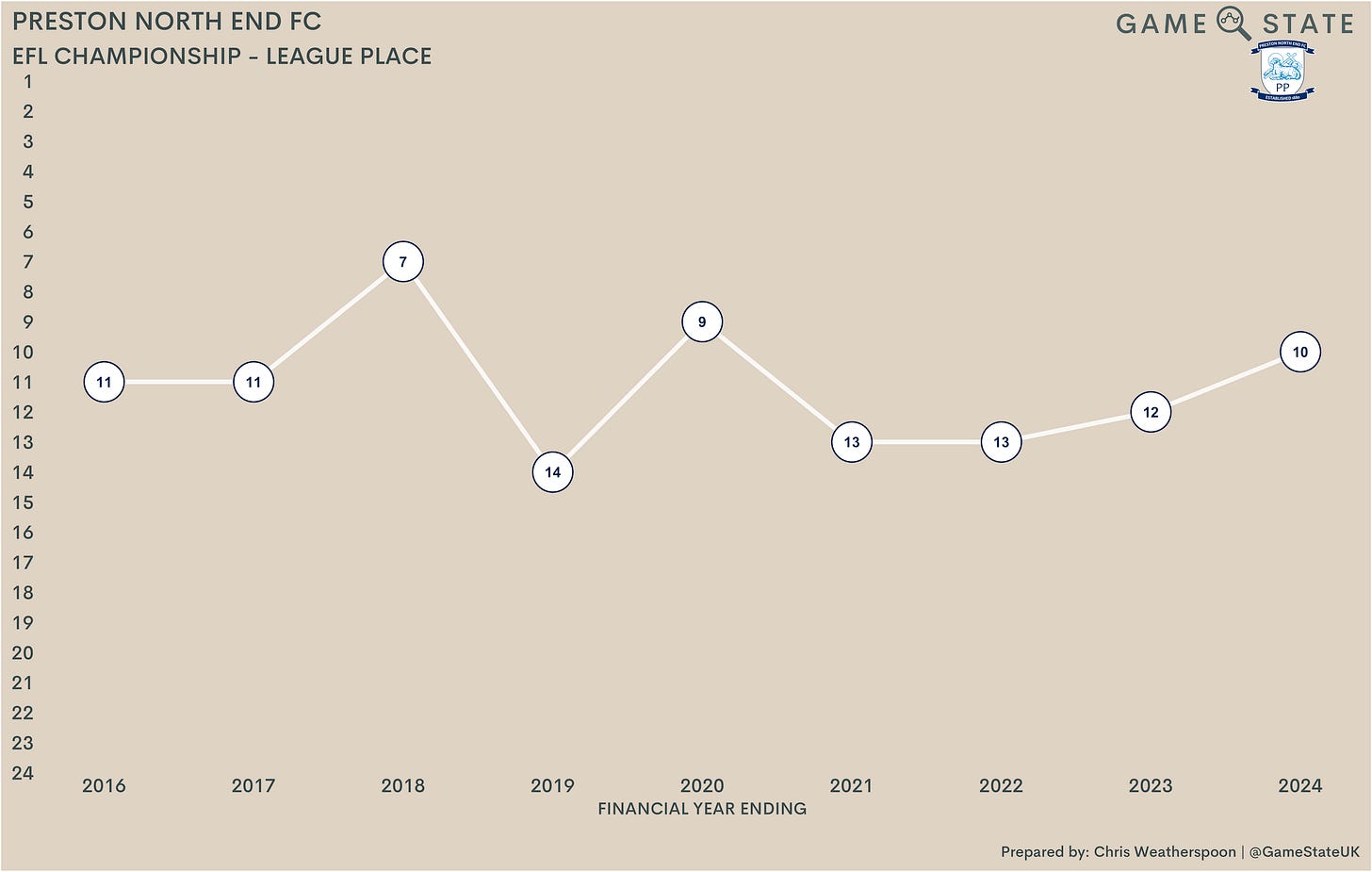

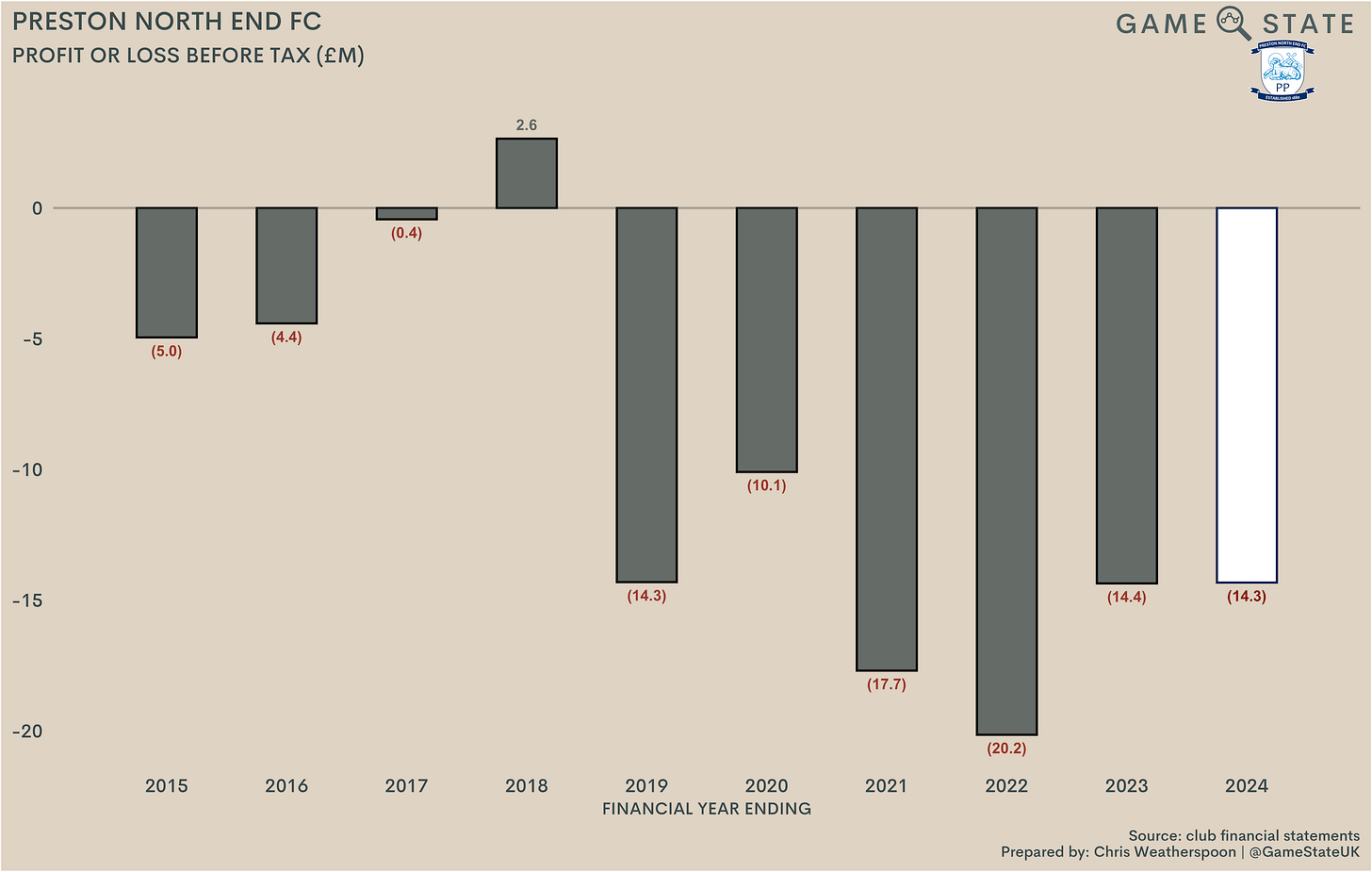

Preston North End’s unbroken tenure in the EFL Championship is into its 10th year, at a time where the club has increasingly become a byword for consistency. In each of the last nine seasons, Preston have finished in the mid- to upper mid-table spots, never dropping below 14th nor surpassing seventh. Off the pitch, the price of those mid-table showings has been remarkably consistent too. In each of the last six seasons, Preston have posted an eight-figure pre-tax loss.

The club’s bottom line hasn’t been quite so bad, as the size of their historic losses has entitled them to some chunky tax credits; Preston’s losses have been reduced in that way by £15 million across the last five years. Even so, that still amounts to a combined post-tax loss of £62 million since 2020.

2024’s loss was almost identical to that of 2023, though there were some small fluctuations in income and expenditure. A £1 million increase in broadcast, mostly brought about by increased solidarity payments from the Premier League, drove turnover to a record high £17 million, while a small increase in match day income offset rising wage costs and reduced player sales.

