Club financial analysis: Norwich City FC 2023/24

Game State's analysis of Norwich City FC's 2023/24 financial results.

As they enter their third successive season back in the EFL Championship, Norwich City’s recent yo-yoing between England’s top two tiers has been firmly halted, though 2023/24 did see the Canaries improve to a sixth-placed finish, seven spots higher than a year earlier. That was enough to earn them a play-off berth, though dreams of an English Premier League (EPL) return were dashed inside 40 chastening Elland Road minutes in the semi-final second leg, with hosts Leeds United eventually running out 4-0 winners.

Norwich will hope the current season brings greater fortune, but one area they’ve come in top of the Championship pile - and second in England - is in releasing last season’s accounts. The Carrow Road outfit are frequently once of the earliest clubs to publish their financials, and this time was no different, with the club unveiling their 2024 accounts on Friday 18 October.

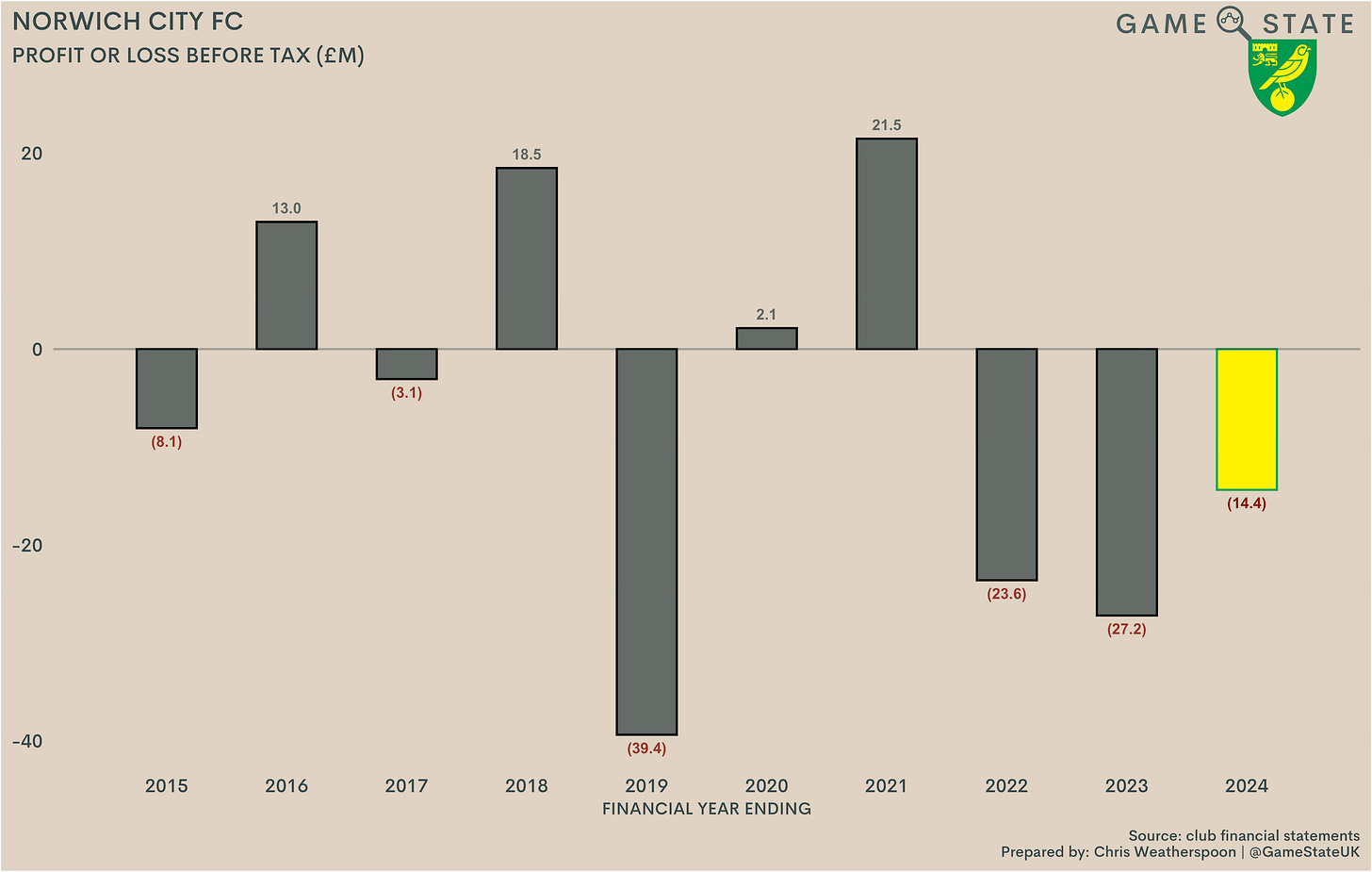

Those accounts revealed a £14 million loss for 2023/24, almost half their deficit of 2022/23. That’s impressive given the club’s income was always going to drop, in line with the anticipated fall in EPL parachute payments between year one and year two.

Norwich offset that income drop in two ways. First, by booking £10 million more in player sale profits than in 2023; second, by bringing down squad costs, reducing the club’s wage bill by eight per cent and the cost of transfer fee amortisation by 22 per cent. The £18 million combined positive effect of those improvements proved plenty in combatting the income drop-off and small increases in non-staff and interest costs.

What’s more, that income drop wasn’t as pronounced as might have been expected. While Norwich’s parachute payment fell by an estimated £9 million, the drop in the club’s total broadcast income was just £4 million. Moreover, the club improved its take from gate receipts, which again helped to limit the club’s annual loss.

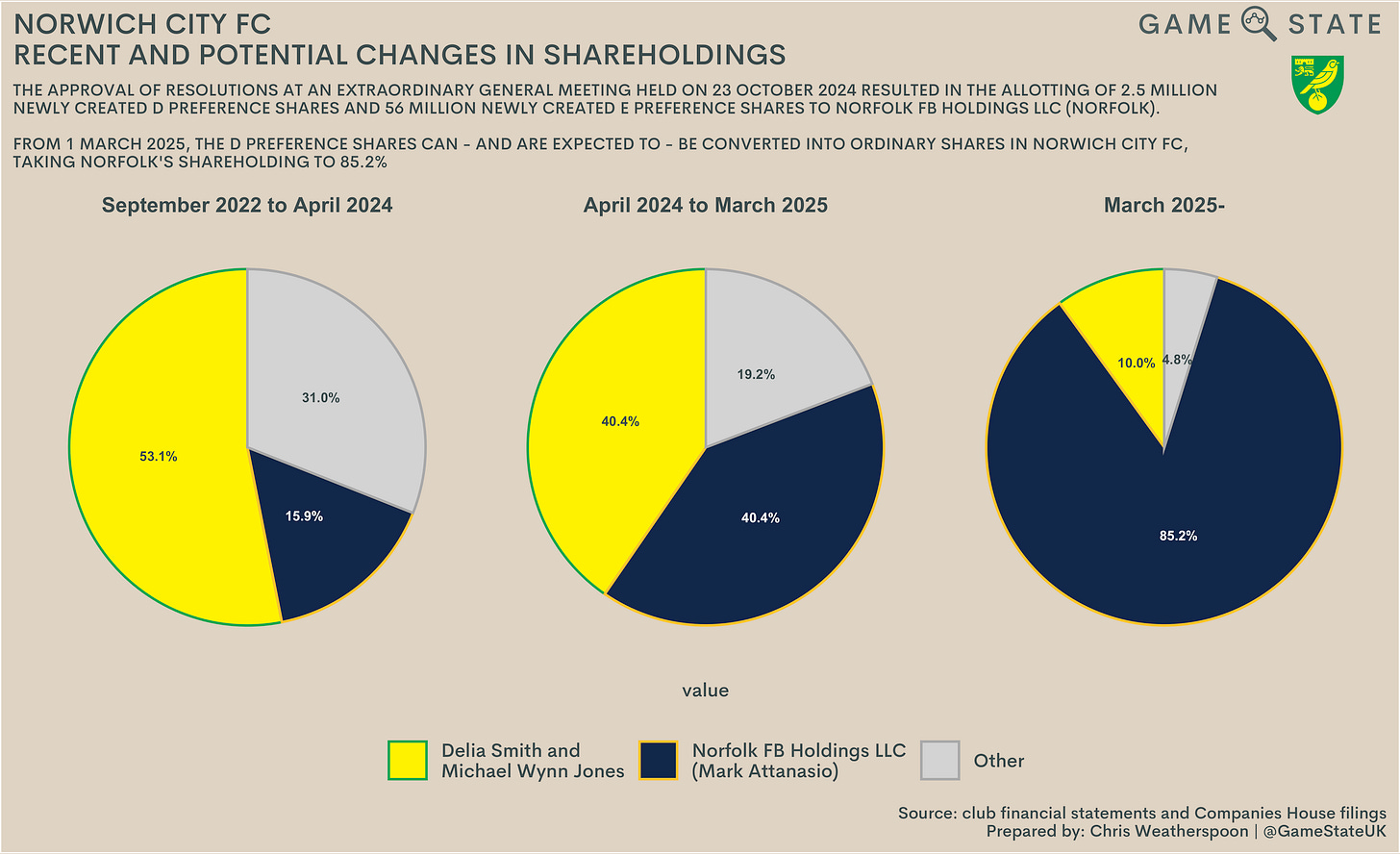

Ownership changes

Before delving any further into the numbers, it’s worth acknowledging recent significant changes behind the scenes at Carrow Road. After 28 years at the helm it was confirmed, on 23 October, that co-owners Delia Smith and her husband, Michael Wynn Jones, would be stepping down from the club’s board with immediate effect.

Smith and Wynn Jones’ involvement in the running of the club commenced nearly three decades ago when, in December 1996, they loaned in £500,000 each; in exchange, they were appointed to the club’s board. Two years later, the couple acquired a joint holding of 42 per cent from outgoing club president Geoffrey Watling and, two months after that, their underwriting of a Rights Issue took their share of the ownership to 57 per cent, making them the club’s new majority shareholders.

That remained the case for over two and a half decades, only coming to an end in April of this year. Then, as now, Smith and Wynn Jones’ holding reduced to 40.4 per cent, a figure mirrored by Norfolk FB Holdings LLC (Norfolk), an entity that first took up a stake in Norwich in September 2022. Following a meeting of shareholders in October, it is expected that Smith and Wynn Jones’ joint stake will fall to just 10 per cent in March 2025, with Norfolk taking up the right to convert 2.5 million preference shares into ordinary ones and, in turn, assuming an 85.2 per cent stake in the club.

Norfolk is led by American businessman Mark Attanasio, who made his not inconsiderable fortune in the world of private equity. Attanasio owns the Milwaukee Brewers baseball team and has been linked with other football forays - suggestions in the summer that he was seeking a 25 per cent stake in SL Benfica have, so far, come to nought - but it is at Carrow Road that the 67-year-old has increasingly made his presence felt.