Current affairs

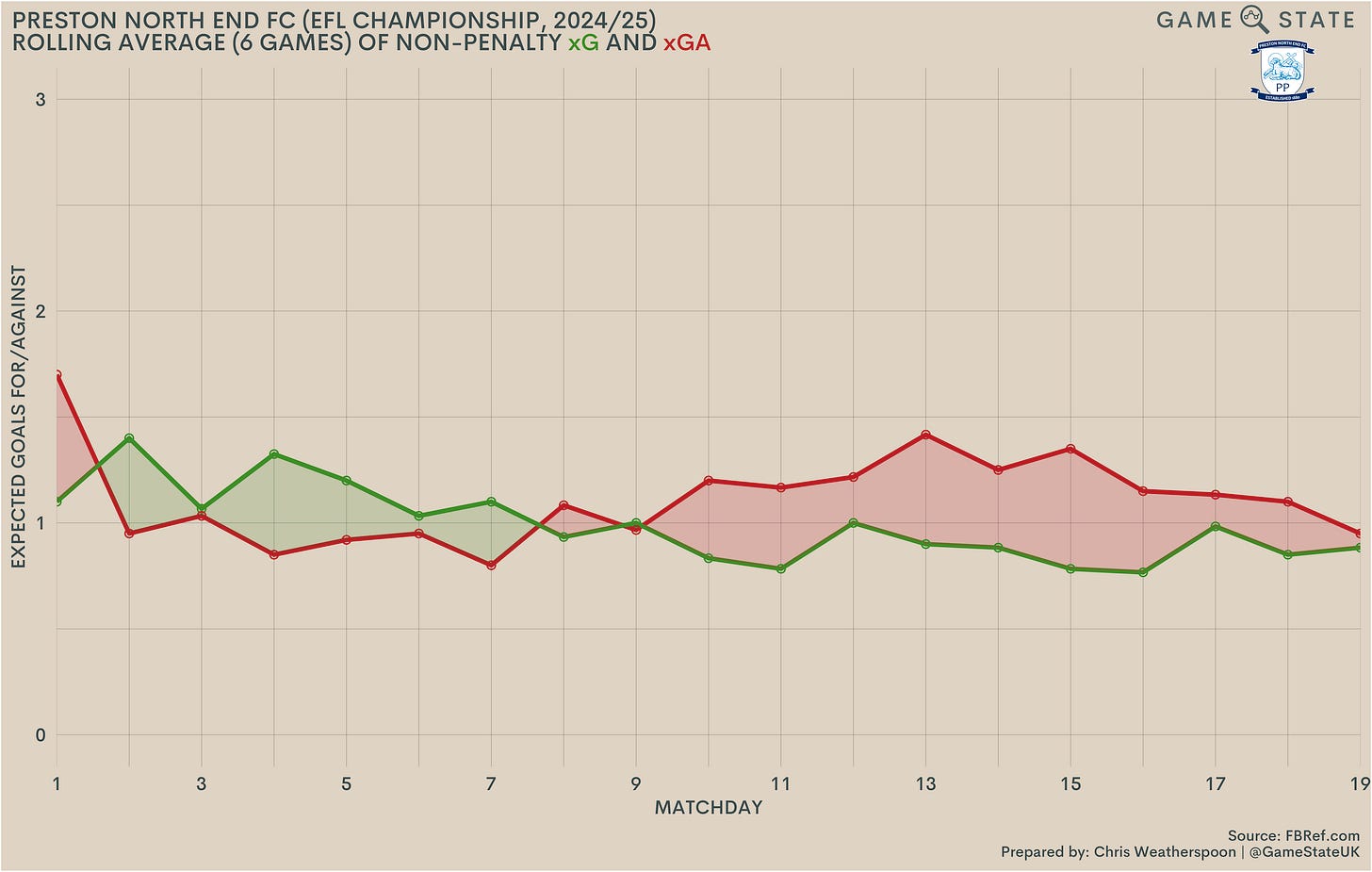

Before delving deeper into Preston’s finances, it’s worth setting the scene as to where the club currently finds itself. North End sit 17th in the Championship at the time of writing, having drawn 10 of their first 19 games (and seven of their last nine). While the unpopular Ryan Lowe quit as manager after just one game this season, and his replacement Paul Heckingbottom has attempted to implement a style the club’s fans appear more to look more favourably upon, discontent has been building between supporters and club.

That resulted in an open letter being sent by two fan groups, PNE Online and the Preston Supporters Collective Steering Group, in late November, calling upon chairman Craig Hemmings and others in positions of power to ‘take concrete steps to revitalise the club’. Referencing Preston having been labelled ‘the most boring club in the EFL’ by onlookers, the letter called for ‘fresh ideas and a new commitment to Premier League aspirations’.

In response, Hemmings moved quickly, agreeing to an in-person meeting with representatives from the two fan groups. That took place on 2 December, lasting almost two hours, but already the potential for something good to come out of it has been severely harmed.

The supporters groups published a ‘detailed account’ of the meeting, a move that brought about ‘extreme disappointment’ from Hemmings, who released a statement to the club’s website expressing his dismay that neither he nor anyone at the club had been given opportunity to agree or disagree with the contents of said account. In return, the fan groups claimed to have acting in line with what was agreed with Hemmings at the meeting, stating their ‘surprise at Mr Hemmings’ differing interpretation’.

In other words, it’s all a bit of a mess.

Profit and loss account

Prior to 2019, Preston’s losses weren’t too large, with the club even turning a £3 million profit in 2018. Yet since then losses have piled up, totalling £91 million in the last six years. Or, in other words, the club has lost roughly £292,000 a week (pre-tax) over the last six seasons.

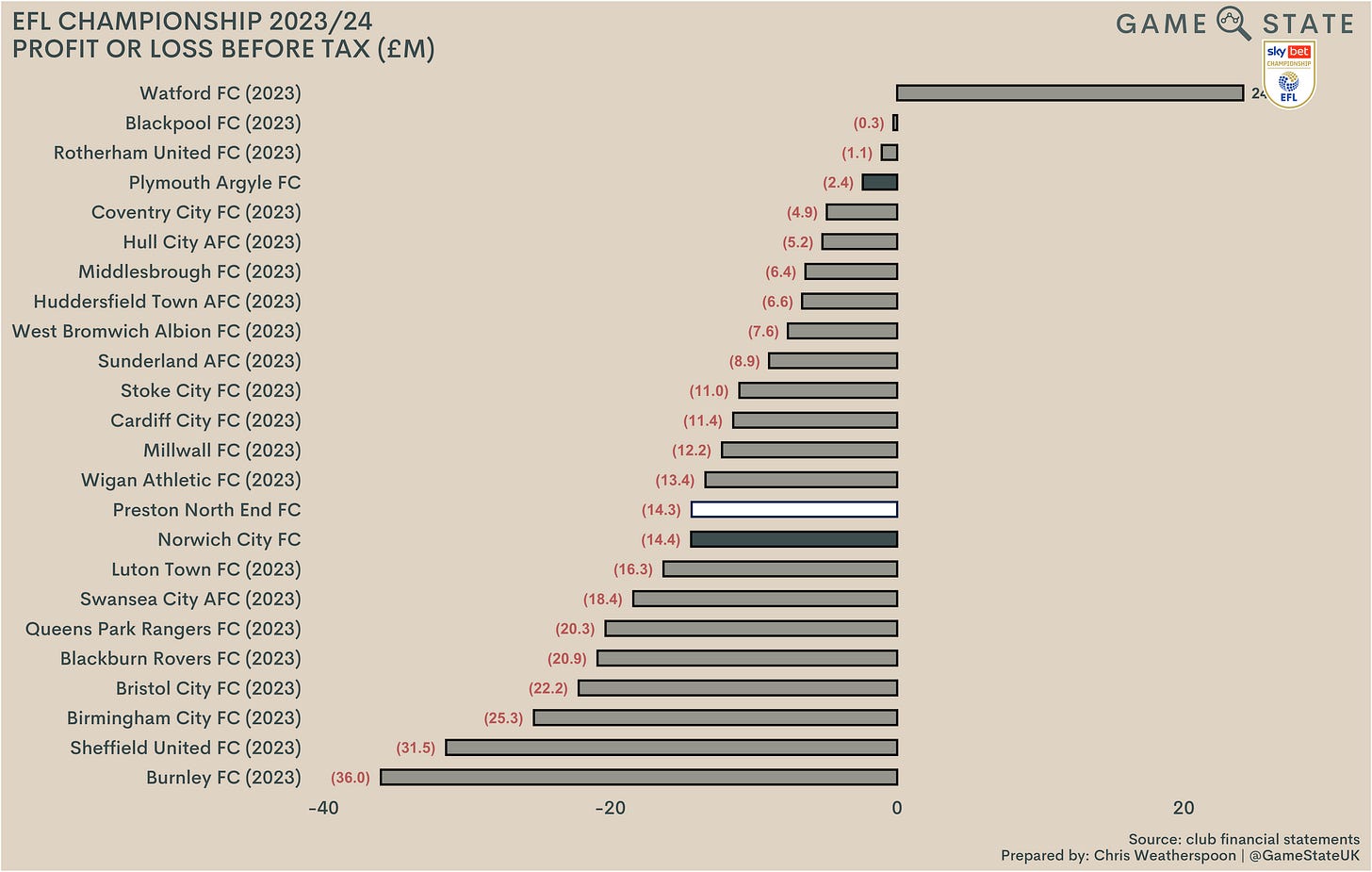

Preston are just the second Championship club to publish accounts for the 2023/24 season, though Plymouth Argyle did announce their own £2 million loss last week. North End’s £14 million deficit was pretty much the same as Norwich City’s last season, and the fact that pits those clubs in mid-table is indicative of just how financially precarious England’s second tier is.

A look at the division’s 10-year profit or loss profile makes for some bleak reading, and there are already three new red additions in the 2024 column. Just 30 Championship clubs have turned a profit since 2015, and seven of those were relegated. In all, the division has racked up £2.9 billion in losses in the last 10 years and, given we currently only have three results from last season to report on, don’t be surprised if that sum ticks past the £3 billion mark by the time all of the 2023/24 financials are published.

At the operating level, it’s more of the same story for North End, which makes sense given their general inability to derive profit from player sales (as we’ll see in greater depth later). Most clubs make a loss on a day-to-day basis, but Preston saw their operating deficit double in 2019 and then increase by almost half again in the next three years. The club has arrested the slide, and last season’s result was a half-million better than 2023, but Preston are still losing an average of £283,000 a week from day-to-day operations.

Troublingly, at least for everyone else, a £15 million operating loss for Preston was the seventh-best result in the Championship. Every club lost money at the operating level, and 14 lost more than £20 million, a damning indictment of the financial madness that swirls in England’s second tier.