Norfolk’s purchase of a 15.9 per cent stake in 2022 came with the blessing of Smith and Wynn Jones, not least because the group was able to provide the club with much needed loan financing. April saw Norfolk and the longtime owners equalise their stakes and it’s expected that next March will see confirmation of the American group as Norwich’s new majority shareholder. It marks a seismic moment for a club that has, for so many years, been free of the ownership rumour and rancour that has plagued many a competitor.

Profit and loss account

While halving their annual deficit is good news for the Canaries, 2024 still marked the third consecutive eight-figure loss. Given Norwich were once viewed as one of the better run clubs in England - they were, for example, one of the few clubs to book profits during the Covid-19 pandemic - there’s been a clear shift in recent years. Across the last three seasons, Norwich’s pre-tax losses exceed £65 million.

Indeed, those continued recent losses are inextricably linked to the changing face of the club’s ownership. The existing owners, not just Smith and Wynn Jones but other holders of smaller stakes, simply do not have the money required to fund the losses Norwich have recently incurred. For many years the club was, in effect, self-funding; recent results clearly show that to no longer be the case.

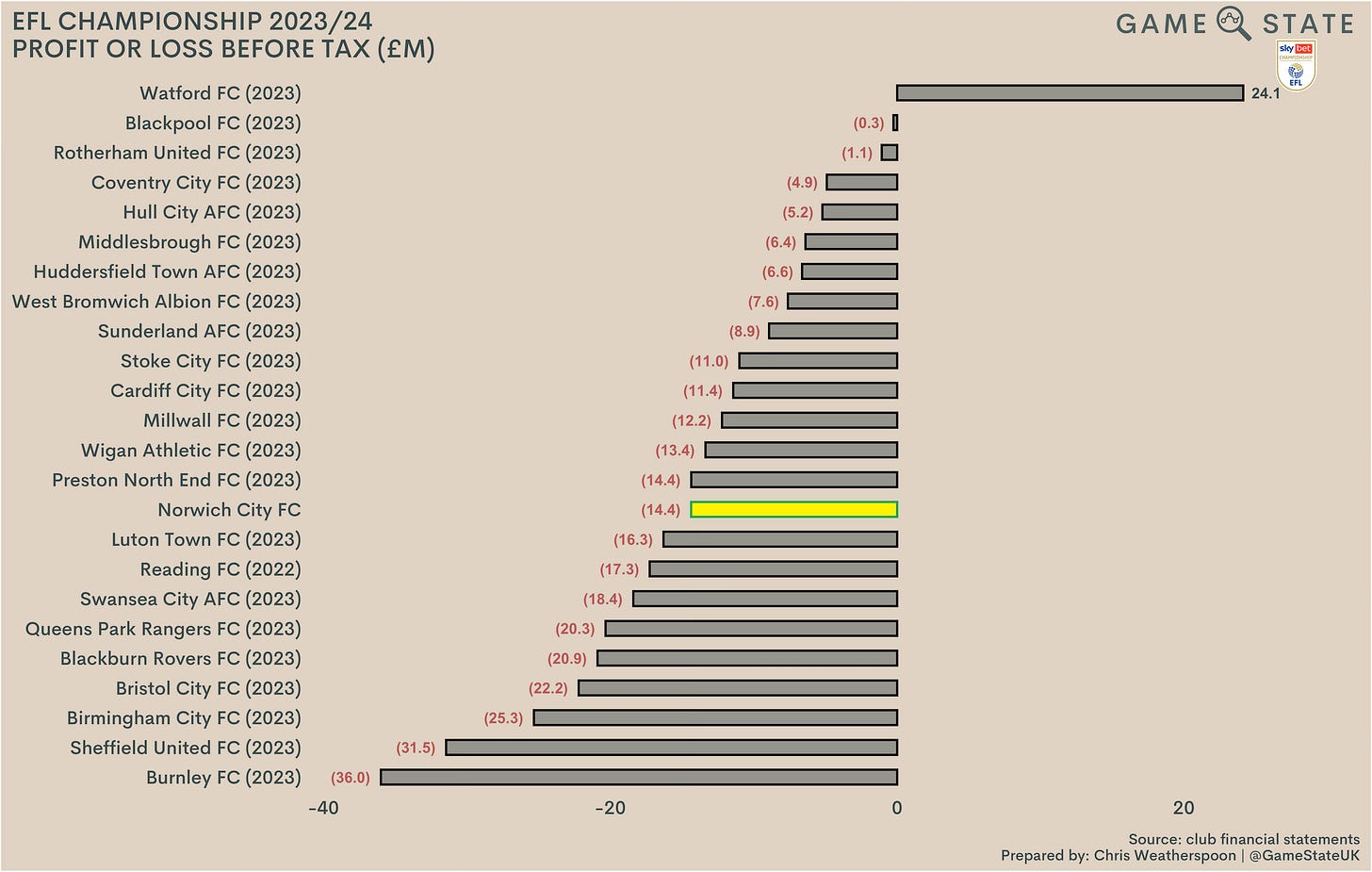

It is a mark of the poor financial health of England’s second division that Norwich’s £14 million loss is nowhere close to the Championship’s worst. Granted, they are the only club to so far published 2023/24 figures, but setting them alongside the most recent figures shows nine clubs with larger pre-tax losses. In all, using most recent figures, Championship clubs post a combined annual loss of £302 million, an average of nearly £13 million per club. And that figure would have been considerably worse were in not for Watford’s hefty player sale profits following relegation.

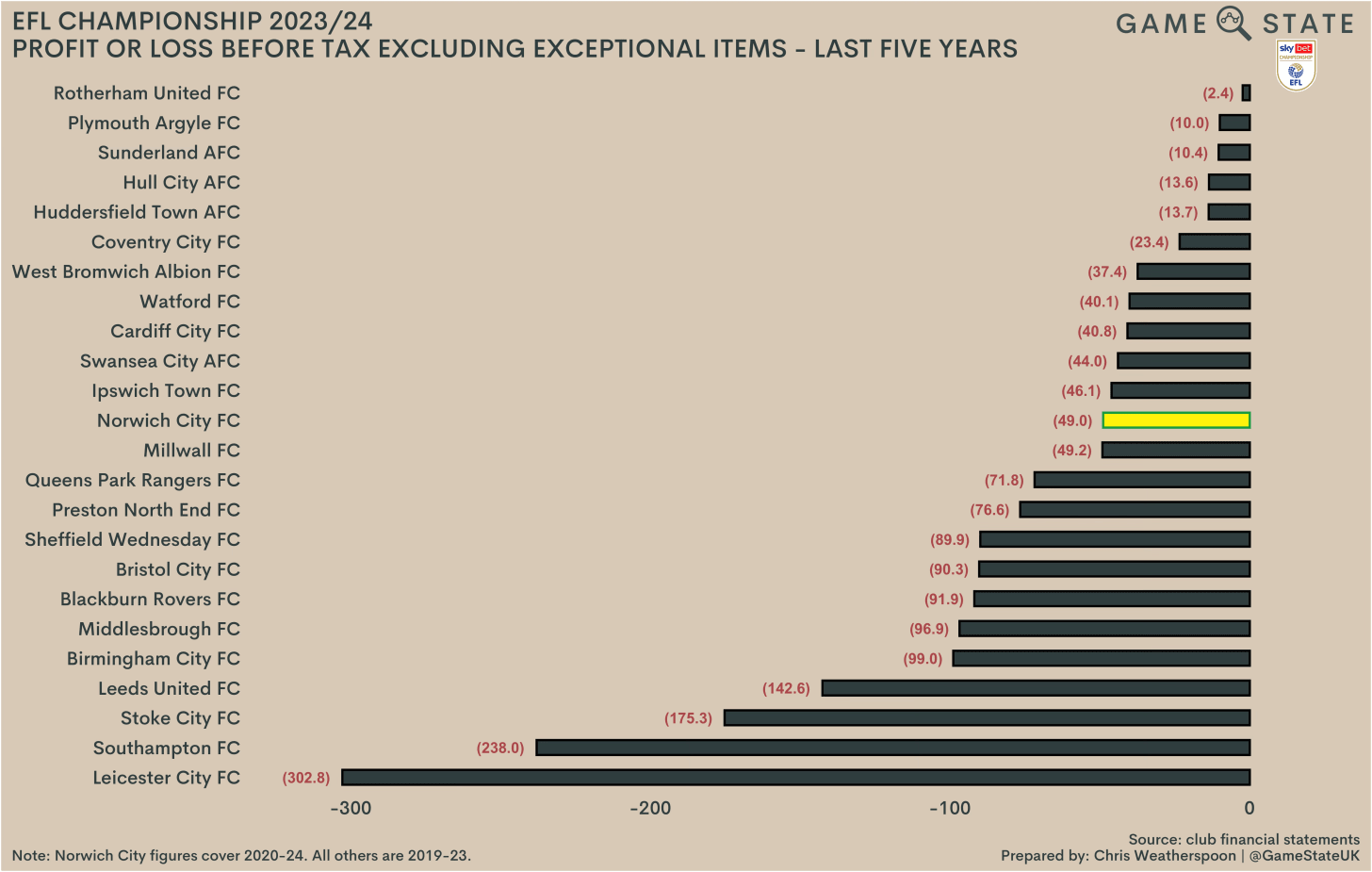

To gauge where Norwich’s recent results sit in a broader sense, it’s worth assessing the last five years of losses for last season’s Championship clubs. After stripping out one-off, exceptional items (for example, owner loan write-offs that would give a misleading picture of a club’s operational finances), Norwich’s £49 million loss over the last five years sits bang in the middle of the table, a long way behind the enormous losses incurred at the likes of Leicester City and Southampton - both of whom racked up such deficits in the EPL.

The Championship has long been a financial black hole, so Norwich’s chunky recent losses aren’t especially surprising. In pursuit of the pot of gold that awaits in the EPL, Championship clubs have long accepted sizeable losses, deducing that the riches they might eventually find make the sacrifice worth it.

A look at the last decade of pre-tax results (again after removing exceptional items) proves as much. Of the 209 pre-tax results publicly available from 2014/15 to 2023/24, just 30 clubs booked a profit. Of those, only two - Burnley in 2016 and Norwich themselves in 2021 - achieved promotion. Conversely, profitable clubs in the last decade were more likely to be relegated to League One.

Norwich are the first Championship club to post an eight-figure loss for 2023/24, but they’ll be far from the last. In total, across the last decade, Championship clubs have made a net combined loss of £2.9 billion. That’s a staggering sum, and a chief driver in the push from the EFL hierarchy for a more equitable split of the riches that now flood English football.

From an operating perspective - i.e. before player sales or one-off items - Norwich booked a £20 million loss, their ninth such deficit in the last decade. Again, that’s neither surprising nor unique in English football, as an increasing number of clubs lose money on a day-to-day basis, with the aim of offsetting those losses through effective player trading.

Even so, Norwich’s operating losses make for grim reading, with seven deficits above £20 million in the last decade. In total, between 2015 and 2024 the Canaries lost £213 million on day-to-day activities. It’s worth highlighting here that there’s a divergence between our definition of operating profit and that of Norwich’s, with the club including player sale profits in their figure, allowing them to claim they broke even at the operating level in 2023/24.