Turnover

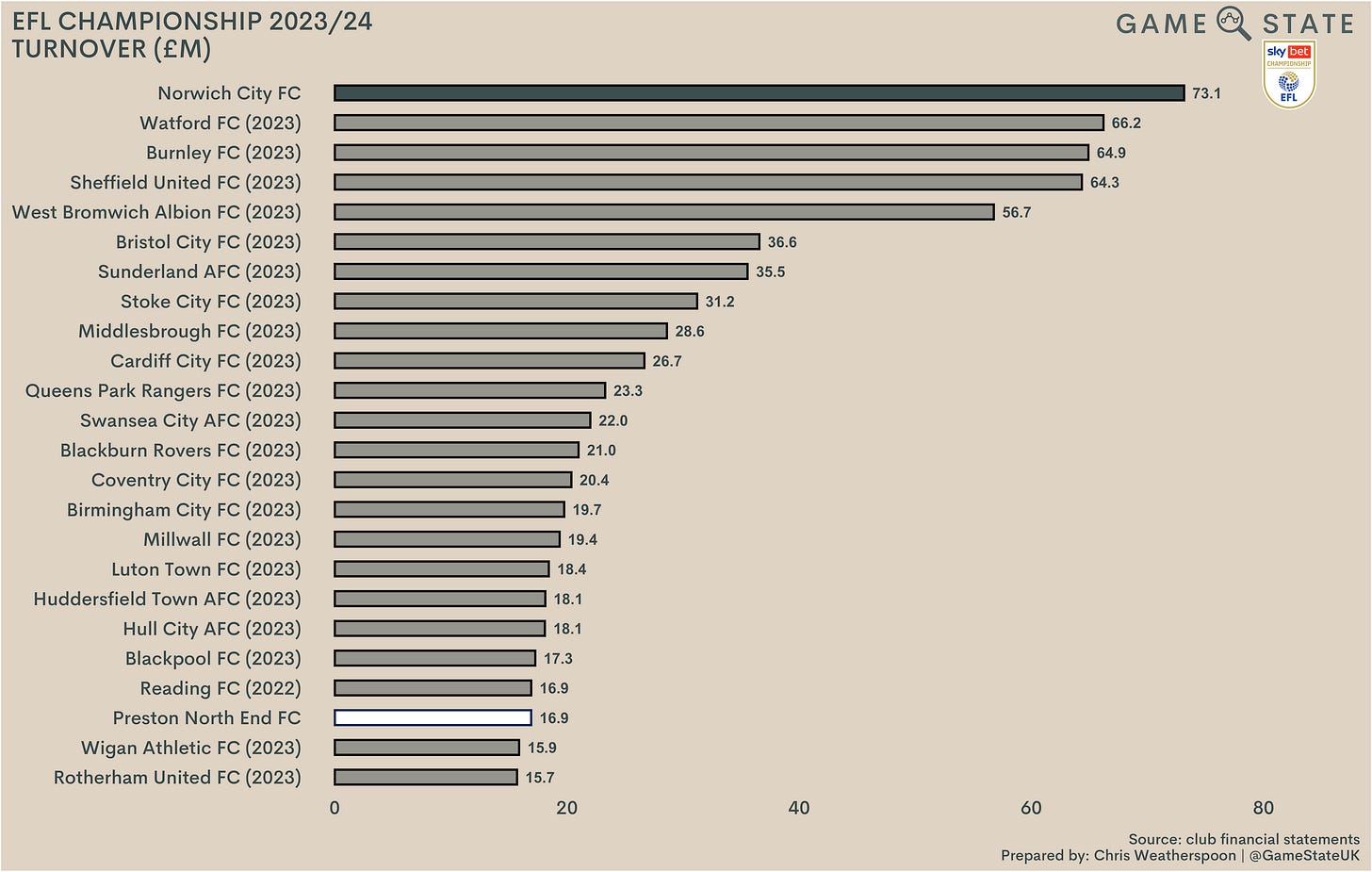

Those continued big losses came despite Preston recording club record income last season. That mark rose to £17 million, an eight per cent increase on 2023 and the fourth consecutive year or growth. As recently as their League One promotion season in 2015, North End were recording total income in the seven-figure range, so growth here is both welcome and much-needed.

In many ways, Preston’s continued presence in the Championship reflects a club punching above its weight. While £17 million turnover represented a new club record, that’s actually the third-lowest in the division based on most recent figures. Those clubs in receipt of parachute payments enjoy a sizeable advantage over the rest, as is well-known, but it’s telling that Preston’s income is also less than half the likes of Bristol City and Sunderland.

Matchday income

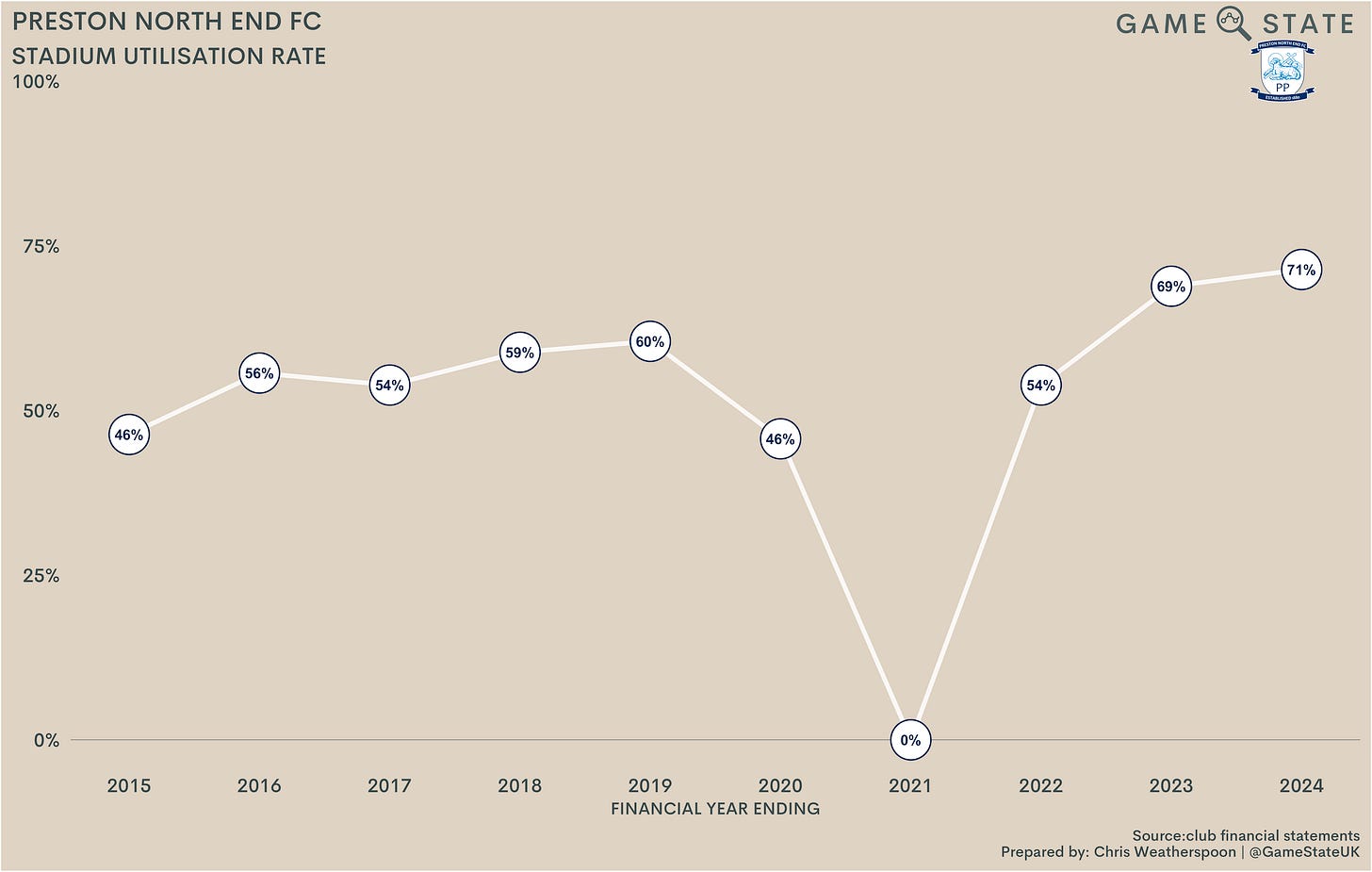

Deepdale was as full as it has been in any of the last 10 years, as the club recorded an average attendance of 16,714, a three per cent increase on a year earlier, even as the number of season ticket holders fell (albeit only by 34).

That translated to record matchday income of £4.3 million, an increase of 10 per cent from 2022/23. It’s the first time Preston’s gate income has tipped over the £4 million mark, reflecting that higher average gate, though it still works out at an average of just £11 per head across the league season.

Preston have prided themselves on offering one of the cheapest season tickets in the division - adults could pick up a season ticket last year for as low as £280 - and while it’s hard to criticise them for that it’s also true that it’s still not ensuring a full house at Deepdale, with nearly 30 per cent of the ground still empty on an average week.

Based on most recent figures, Preston’s gate receipts were the seventh-lowest in the Championship. The spread of income within the division isn’t enormous, with most clubs, Preston included, more heavily reliant on other income streams, but it’s still clear the club has work to do in boosting its matchday income. Whether they can or not remains to be seen; the most sure-fire way to increase attendances is to put together a team capable of winning promotion, something which, at least in Preston’s case, will probably cost more than the immediate benefits the club would see at the turnstile.

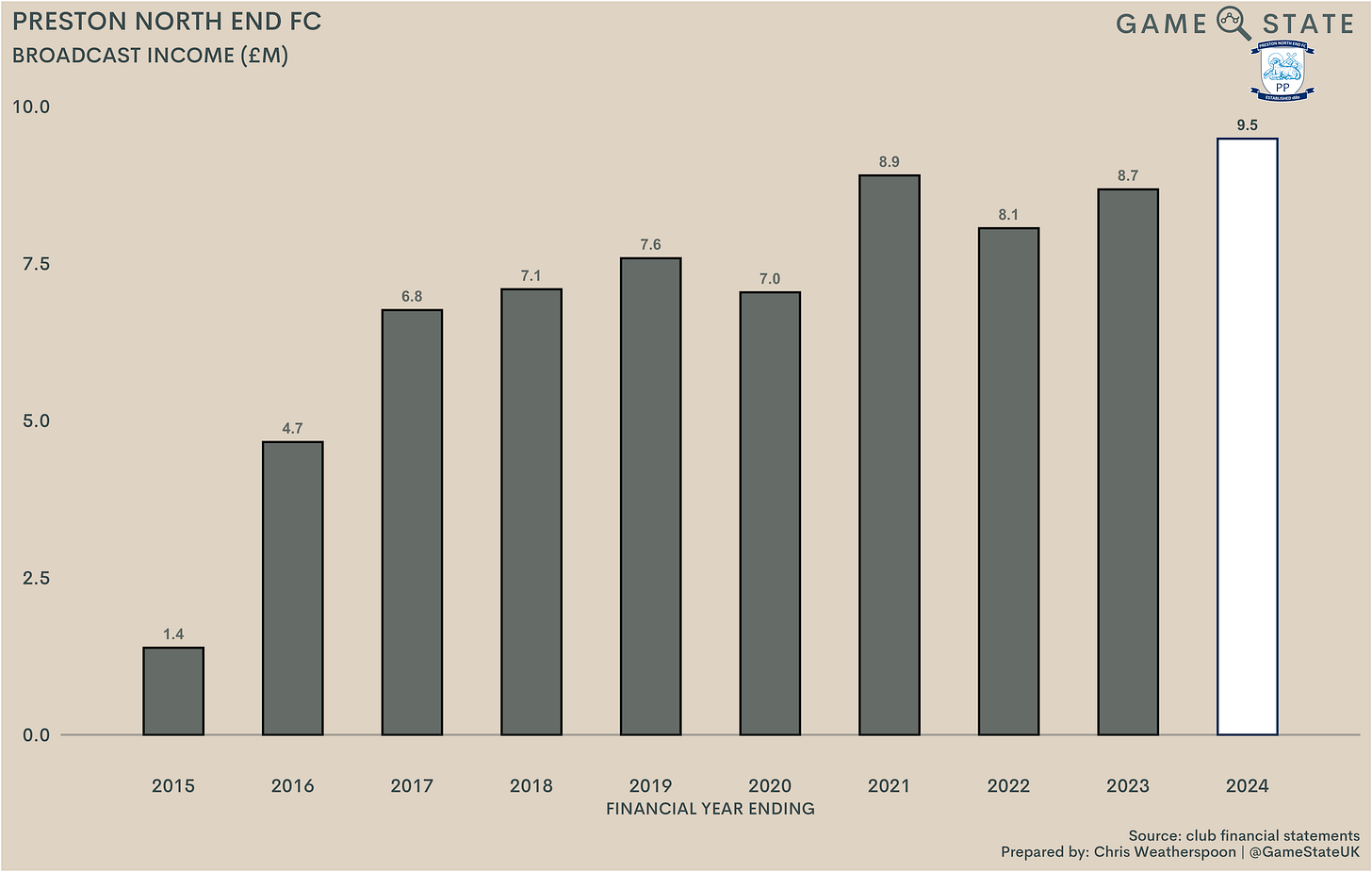

Broadcast income

Preston’s largest income came from TV money, hitting a new high of £9.5 million last year. That was driven by an increase in EFL and EPL distributions, with the latter ticking over £5 million for the first time. Preston’s broadcast income has now doubled from their first season back in the Championship in 2016, reflecting the growth in the EFL’s TV deal across that time. This season, with the 2024-29 TV cycle in its first year, will see this figure increase again, and the club should clear the £11 million mark.

Parachute payment clubs aside, broadcast revenues are much of a muchness. Clubs that make the play-offs tend to earn a bit more than others due to the attractiveness of televising those matches, and the only other realistic way to increase this stream is to undertake a strong run in domestic cup competitions. Preston failed miserably at that last season, exiting both the FA Cup and the Carabao Cup at the first hurdle.

Since returning to the second tier, North End’s largest revenue stream has consistently been income from TV, reaching as high as 75 per cent in the Covid-hit 2020/21 season. The proportion of broadcast revenue to total income has stabilised at the 56 per cent mark, which isn’t unique among Championship clubs, but does speak to the work Preston have to do - and should be doing - when it comes to revenue generation. Currently over half their income is guaranteed as soon as they retain Championship status for the coming season, so a more proactive approach to boosting other revenue streams would be welcome.

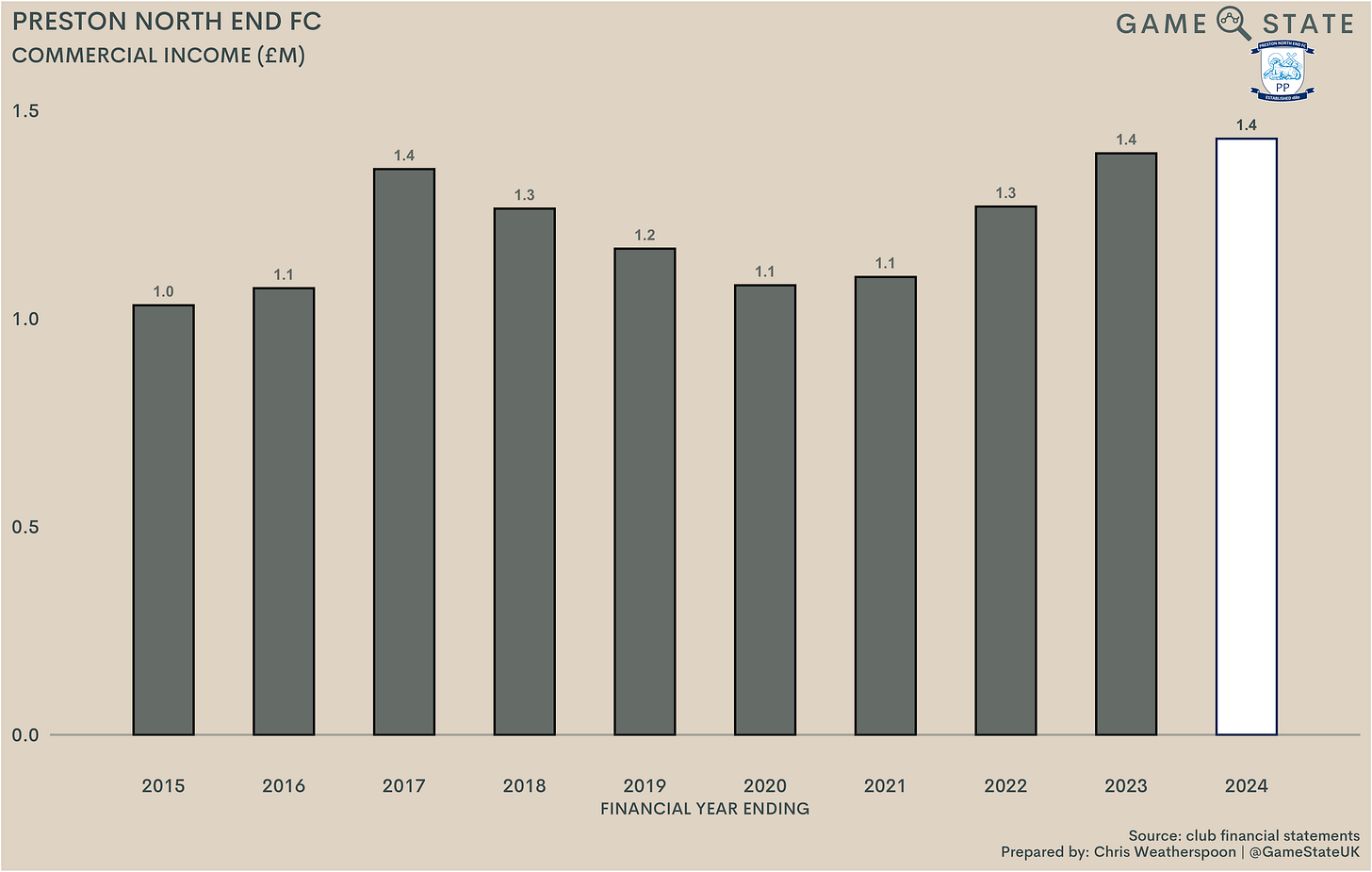

Commercial income

By far the most disappointing revenue stream for The Lilywhites is in commercial, where the club still earns just over the £1 million mark. The figure has been on the rise in the last four years but it’s still miserly, and it would be even if we included the £1.5 million in rental income Preston receives each year (it has been categorised here within ‘Other income’).

Indeed, Preston’s commercial income is the lowest in the second tier, which is a damning result given the club has long solidified itself in the division. Even if we re-categorised that rental income, they’d still be in the bottom five, which is troubling when you see the names of some of the clubs above them.

North End were of course the first ever league champions in English football, and though the club’s glory days are a long way behind them it seems strange that their marketing offer remains so ineffective, especially given the club has long consolidated itself in the Championship. Given their continued over-performance against their wage bill, it’s hard not to wonder how much better the club could have fared in recent years had they generated a little more of their own money to improve the playing squad.

Even if we were to include rental income, Preston’s commercial revenues would remain in the league’s bottom five. North End made just £160,000 from merchandise last season, a sum that wouldn’t be out of place in lower divisions. Meanwhile, the front-of-shirt sponsorship deal inked with PAR Group in 2021 has pushed sponsorship revenues over the £1 million mark (other deals are included within this figure too), but it still represents the very low end of what Championship clubs can earn commercially.

PAR, a manufacturer, were retained as the club’s principal sponsor for the 2024/25 season, though Preston would be foolish not to re-assess the deal at the end of the season. The new EFL broadcast deal gives Championship clubs more exposure than ever before, and the likes of Preston should be looking to maximise their commercial revenues on the back of it.

Wages

After a reduction in 2023, Preston’s wage bill was up a smidge (two per cent) to £22 million, although the bulk of that increase came in non-football wages. The clubs playing and football management wage bill remained just about static at £18.7 million; Preston are one of just a handful of English clubs to publish football staff wage figures.

That’s currently the fifth-lowest wage bill in the Championship, albeit half the division operate in the £22-28 million range. Preston operating at the low end of that range and never really being troubled by relegation in recent years is testament to them getting the most out of their squad, though the names of those clubs below them could prove ominous. Huddersfield Town, Blackpool and Rotherham United have all recently been relegated to League One, showing how difficult it is to compete when other clubs pay their squads more.

Plotting Championship wages against points per game across the last decade helps highlight that over-performance. In each of the last nine seasons, Preston’s wage bill has been below average for the division, yet in each of those seasons the club has managed to perform averagely or better. Unfortunately, it does also lay bear just how much it is costing clubs in wages to achieve promoted.

Comparing Preston’s wage bill to their league finishes across their Championship years highlights just how much the club has consistently punched above its weight. In each of the eight seasons to the end of 2022/23, North End’s league position exceeded where they’d be expected to finish based on wages alone.

In their first three seasons that over-performance was huge, and it was still significant recently, as they finished 12th in 2023 with the 19th-highest (or sixth-lowest) wage bill in the division. There’s insufficient data to determine where their wage bill ranked in 2024, but it’s a safe bet Preston over-performed again last season in finishing 10th.

Despite that over-performance, the economics of English football are such that Preston have routinely had to spend way more on wages than any sane business would. In each of their Championship years, wages have exceeded revenue, and during the pandemic the club spent nearly double its entire income on wages alone.

Last season saw a fourth annual fall in this metric, yet Preston still spent 130 per cent of their turnover on wages. In other words, before the club had paid for a single lightbulb to be turned on, they’d already promised away their entire annual income and nearly a third more besides on staffing costs.