Including player sales as the club has here is contentious, not least because, as we’ll see, profits on players can fluctuate wildly from one year to the next. In any case, even using the more traditional definition, Norwich’s £20 million operating loss is nowhere close to the Championship’s worst, with 12 clubs booked a bigger operating deficit in 2023 (as did Reading, whose latest available accounts are from 2022).

Turnover

Norwich’s revenue has bounced around in line with their league status in recent years, with club record turnover of £134 million arriving in 2022, even as the club finished bottom of the EPL with just five wins to their name. 2023/24 revenue of £73 million was a 45 per cent fall on two years earlier, and a £3 million drop on the prior year, but it still represented the sixth-highest turnover figure in club history.

That reflects the continued economic might of the EPL and its attendant benefits to those clubs that compete in it, including the parachute payments that accrue to relegated clubs like Norwich. Yet Norwich’s parachute fell by around £9 million last season, so the smaller overall revenue drop means the club did find ways to offset the majority of that decrease.

What’s more, on latest available figures, Norwich’s £73 million revenue was the Championship’s highest, higher even than Burnley and Sheffield United in 2022/23, when each of those clubs received first-year (i.e. the highest) parachute payments. The Championship sees some pretty big differences in club revenues, with the parachute clubs leading the way by a sizeable margin, but Norwich’s income looks positive, particularly given they won’t receive a third-year parachute in 2024/25 and will need to rely on other sources of income as a result.

Using most recent figures, the combined revenue of clubs in the Championship was £746 million, so Norwich’s £73 million accounts for just under a tenth of that. The disparity between parachute clubs and the rest is both clear and significant. Little wonder many in the EFL want parachute payments scrapped.

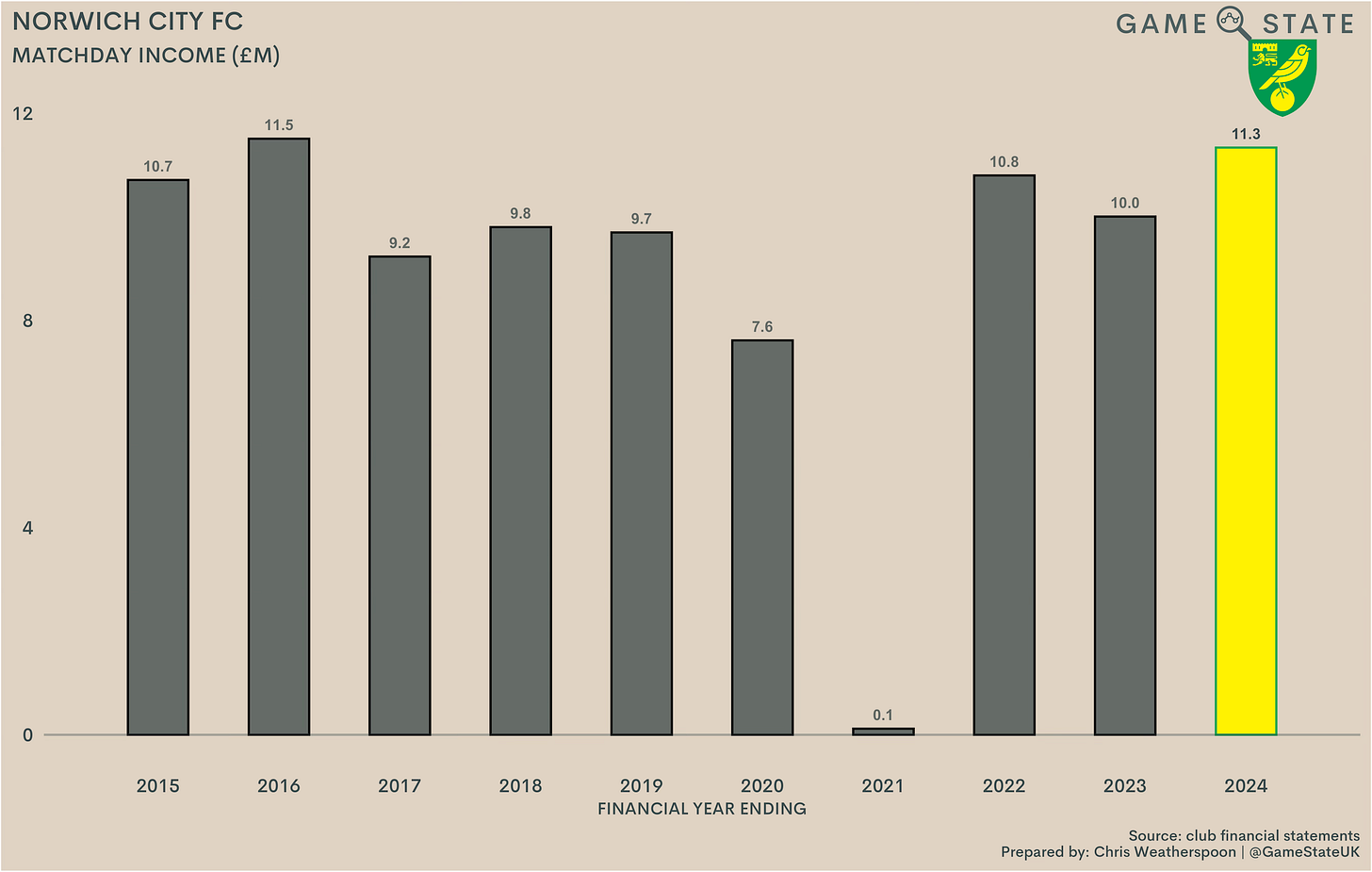

Matchday income

In terms of their differing revenue streams, Norwich have routinely been able to rely on fans filling up Carrow Road whatever division the club finds itself in. 2023/24 was no different and, if we ignore the Covid-19 years of 2020 and 2021, it was at least the eighth consecutive season where the club’s ground was at least 95 per cent full across the season.

Accordingly, Norwich booked over £11 million in matchday income for only the second time. That was a healthy 13 per cent increase on a year earlier, and only £200,000 shy of what they generated during the 2015/16 EPL season. Like all clubs, gate revenue plummeted during the Covid-19 pandemic, but Norwich’s matchday income has rebounded well since turnstiles reopened.

In fact, Norwich’s £11 million gate receipts currently stand as the most in the Championship, highlighting the usefulness of a loyal and sizeable fan base. The likelihood is Norwich will drop to at least third behind Leeds (bigger ground, historically larger matchday income) and Sunderland (bigger ground, ticket prices increased last season), but it’s still a healthy figure and quite a distance ahead of many in the second tier.

Norwich’s gate receipts are made even more impressive when we consider that they weren’t at the top for crowds last season. The Canaries’ average league attendance of 26,104 was bettered by seven clubs, so it will be interesting to see what sort of money those clubs report in gate receipts. The likelihood is Norwich will have outperformed a number of clubs that had bigger gates than them, which reflects the club’s ability to extract money from its supporters.