Preston aren’t alone in spending more than their turnover on wages, as half the Championship did so based on latest figures. Yet theirs remains at the higher end and, ultimately, just because everyone else is doing it doesn’t make it wise. The directors are frank about the situation in the latest set of accounts, stating that ‘Operating cash flow continues to be adverse as the club has contracted a squad with wages which are high in comparison to its revenue’. The problem is how they go about fixing that without weakening a squad that is already over-performing.

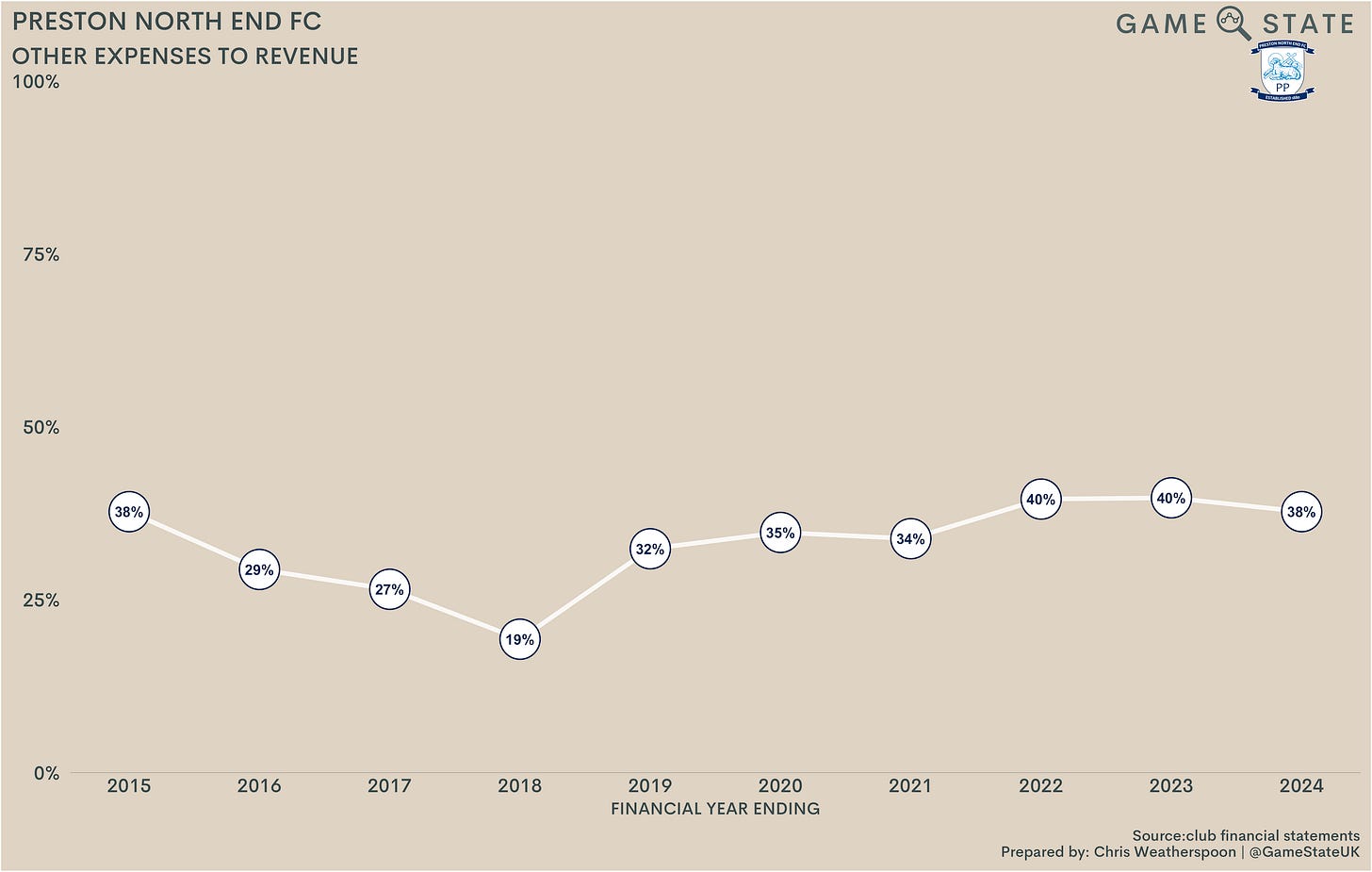

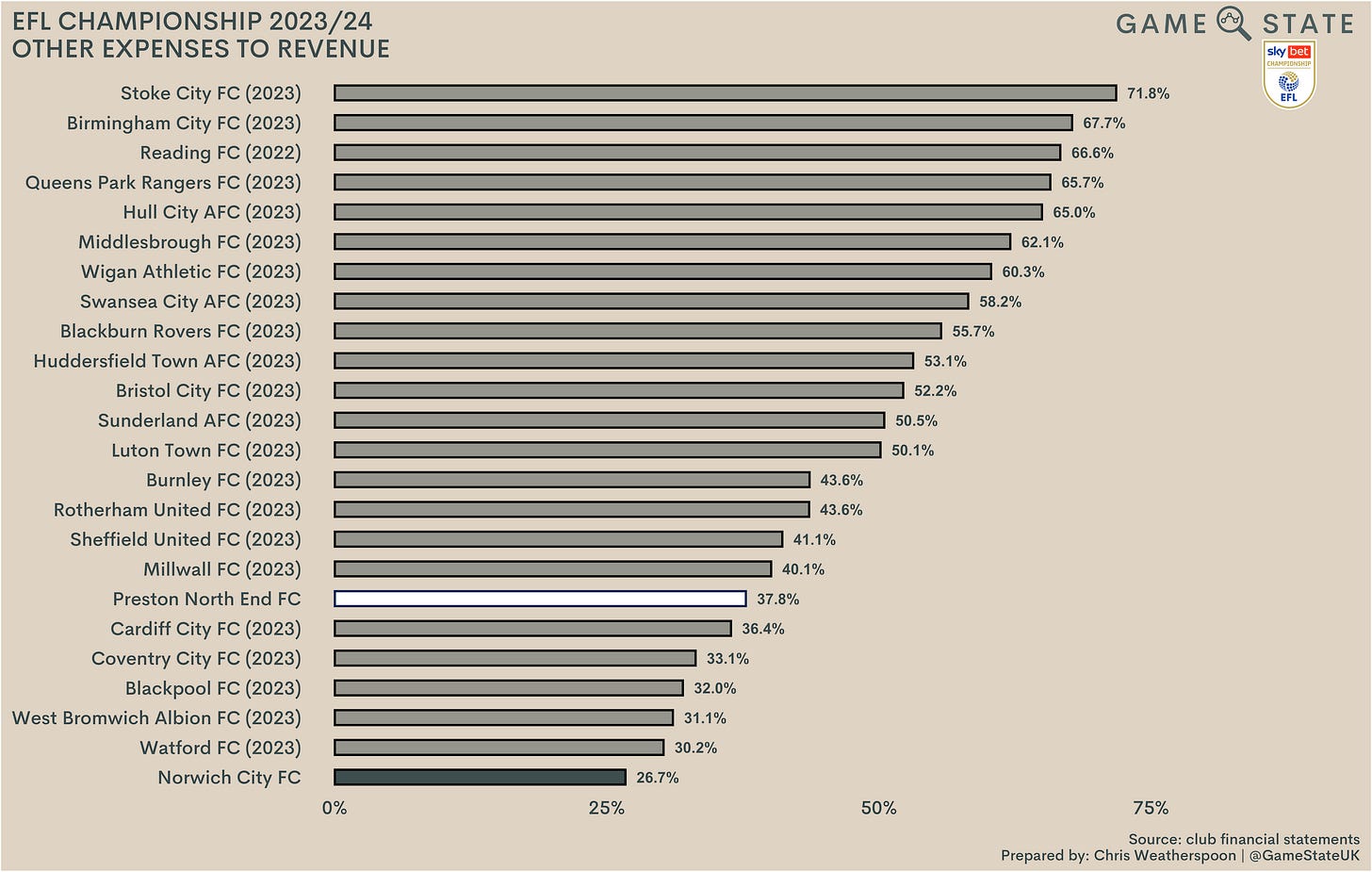

Other expenses

Preston’s other expenses (essentially, non-staff costs excluding depreciation) were up to their own club record, rising three per cent on prior year. That’s a pretty modest rise, particularly given some of the increases seen elsewhere, and inflation in the wider economy accounts for much of the uptick.

North End’s other expenses are actually some of the lowest in the division, with only Blackpool’s lower based on most recent figures. That’s just as well given that huge wages to turnover figure, and the size (or lack thereof) of Preston’s expenditure here reflects the size of the club and its activities. Over half the division currently spends more than double on non-staff costs, and a handful spend significantly more than that.

After an increase in 2022, Preston’s other expenses as a proportion of revenue have stabilised around the 40 per cent mark, though did drop a touch last year as a result of that club record turnover. That shows good cost control, though it’s notable that the relative surge in these costs in 2019 coincided with the start of those eight-figure losses.

Set against their peers, Preston are again near the bottom end when it comes to other expenses as a proportion of revenue, with several clubs spending more than half their income here. That, combined with high wages bills, helps explain why Preston’s own losses are nowhere close to the biggest in the Championship.