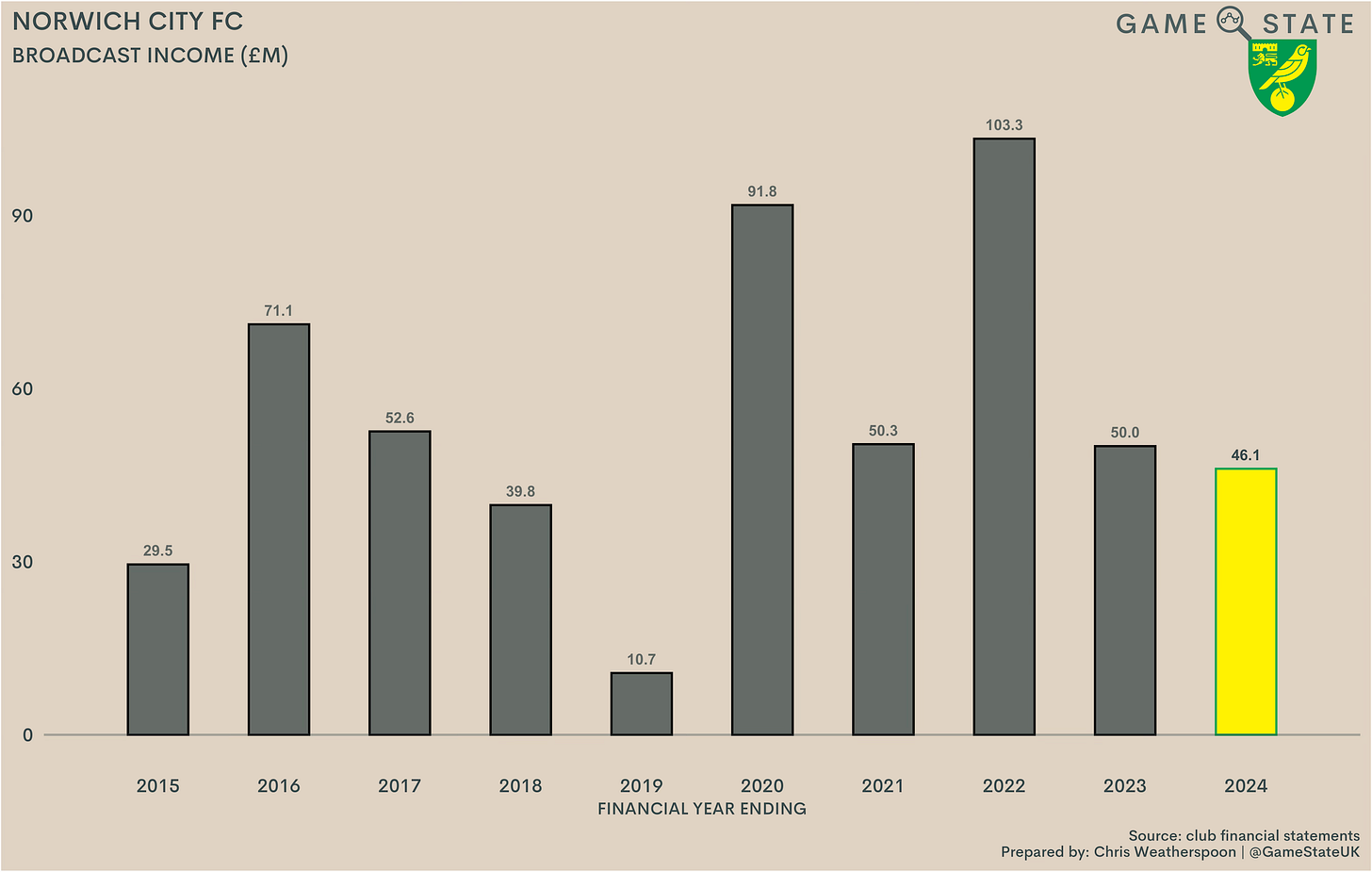

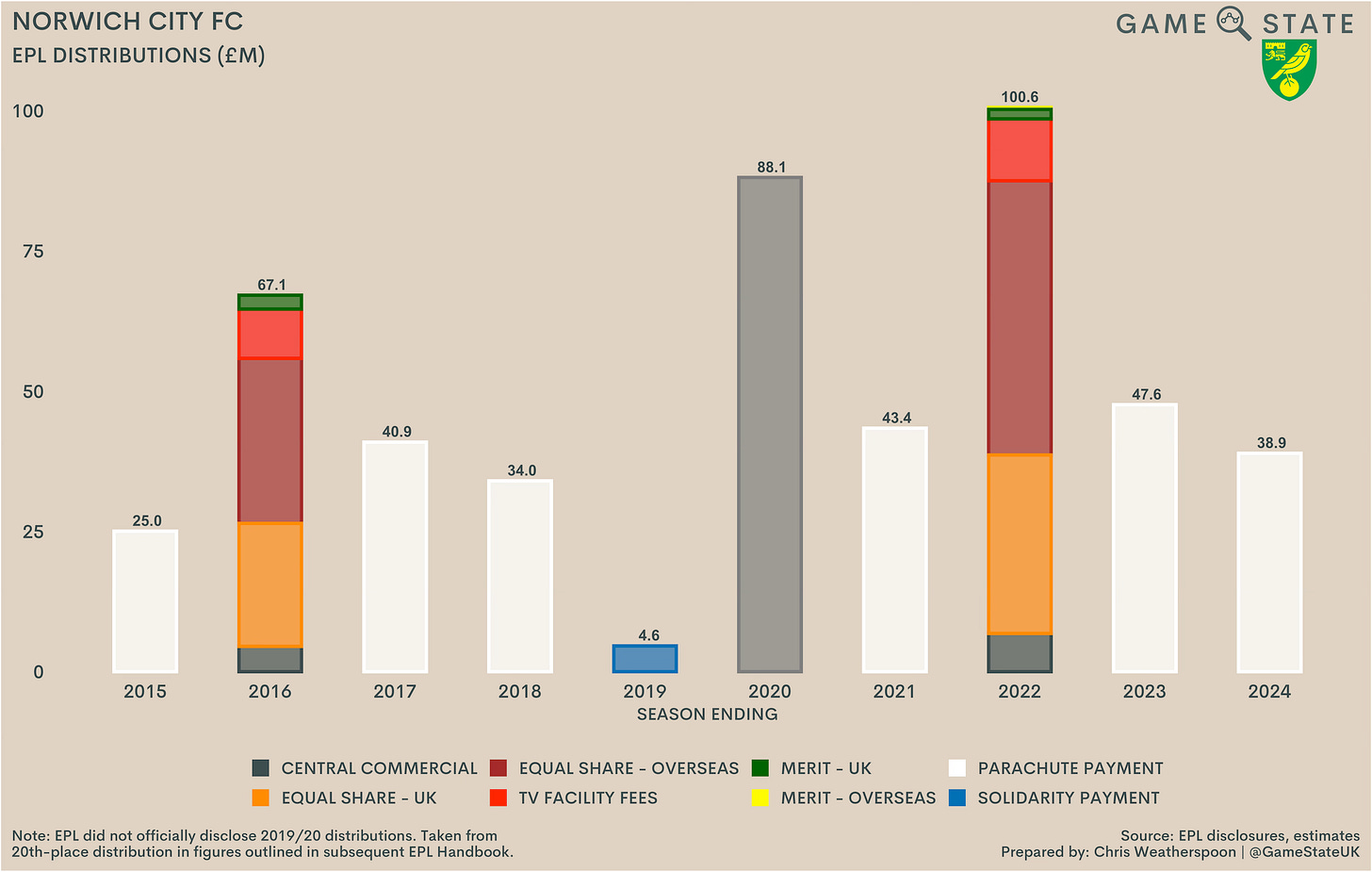

Broadcast income

Broadcast income has fallen markedly in the last two seasons, a byproduct of falling out of England’s top division. Even so, Norwich’s £46 million in TV money in 2024 was better than might otherwise have been expected. The club’s second-year parachute was estimated at £39 million, a £9 million drop from a year before, so for broadcast income as a whole to fall by just £4 million is something of an achievement.

Unsurprisingly, Norwich sit near the top of the broadcast income stakes. The disparity between recently relegated clubs and the rest is especially stark here: five clubs make in excess of £40 million, while the rest hover at a mark around a quarter of that sum. Of course, much of that parachute money has to be used on the hefty wages relegated clubs often bring down with them, but there’s still a clear gulf in resources in the Championship at present.

Despite spending only three of the last 10 seasons in the EPL, Norwich have received less than £25 million in Premier League distributions just once in the last decade. In that time, the Canaries have received £490 million in TV money from England’s top division, with £230 million (47 per cent) of that arriving in the form of post-relegation parachute payments.

Owing to their failure to survive beyond one season in their most recent stint in the EPL, Norwich, once again, don’t qualify for a third-year parachute payment in the current 2024/25 season. As a result, their EPL distribution will be limited to the solidarity payment that is given to all Championship clubs other than those receiving parachutes. Last season, the solidarity payment stood at £5.2 million, and it’ll be much the same this year too.

Norwich will also benefit from the EFL’s new TV deal which came into force at the beginning of the current season. Estimates suggest Championship clubs will only see an extra £2 million or so per season from the new deal, which is hardly much to write home about, but in Norwich’s case they’ll be glad of any uplift they can find now that their parachute payments have run out.