Player trading

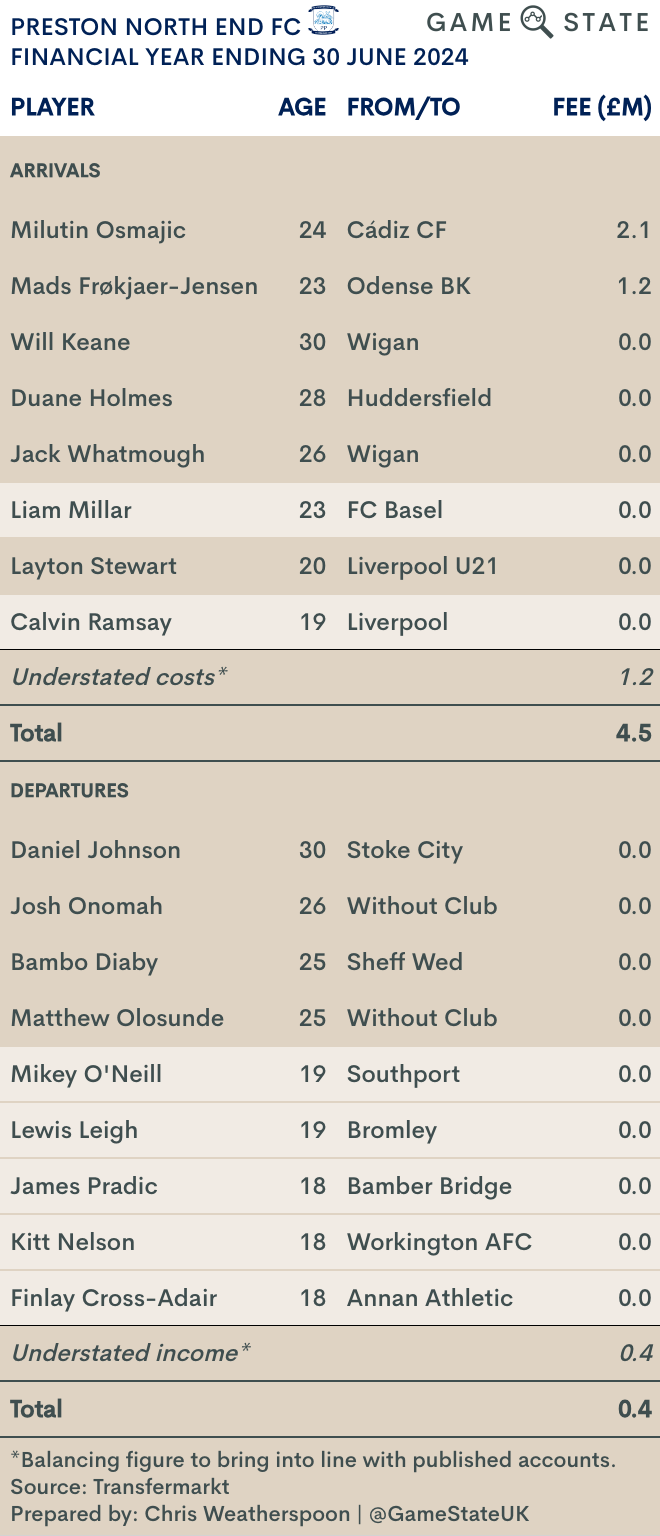

2023/24 represented a year of pushing the boat in relative terms when it came to player trading, as Preston’s net spend of over £4 million was their highest since 2019. In the last decade, Preston’s net transfer spend has been just £6 million, so last season really did mark a shift for the club. Figures post-30 June 2024 haven’t been disclosed in the club accounts, but based on reporting it seems North End’s net spend was positive again this summer.

In what may be a surprise to some fans, that £4 million represented one of the highest net transfer spends in the Championship as a proportion of income. In fact, were it not for Burnley’s 31 July accounting date, it would be the highest proportional spend in the division based on most recent figures, as bulk of The Claret’s purchases in their 2023 financial year came following promotion and in the hope of building a team capable of retaining Premier League status.

£4 million doesn’t really register as big spending in football these days, but for Preston it represented nearly a quarter of the club's income last season. That’s a big proportion for a Championship club, and though the amounts are all relative it does provide some sympathy to an ownership who’ve been accused of being happy to sit in mid-table.

Last season’s spending primarily went on Milutin Osmajic, Mads Frøkjaer-Jensen and Will Keane (Keane's fee was undisclosed, but likely comprises the bulk of the ‘understated costs’ figure detailed below). All three were first-team regulars, with Keane and Osmajic ending up as Preston’s top scorers, bagging 13 and eight goals respectively across the year.

Preston’s £5 million gross spend propelled them into mid-table, though it was nearly three times lower than spending at MIddlesbrough (Burnley’s whopping figure is misleading, for reasons outlined already). Still, there was clear intent to push the club on last season, though some fans might rightly argue that this is only redressing the balance after years of spending very little on fees.

One area Preston have notably struggled with for a long time is in player sales, generally struggling to entice other clubs into parting with big sums for players. Two of the clubs four largest ever sales remain David Nugent and Jon Macken, strikers who left the club 16 and 22 years ago. It was much the same story last season, as North End failed to earn even half a million pounds on outgoings.

Correspondingly, profit on player sales was low too, as it generally has been at the club. The exceptions came with the departures of Jordan Hugill (to West Ham United) in 2018 and Callum Robinson (Sheffield United) in 2020, but both of those were one-offs rather than signs of a reliable revenue stream for Preston. Miserly player sales are the reason why Preston’s operating losses have generally tracking to overall deficits, whereas other Championship clubs increasingly rely on player profits to offset their day-to-day losses.

Indeed, Preston’s £0.4 million profit on players last year was one of the division’s lowest. Watford’s division-leading £59 million is something of an outlier given they were able to sell players who had shown their ability to cope in the Premier League, and while relegated clubs enjoy the bulk of Championship player sales it isn’t the case that they’re the only ones who can rely on player trading. Bristol City have long been strong sellers, as were Brentford before their promotion in 2021. One issue facing Preston is their academy setup; North End’s academy is Category Three, so the club struggles to bring its own stars through to then sell for big money, a matter not helped by the presence of talent factories less than an hour’s drive away in both Merseyside and Manchester.

Across the last decade, Preston have banked only £22 million in profit from player sales, and over two-thirds of that came from those sales of Hugill and Robinson. Unsurprisingly, that ranks them way down the list of Championship clubs, and well behind those at the top of the selling tree in the division.

Despite that increased spend, the impact on the club’s annual loss was unmoved, with player amortisation totalling a little over £2 million. Osmajic and Frøkjaer-Jensen each signed on four-year deals, spreading their large transfer fees (at least in relative terms) across a decent timespan.

Player amortisation costs at relegated clubs dwarf the rest of the Championship, the natural byproduct of players bought while in the Premier League remaining on club books. Amortisation charges across the rest of the division are much of a muchness, but Preston still find themselves at the lower end, perhaps not surprising given the already hefty hit to the profit and loss account incurred by the club’s wage bill.

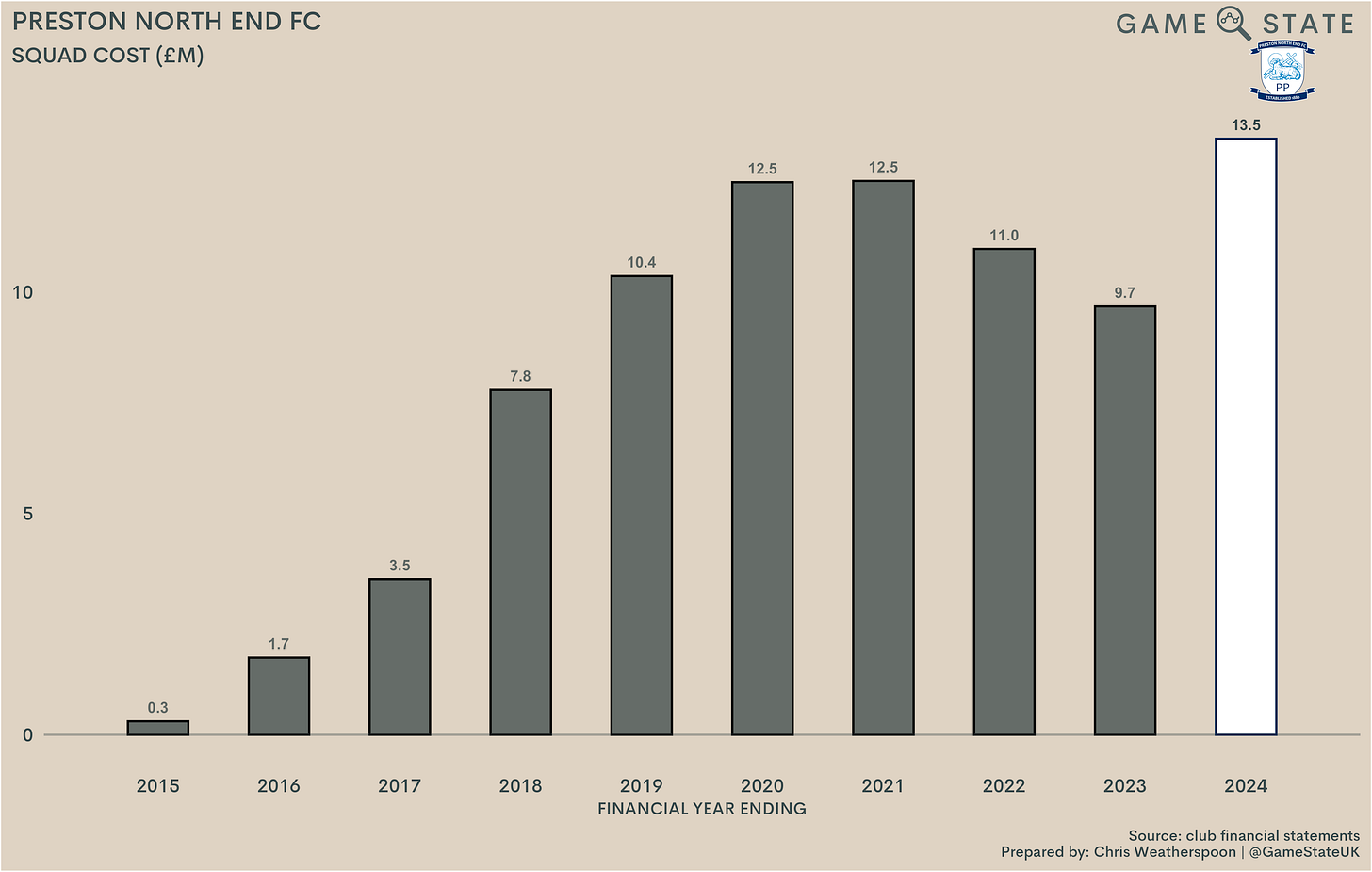

Squad cost

Another club record arrived at the end of last summer, as Preston’s squad cost ticked up to £14 million as a result of their transfer activity. That surpassed the previous high of 2020 and 2021.

That pitched them perfectly in mid-table, though it should be noted this figure is as at the end of the 2024 financial year (i.e. the end of June 2024). Here again we can see a narrow spread of values across the middle of the division, with Preston’s spend last season propelling them several spots higher than where they were previously. It wouldn’t be a surprise if they dropped down a number of spots once all of last season’s financials are released.