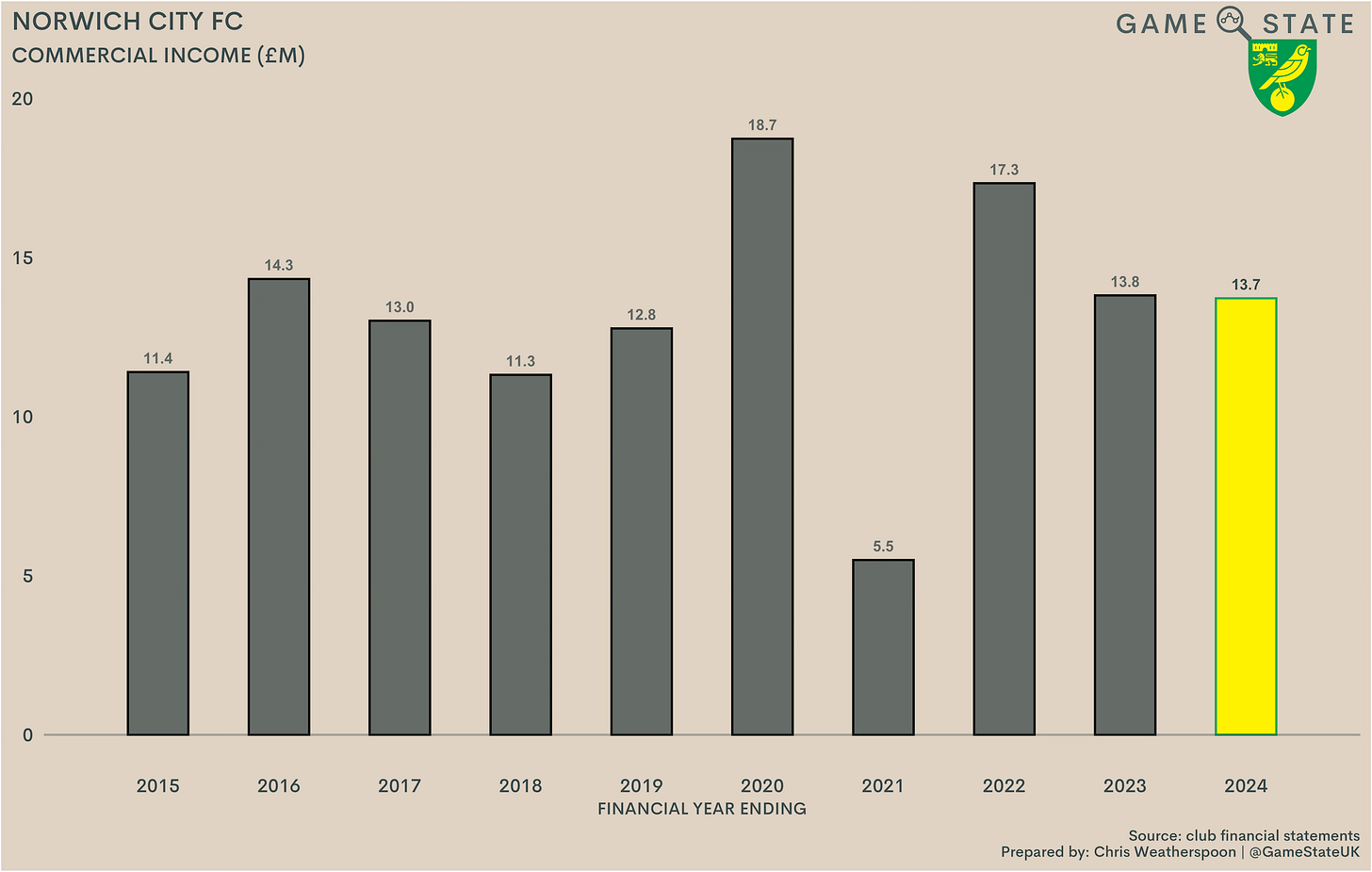

Commercial income

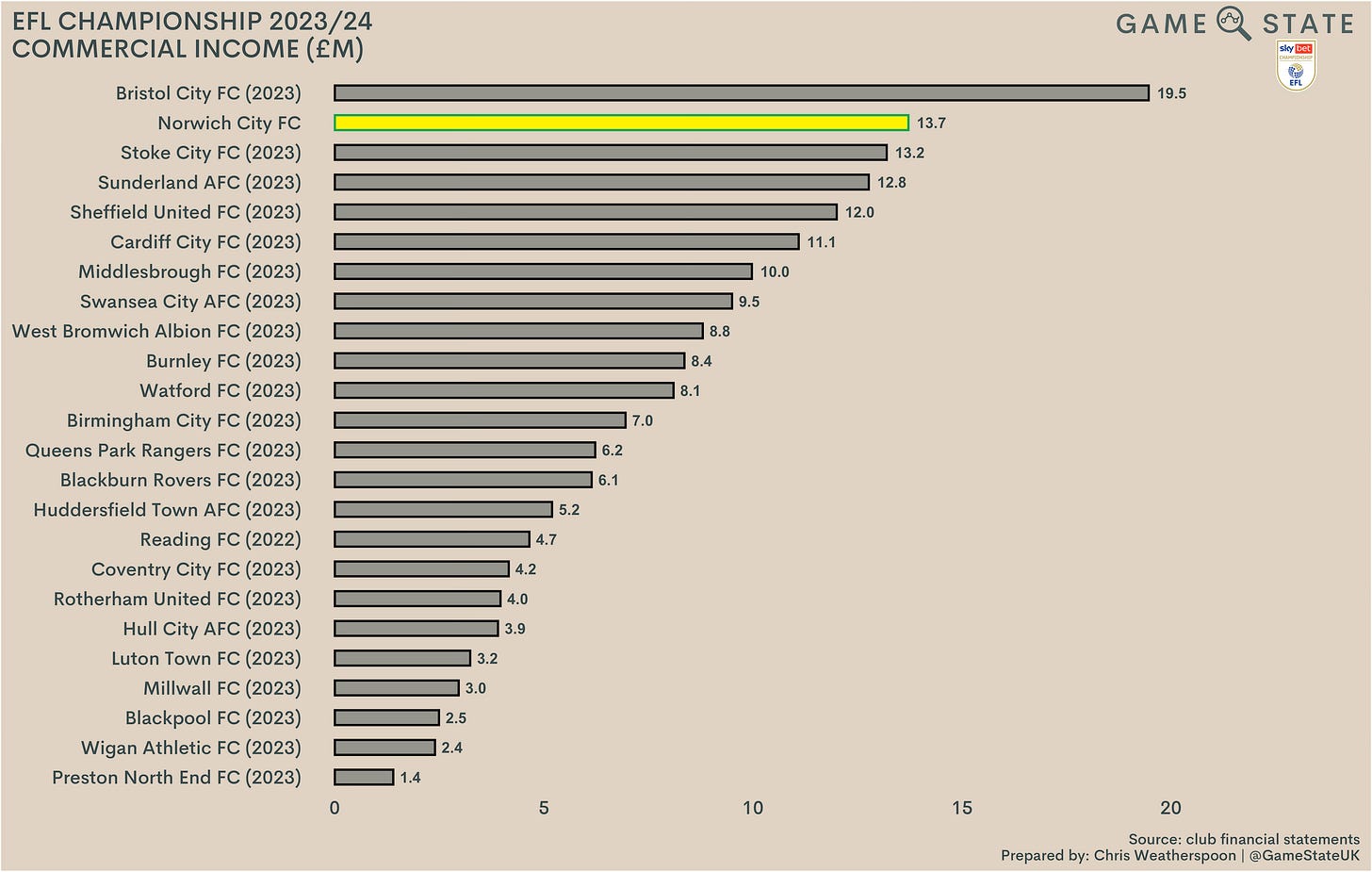

Throughout football, clubs are increasingly looking to boost commercial incomes, and Norwich appear on face value to have room for growth there too. £14 million of commercial revenue in 2024 was a very slight dip on a year earlier, as small increases in sponsorship and catering were offside by a near-half million pound fall in the club’s retail income.

Norwich’s high watermark for commercial income came in the truncated 2019/20 season, so it’s difficult not to wonder whether the pandemic arrived at the worst possible time for the Canaries in this regard. That being said, they did rebound to over £17 million in their last season in the EPL and, unlike the club’s attendances, Norwich’s divisional status does impact how much the club can generate commercially. In particular, sponsorship revenues are higher when Norwich are in the top tier.

Norwich’s £14 million commercial income is actually the second-best in the Championship currently, albeit a long way behind Bristol City’s impressive £20 million. The Canaries commercial offering is clearly decent, though it looks like they’ll struggle to realise too much more of it any time soon without achieving promotion.

Wages

On the expenditure side of the ledger, Norwich’s wage bill reduced by around £5 million, an eight per cent drop on 2023. From the club record of £118 million two years ago, a sum that still proved insufficient in achieving EPL survival, Norwich’s staff costs have more than halved, an essential exercise given the concurrent decline in revenue.

Norwich are the only Championship club to publish 2023/24 accounts, so it’s hard to compare with the wage bills of others. But it’s fairly clear that £52 million in staff costs puts them at the top end of the division. Indeed, Norwich’s wage bill was more than Sheffield United’s was in 2022/23, when The Blades were promoted, and only Burnley’s wage bill is currently higher.

That may well change once Leicester City, Southampton and Leeds United publish their accounts for last season, but it’s possible that finishing sixth still represented an underachievement for Norwich in 2024.

Having said that, it was a definite improvement on 2022/23. Then, Norwich’s £56 million wage bill garnered just 62 points - the median points tally in the second tier across the last decade. During the last 10 years Norwich have routinely spent a fair bit more than the average Championship side on wages, and in 2022/23 they spent more than anyone else, even while finishing 13th.

In their most recent promotion seasons, the Canaries out-performed their wage bill, finishing as second tier champions in 2019 with the third-highest staff costs and winning the league again two years later with the second-highest.

2023’s underperformance is made all the more disappointing when we consider that clubs with lower wage bills will have included promotion bonuses within those, so Norwich’s underlying staff costs really didn’t produce value for money. The Canaries did sack manager David Wagner in May, the costs of which are included in their wage bill, alongside any costs to remove his assistant, Christoph Bühler. However Wagner was employed on a 12-month rolling contract, so Norwich didn’t have to pay off multiple years of wages to their outgoing head coach.

The extent, if any, of 2024’s underperformance remains to be seen, but Norwich’s wage bill last season was the ninth time a Championship club has spent more than £50 million on wages while failing to be promoted, and the Canaries have the ignominy of appearing within that list of nine on four separate occasions.

The expectation is that once Leeds United publish last season’s accounts the number will grow to 10, which reflects how wages have continue to go up and up in football, but it’s still a lot of money to spend when promotion ultimately doesn’t arrive. It will be interesting to see how much East Anglian rivals Ipswich Town spent in their own successful bid for Premier League status.

While Norwich’s wages were high for the division, so was their income. The club’s small decline in revenue was outpaced by the cuts to the wage bill, leading to a fall in their wages to turnover metric, dropping from 75 to 71 per cent.

That’s a healthy figure, especially in England’s second tier. In fact, it’s the second-best in the Championship, only bettered by the 66 per cent on display at since-relegated Rotherham United. Half of the Championship booked wages in excess of revenue in 2022/23, so Norwich’s 71 per cent stands up particularly well against divisional peers.

Having said that, the club will still need to get wages down yet further in 2024/25. The sales of Gabriel Sara and Adam Idah this summer will have helped, though even with their departures Norwich’s wages to revenue ratio will almost certainly rise this year, as the fall in money from the EPL - from a £39 million parachute to £5 million in solidarity monies - will surpass any wage cuts, and it’s unlikely revenue gains elsewhere will offset the difference.

Other expenses

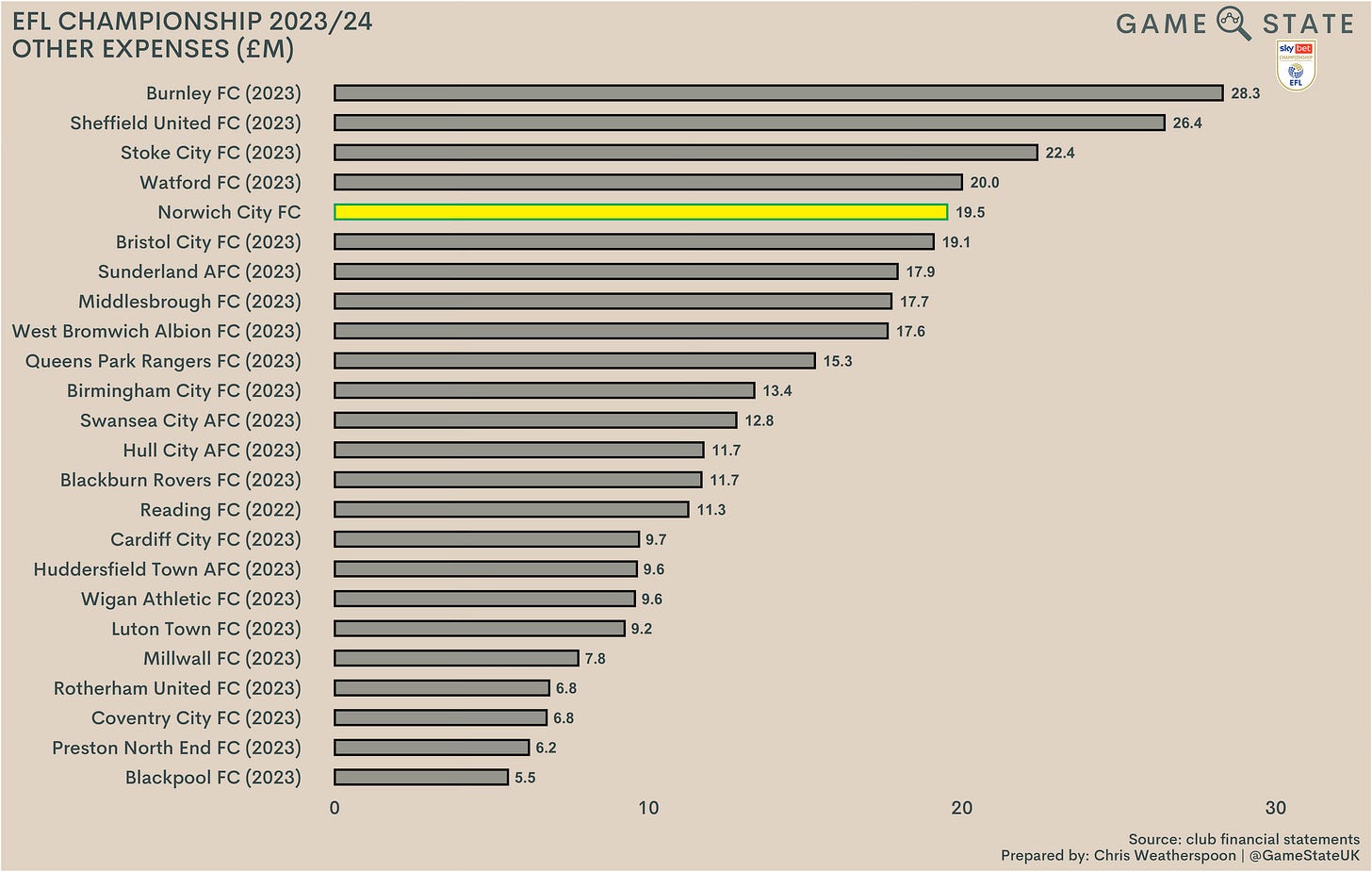

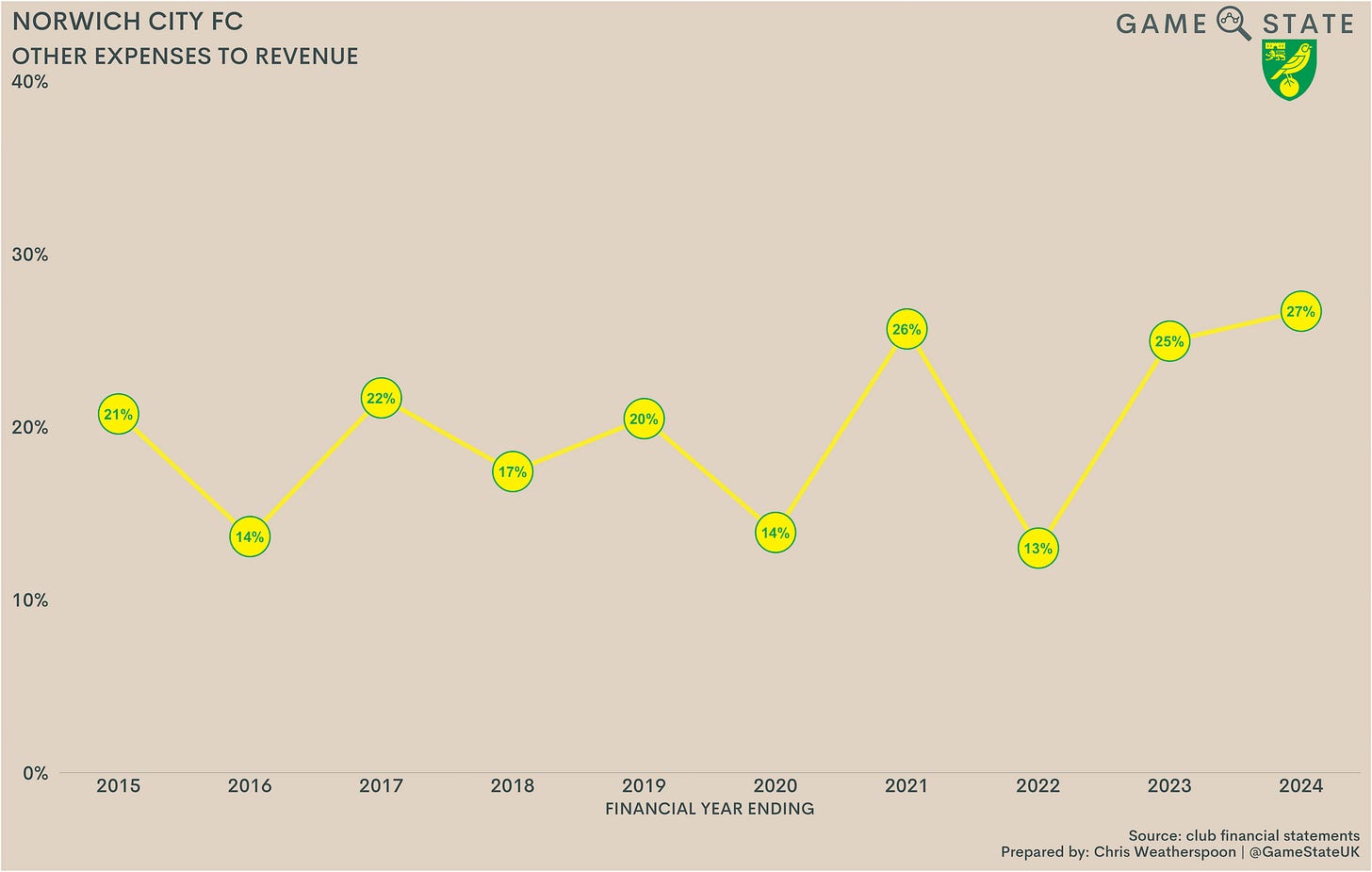

In terms of non-staff costs, Norwich’s other expenses hit a club record £20 million, driven in part by inflation. English clubs are often fairly coy on what these expenses entail, so there’s not much detail here, but Norwich’s three per cent increase on 2023 is indicative of nothing too drastic changing behind the scenes last season.

Even so, that figure was the fifth-highest in the Championship, generally only topped by recently relegated clubs. Carrow Road is one of the bigger grounds in the second tier, and in an affluent area too, so higher costs aren’t especially surprising for Norwich, but it’s worth highlighting that ‘other expenses’ often relate to fixed costs that need to be paid regardless of other circumstances. It’s in clubs’ interests to keep such costs at a level that doesn’t adversely impact the ability to improve their playing squads.

To that end, it’s worth looking at how much of Norwich’s income was gobbled up by non-staff expenditure. Last year actually represented a 10-year high in this regard for the club, with other expenses accounting for 27 per cent of revenue. That’s unsurprising given the reduction in parachute payments; on the contrary, the three lowest figures in the below graphic all appear in EPL years.

Despite that, 27 per cent is a healthy figure for a Championship club. In fact, based on most recent accounts, Norwich’s other expenses to revenue figure is the lowest in the division, and they’re one of only five clubs who spend less than a third of income on such costs. Compare that with the hefty burdens seen at Stoke City, Birmingham City and Reading.

Of course, this was a year in which Norwich enjoyed the benefit of parachute payments. Had those been removed and replaced with the £5 million solidarity payment the club will receive this season, this particular metric would have leapt to 57 per cent, and ninth-highest in the division. Naturally, that would widen losses, a fact of life for most Championship clubs.

Player trading

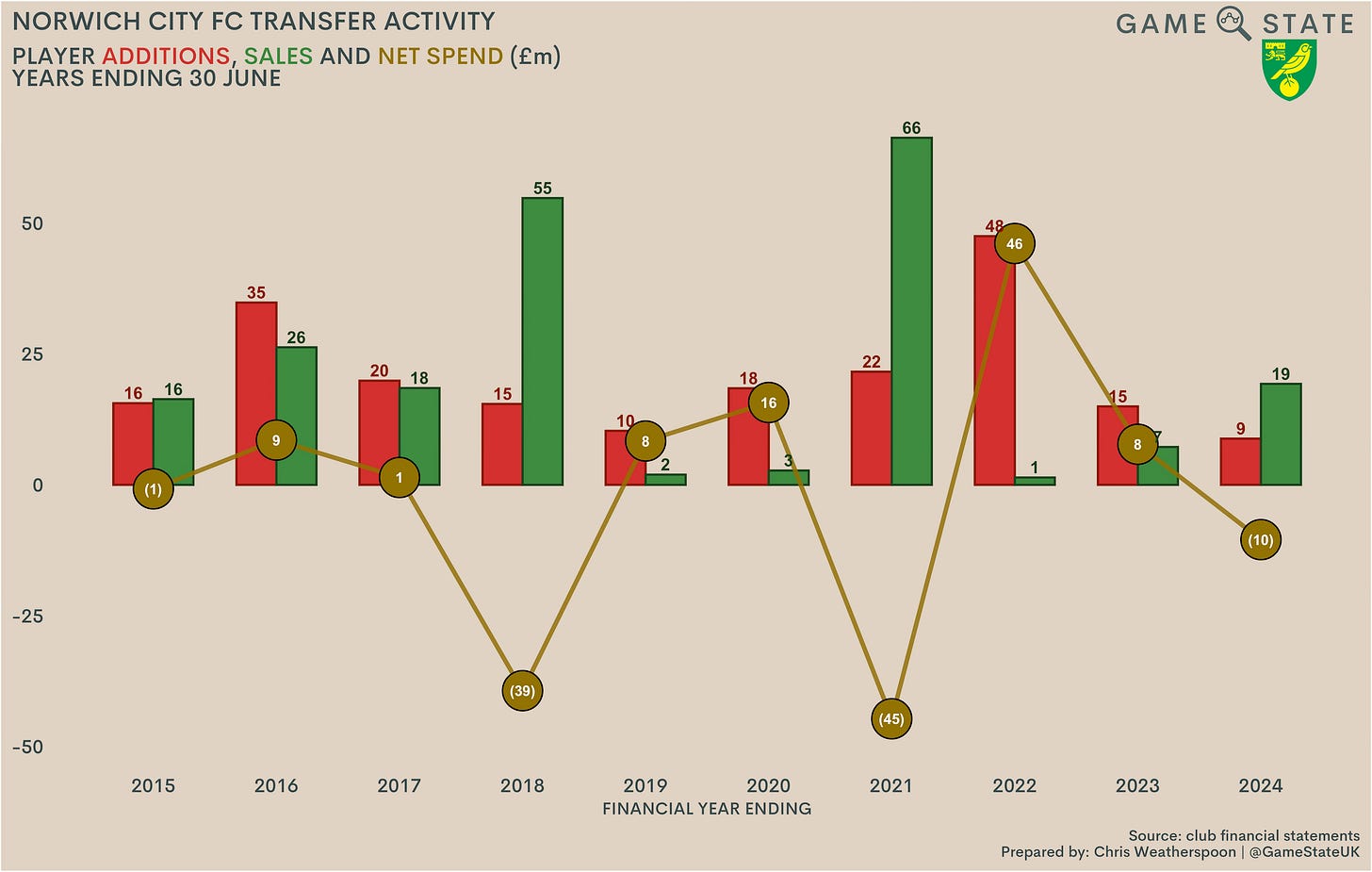

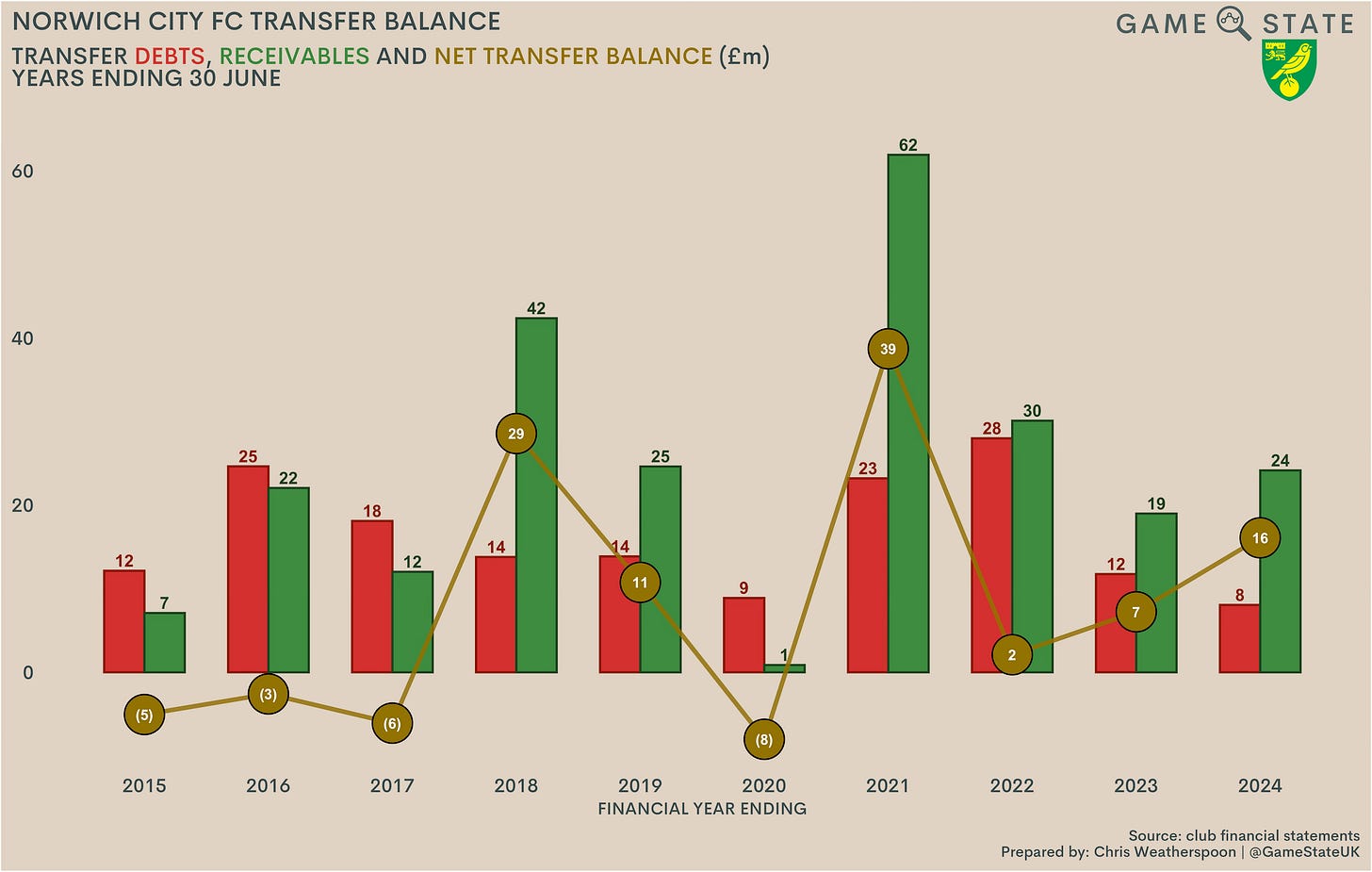

After two years of net positive spending on transfers, Norwich booked more in sales (£19 million) than they spent (£9 million) in 2023/24. That’s not too surprising given the club’s extended departure from the EPL; an attempt at a quick return in 2023 failed miserably, so some belt tightening was always likely.