Balance sheet

Football debt

In line with that historically minimal transfer spending, Preston’s transfer balance - amounts owed by clubs less amounts owed to clubs - has been either positive or pretty close to zero. On the back of last year’s spending the club owed a net £2 million to others at the end of June 2024.

Not all Championship clubs disclose transfer receivables and debts but, in relative terms, Preston’s £2 million transfer debt is one of the poorer situations in the division. That’s because clubs have, in recent years, increasingly turned to player sales as a way of bolstering their underlying profitability (or, more accurately, at least reducing their losses a bit), something Preston haven’t managed.

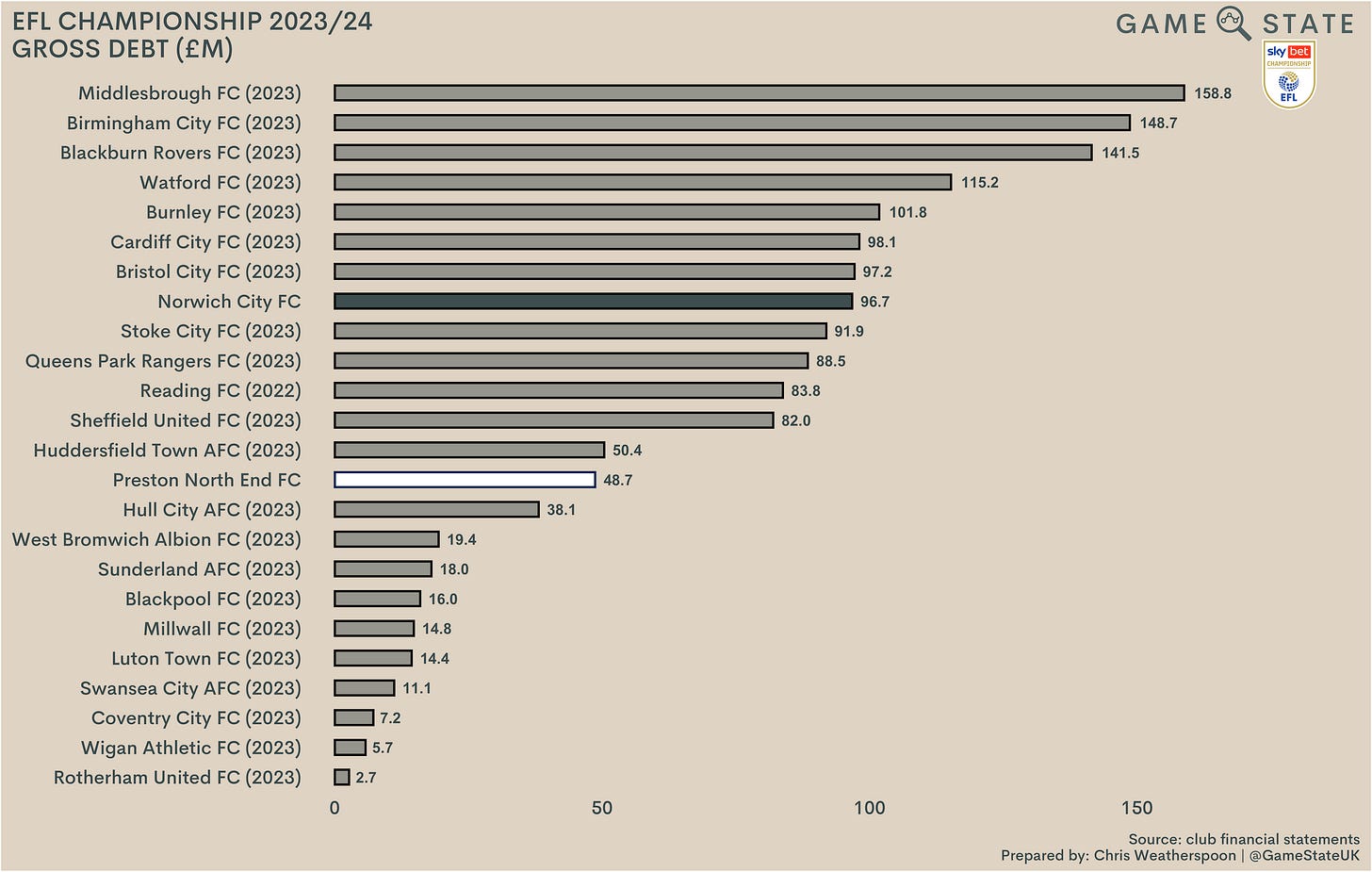

Financial debt

A significant change in the year related to the club’s debt, which had been zooming upwards in recent years. That’s a byproduct of the significant owner funding that has been required to underwrite those hefty annual losses, and Preston’s debt would have been higher again had the ownership not converted £50 million of those outstanding loans to equity last season. That took gross debt down to £49 million; in effect, the share issue capitalised all loans received by the club in the last half-decade.

Notably, those loans incurred no interest, as benevolent owners loaned the club money free of the costs that would come alongside obtaining, for example, a commercial loan from a bank. This isn’t uncommon in the Championship, as most clubs receive owner inputs with no interest burdens attached, but it still speaks to the generosity (or, if you’re so inclined, insanity) of those in charge.

Of interest to Preston and a few others will be what happens in the league above them. Recent arguments have erupted around the topic of interest-free shareholder loans, and whether clubs should have to record a market rate of interest in their Profit and Sustainability (PSR) calculations. If that came to pass and cascaded down to the Championship, Preston’s ability to comply with PSR would be adversely affected - though less so than if the ownership hadn’t undertaken that £50 million conversion.

Several Championship clubs were carrying over £100 million in debt at last check, though division-leading Middlesbrough have since seen a majority of theirs also converted to equity. Preston’s £50 million debt therefore sits in the lower mid-table range, but in truth the main issue with debt is whether or not clubs can service it. Preston have no issues in that regard, as the Hemmings family charges the club no interest; problems would instead come if the family found themselves unable to continue funding the club year after year.

Cash flow

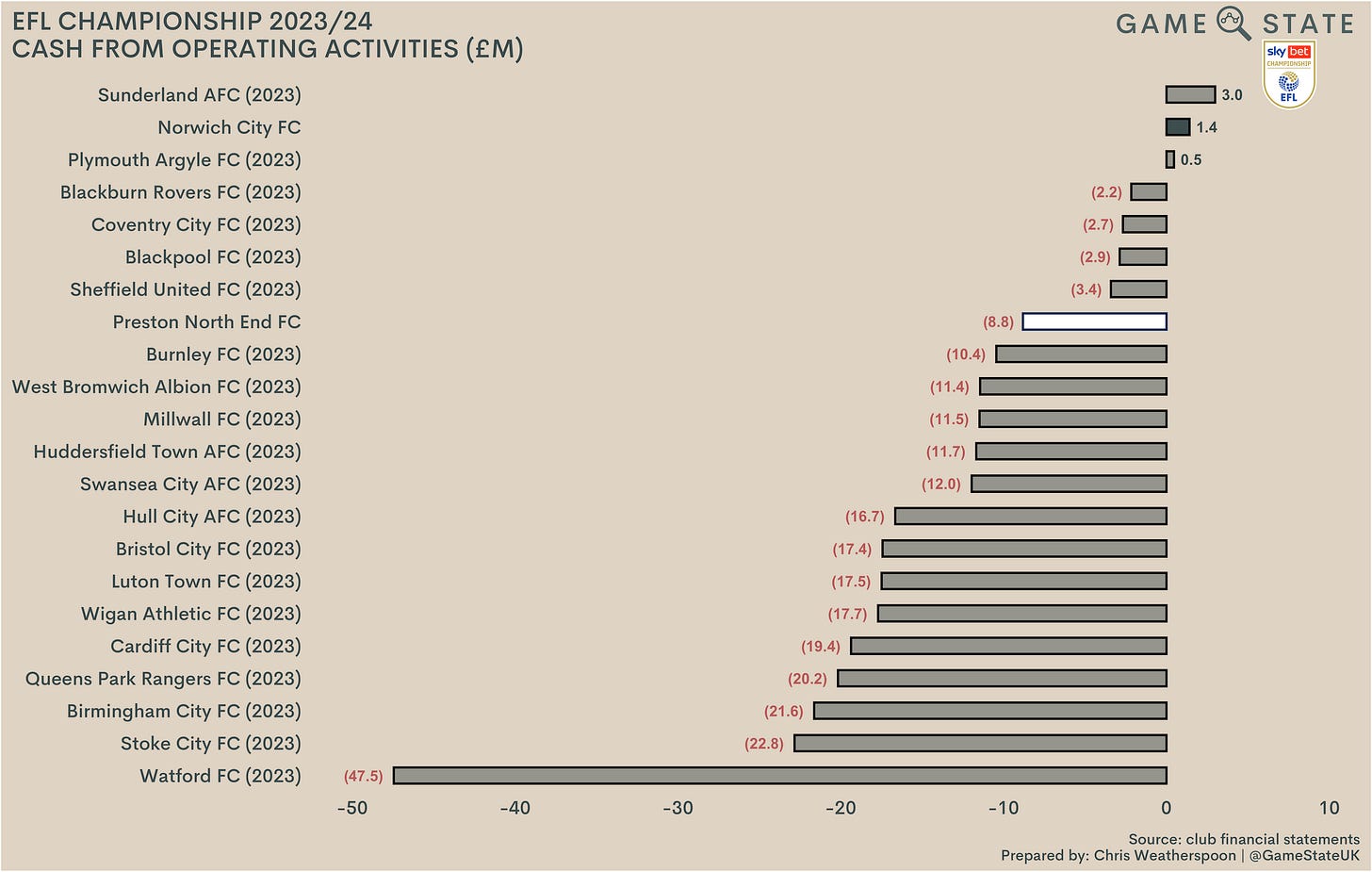

Unsurprisingly, and as acknowledged by the club’s directors themselves, Preston’s expenditure far exceeding income means the club routinely makes a cash loss from its operations. That’s another figure which appears to have stabilised following a sharp drop five or six years ago, but it still amounts to a cash loss of £9 million a season. In the last decade, North End’s cash outflows from operating activities stand at £68 million.