In an effort to lower losses, quite a few Championship clubs now spend less than they take in on transfers, so Norwich were far from alone in this regard. In 2023, 14 clubs have a negative net transfer spend, and of the other 10 only two - Burnley and Blackburn - spent more than 20 per cent of turnover on transfers. In Burnley’s case, their accounting date of 31 July skews things, as much of their 2022/23 spend came after promotion back to the EPL,

Norwich’s negative net spend last season is even more pronounced when we dig into the deals that took place. Of their £9 million spend on incomings, a third went on defender José Córdoba, who signed in the summer of 2024 but fell into last season’s accounting period. Stripping him out leaves net transfer income of £13 million in 2023/24, as opposed to a net spend of £8 million a year earlier, which is a neat little example of how club transfer spends rarely prove a strong indicator of future success or failure.

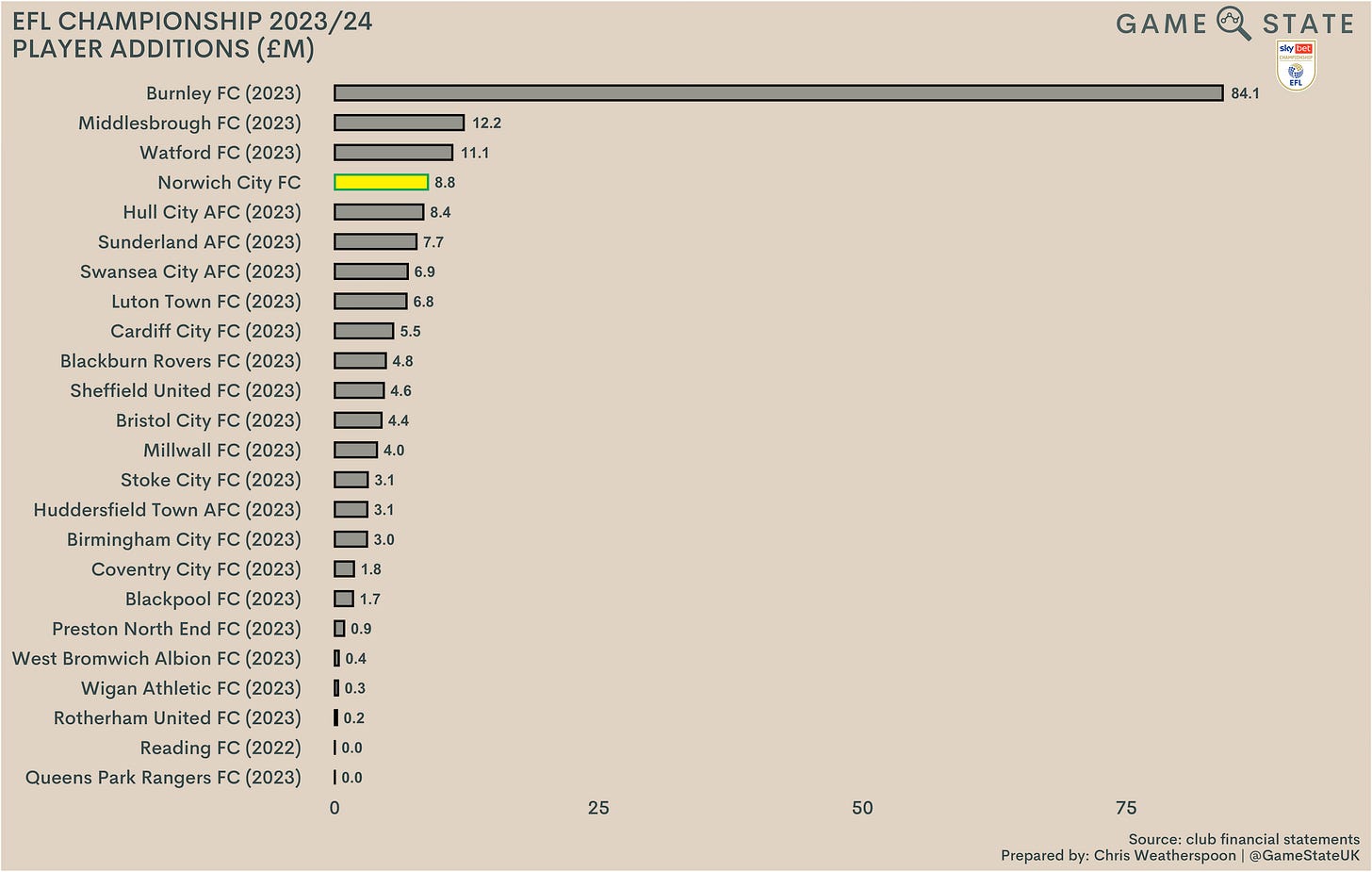

Norwich’s £9 million spend on new players was the fourth-highest among recent Championship results, though again Burnley’s £84 million spend is skewed by the timing of their accounting period. A majority of Championship clubs spent less than £5 million in their most recent accounts, a reflection of the cost pressures that clubs in England’s second tier face and the impact it has on their ability to spend heavily on transfers.

On the selling side, Norwich booked £19 million in sales, principally from the departures of Andrew Omobamidele to Nottingham Forest and Max Aarons to Bournemouth. That’s a common theme for relegated clubs, whereby those players who have proven themselves able to perform in the EPL are snapped up by sides from the league they’ve just left.

Nowhere was that more evident in 2023 than at Watford, who booked a whopping £76 million in player sales, with a little under half that coming from João Pedro’s move to Brighton and Hove Albion. No one else came close to that total, but Norwich’s £19 million was the fourth most in the Championship on recent figures.