Despite that, it was one of the better results in the division. Only three clubs were cash flow-positive (Rotherham United likely were too, but don’t disclose their cash flow statement), while 14 different clubs posted operating cash flow deficits greater than £10 million.

Over the last decade, Preston have received cash inflows of £82 million, split £50 million share capital and £32 million in net loans. In turn, that £82 million has been spent on:

£68 million covering operating losses;

£8 million capital expenditure;

£5 million net player trading; and

£1 million increase in cash balance.

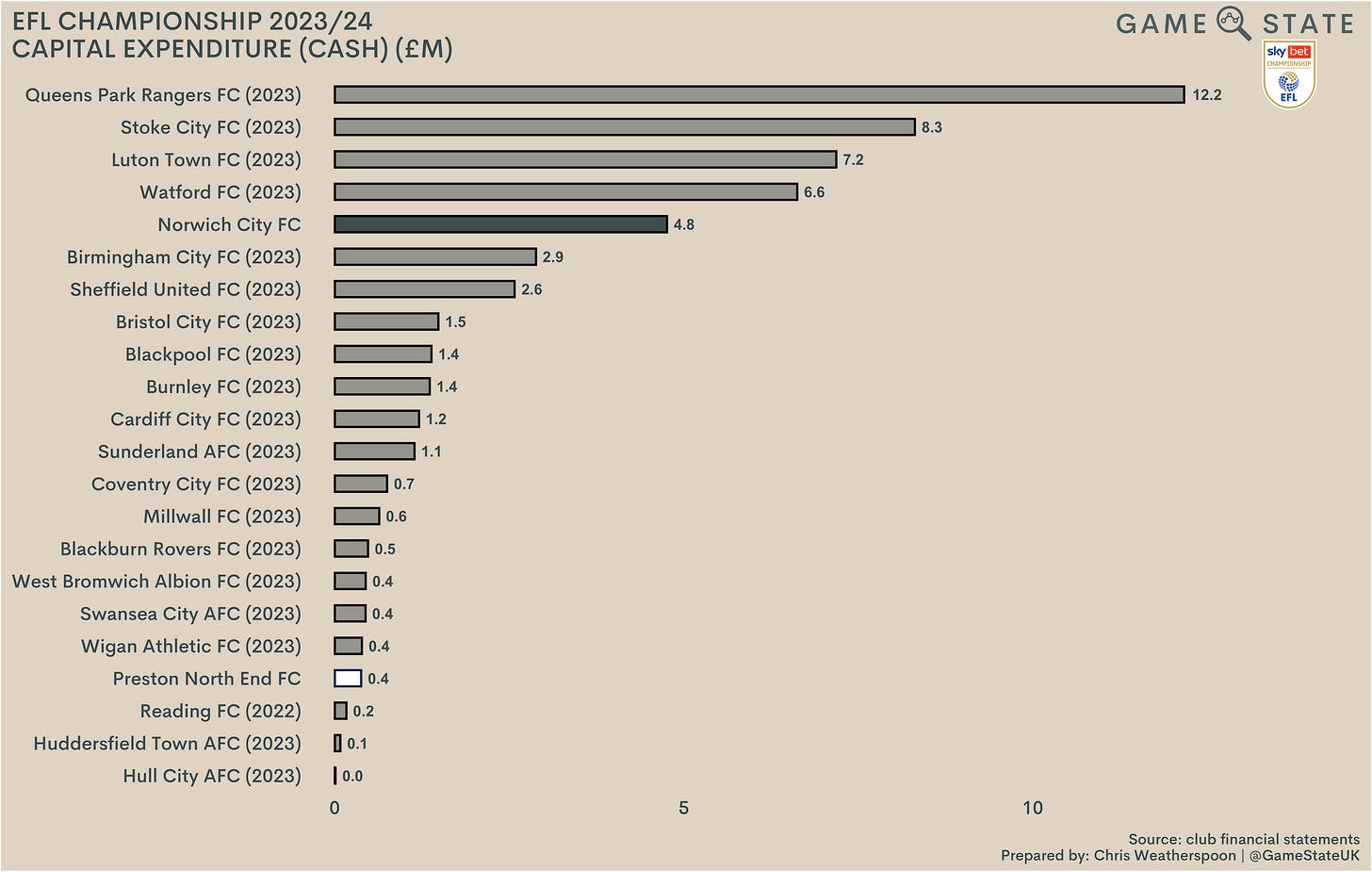

North End have committed just £8 million to capital expenditure in the last decade, which isn’t all that surprising given the already hefty burden that has fallen on the shoulders of the Hemmings family.

The lack of spending on infrastructure was one of the topics discussed in that meeting between Craig Hemmings and fan group representatives, where the chairman tacitly admitted choices had to be made between funding the playing squad or off-field matters.

Per that (disputed) detailed account of the meeting, Hemmings ‘was keen to advise that whilst stadium infrastructure costs are not part of FFP, it all comes from one budget, so any spending on areas such as the Town End roof or Floodlights has to be balanced against strengthening the team.’

In truth, the same is true of many Championship clubs. Faced with swingeing losses, clubs focus their resources on trying to get promoted, with little left over for what chairmen and owners might quietly term as the ‘nice-to-haves’. Exceptions tend to come in the instance of big, one-off projects, like QPR’s recent move to a new training ground.

Owner funding

Facing a winding up order, Preston North End were saved from potential ruin by Trevor Hemmings in June 2010, when his £470,000 loan to the club allowed them to pay off a debt owed to HMRC. Hemmings acquired the club through holding company Deepdale PNE Holdings, which is in turn owned by Wordon Limited, a vehicle that Hemmings controlled.

Hemmings’ death in 2021 saw ownership of Wordon pass to his estate and, in September 2023, settlement of the estate saw shares in Wordon then pass to a discretionary trust, the trustees of which are members of the Hemmings family. Trevor’s son Craig now chairs the club, and there’s been no let-up when it comes to the family funding North End since the senior Hemmings’ passing three years ago.

Last season marked the fourth year running the club has received over £10 million in funding from shareholders, a necessary result of those continued annual losses. Without the Hemmings family’s continued financial support, Preston would not be able to survive in the second tier.

Across the last decade, the Hemmings family has provided the club with just about all of its external funding, totalling £81 million since the 2014/15 season. That’s a lot, but still only around mid-table for Championship clubs in that time. There are some nuances to this, as several clubs in the list below received owner funding while in other divisions (Sunderland’s £93 million, for example, was mostly received while in the Premier League), but it’s still the case that the Hemmings family has committed significant sums simply for The Lilywhites to keep their heads above water in the second tier.

Profit and Sustainability Rules (PSR)

Preston have lost £49 million pre-tax in the past three years alone, which immediately sets hares racing when it comes to PSR compliance. Championship clubs can lose up to £13 million a season provided owners contribute ‘secure funding’ to club coffers, but across three seasons that amounts to £39 million - or £10 million less than North End’s pre-tax losses in that time.

Of course, that’s without considering the deductions the club can make for what the EFL deems ‘good’ or allowable expenditure. We can deduce the club’s depreciation charge on its fixed assets from the financial statements, though there’s significant guesswork involved in ascertaining the quantum of other allowable costs.

Per Game State’s PSR model, we estimate Preston were just about under the £39 million loss limit to the end of last season; without the £50 million conversion of loans to shares - which constitutes secure funding - North End would have failed to comply.

Looking ahead to the end of the current season, Game State’s PSR model estimates that Preston could lose £21 million pre-tax in 2024/25 and still comply with EFL rules. Again, these are very much estimated figures, but the broader message remains accurate: Preston already lose £14 million a season, and any increase on that figure will push them closer to non-compliance.

The future

PSR-compliant or otherwise, it’s difficult to see how anyone involved with Preston could be happy with things remaining as they are ad infinitum. Fans are bored and restless; the Hemmings family have to part with a hefty wad of cash each and every year to basically stand still.

Indeed, one of the main topics discussed in that meeting between Craig Hemmings and fan representatives was the sustainability - or lack thereof - of the club:

Though the chairman denied that the family demanded a certain level of investment, it wouldn’t be the worst thing if any future owner of Preston North End was able to commit to a chunky annual sum. At the moment the club’s ownership is spending over £10 million a season and seeing little in return other than consolidation; now, after years of that, fans are (perhaps rightly) growing restless.

The summer’s transfer activity marked another positive net spend, with Jeppe Okkels and Stefán Teitur Thórdarson joining for fees, while Preston appear to have received nothing for any outgoings. Neither of those two new signings have made themselves ever-presents as yet, and Okkels has played scarcely over 100 Championship minutes at the time of writing. The best signing to date looks to be the loan of Leeds United’s Sam Greenwood, whose six goals so far this season are the most at the club.

The mood around the club wasn’t helped by the fact many fans felt an opportunity to finally reach the Championship play-offs was blown at the end of last season, with Hemmings himself said to be annoyed some players told the media there was “nothing to play for” as the season wound to a close. The replacement of Lowe with Heckingbottom seems to have been met with general approval, though results nor performances have really followed suit. 19 games into the season, North End sit 12 points away from a play-off berth but just two above the relegation zone.

Preston North End, through little fault of their own, are a product of the lack of financial regulation in English football. As the money in the Premier League has grown and grown, clubs in the division below have mired themselves in increasingly deeper debts and losses in a bid to join the party. That has pushed the average wage bill in the Championship up to the point where half the division spends more than its annual income on wages alone.

That Preston have done that every year for a decade might seem irresponsible on face value, but in many ways it’s hard to know what else the club could do, at least from the perspective of wage spending. North End have outperformed their wage bill for nine consecutive years; a more valid criticism of the club would be the failure to improve revenue streams.

That’s particularly the case when it comes to Preston’s commercial offering, which generates income so low as to be a valid source of embarrassment. Gate receipts could improve too, though that probably goes hand in hand with building a squad capable of doing more than just repeatedly finishing in mid-table.

The Hemmings family’s commitment to Preston for more than a decade has been clear, funding the club to the tune of eight figures a year and expecting neither interest nor repayments in return. Even among the current acrimony, fans have been repeatedly careful to ensure their appreciation of that commitment is noted and known; without it, who knows where the club would be right now.

Yet sizeable annual funding does not leave the ownership free from fair critique. Preston’s fans feel like the club is pretty much just surviving in the Championship for the sake of it, a view that is shared by plenty of outsiders.

The club has proven itself capable of over-performing its budget time and again, but to what end?