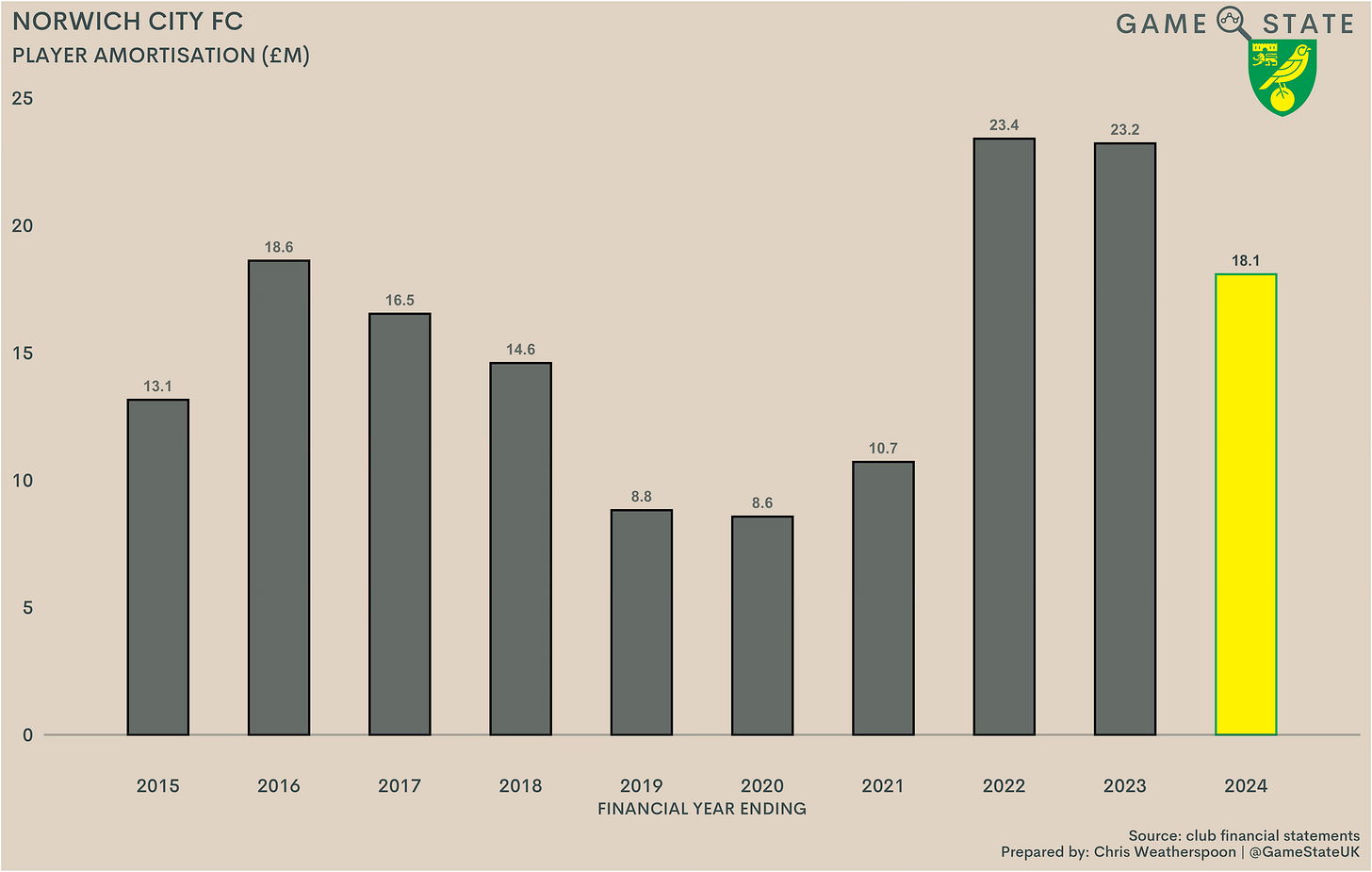

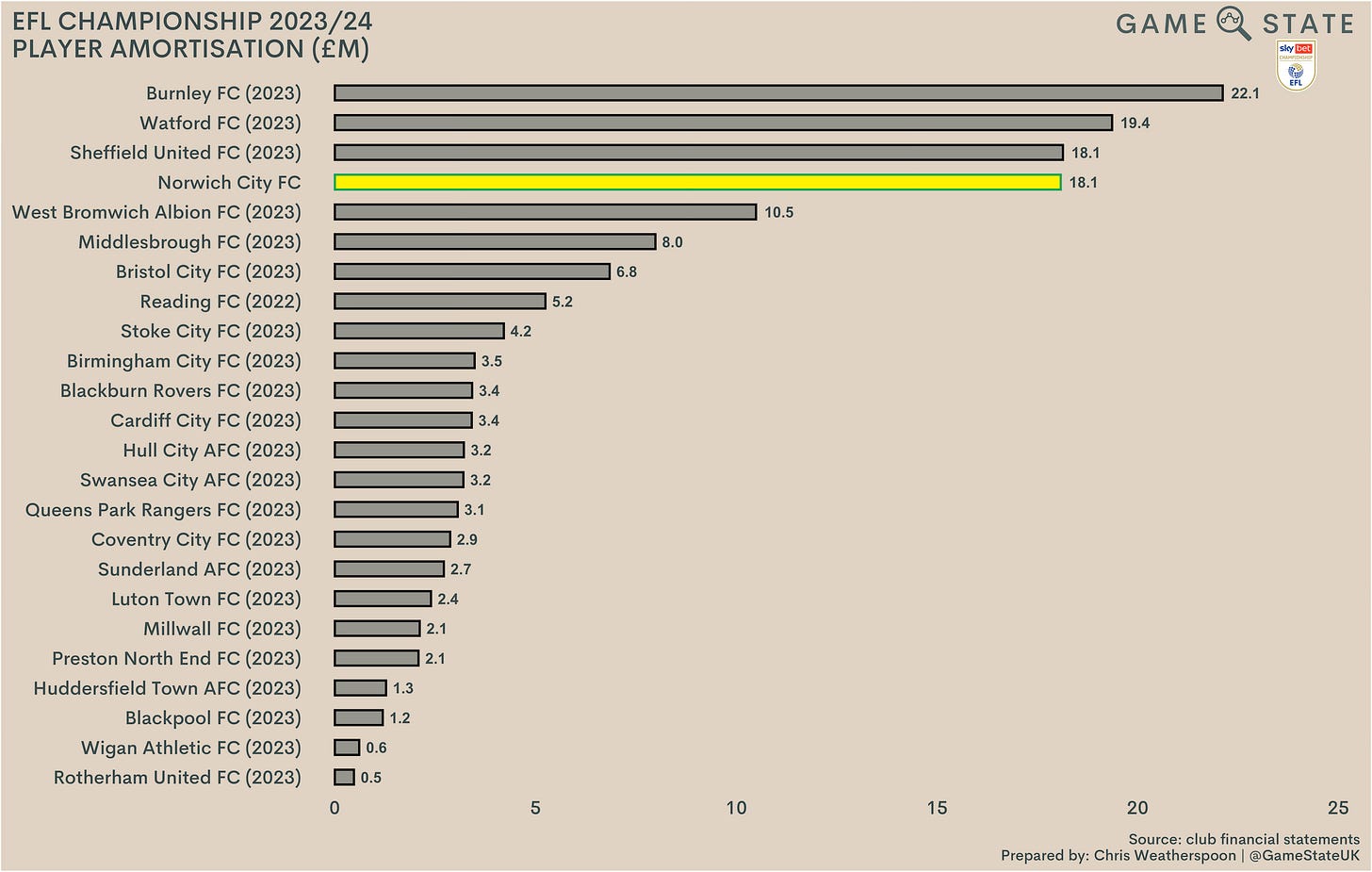

The upshot of that activity was a £5 million reduction in the player amortisation (effectively, the cost of a transfer spread across a player’s contract term) hitting Norwich’s income statement in 2024. This was a drop of around a fifth from the club record levels seen in 2022 and 2023, though is still historically high for the Canaries.

It’s high for the Championship too, again ranking Norwich fourth. That’s again unsurprising; the club spent heavily (by their standards) to try and retain EPL status in 2022. When that didn’t happen, several players signed for big fees remained at Carrow Road, including the likes of Angus Gunn, Christos Tzolis and Ben Gibson. As a result, their amortisation remained high.

That should improve in 2024/25, as a number of those signed for big fees have now left the club, including Gibson (estimated annual amortisation charge of £3 million), Tzolis (£2 million) and Sara (£1.5 million). Having said that, those gains will be offset by the costs incurred on new signings made in the summer of 2024.

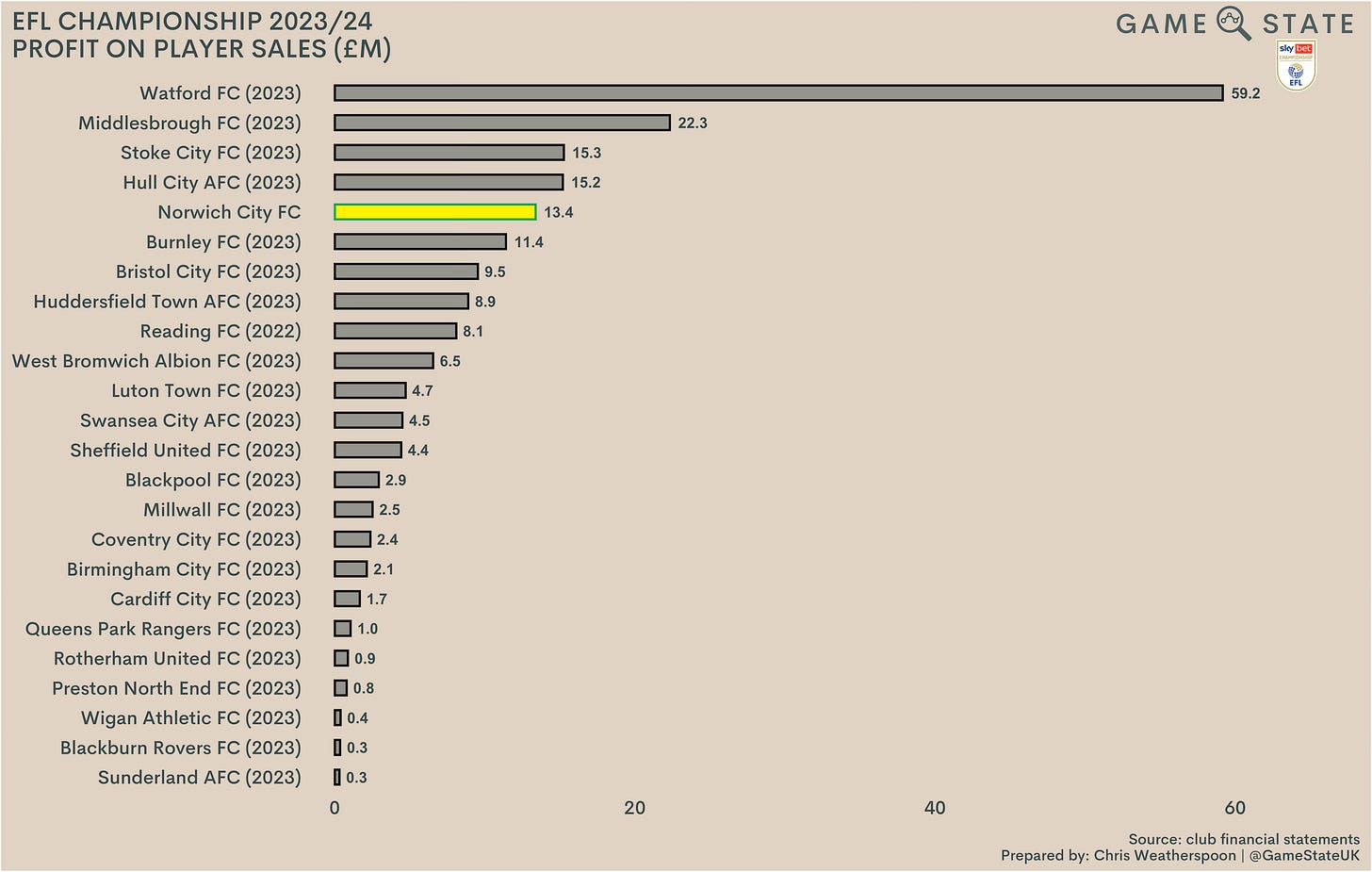

Norwich booked £13 million in player profits in 2024, principally on the sale Omobamidele to Forest whose £11 million fee, as a graduate of the club’s academy system, was almost entirely booked as profit.

Norwich haven’t been especially consistent sellers, though did book over £100 million profit across 2018 and 2021 combined, as the sales of James Maddison, Emiliano Buendía, Ben Godfrey and Jamal Lewis provided a necessary boost to club finances. Across the last decade, they’ve sold players for a combined £215 million, recognising £175 million of that as profit.

Unlike some fellow relegated clubs, Norwich haven’t seen particularly big player sale profits following their most recent demotion, and their result here will look poorer once the remainder of the division publishes accounts, as the relegated sides enjoyed soft hefty sales in 2023/24. Where in 2021 Norwich benefited from the sales of Buendía, Godfrey and Lewis, the last two years have seen the club struggle to recoup anywhere near as much for key players. Even so, the sale of Omobamidele on its own turned a higher profit than 18 Championship clubs managed overall in their most recent figures.

Taking transfer activity in single-season isolation isn’t all that useful, as clubs’ activity in the market tends to wax and wane in a given year dependent on the current status of their squad. Sir Alex Ferguson once remarked that it takes three years to (re)build a football team, so that seems as good a range as any to assess player profits over.

Doing so ranks Norwich pretty low in the Championship, with just £17 million in player profits from 2022 to 2024. As is now a theme, the relegated clubs dominate the top end of the rankings here, which would be fine if Norwich weren’t a recently relegated club themselves.

In truth, the Canaries’ recent transfer activity leaves plenty to be desired, and the fact the bulk of their profit came from an academy graduate doesn’t exactly show it in a better light. Perhaps the best (or worst) example of the club’s recent transfer follies comes via now departed winger Tzolis. Having signed for the club in 2021 for around £10 million, he left in summer 2024 for just £3 million, with Fortuna Düsseldorf exercising a buy option after a separate loan. Almost immediately, Fortuna booked £2 million profit on Tzolis, selling him to Club Brugge for around £5 million.

Squad cost

Norwich’s playing squad at the end of June was the third most costly in club history at £76 million, reflecting the high relative spend on players. That comes even after the club booked a shade under £2 million on impairing player values (in effect, accepting that they won’t recoup the book value of a player, and taking the cost now rather than a loss on sale).

Still, such are the costs of trying to compete in the EPL that Norwich’s squad cost remains one of the highest in the second tier. Again, Burnley’s number here is skewed by the timing of their accounting date, but it’s no surprise that the costliest squads are present at those clubs who’ve recently been relegated. At the bottom end, it is clear to see why the likes of Rotherham United and Wigan Athletic have struggled following League One promotion.

Balance sheet

Football debt

For the sixth time in the last seven years, Norwich’s transfer balance - amounts the club is owed for sold players less amounts owed to other clubs on purchased players - was positive, sitting £16 million in the black. That’s the natural product of the transfer activity we’ve already discussed, but it’s still a good thing, as it means there shouldn’t be any risk of Norwich failing to make transfer payments as they fall due.

Where in the EPL clubs often hold big negative transfer balances, that isn’t really the case in the Championship. Most clubs don’t sway too far one way or the other, so Norwich, along with Watford (big transfer fees owed to them) and Burnley (big transfer fees owed to others) represent outliers in this sense.

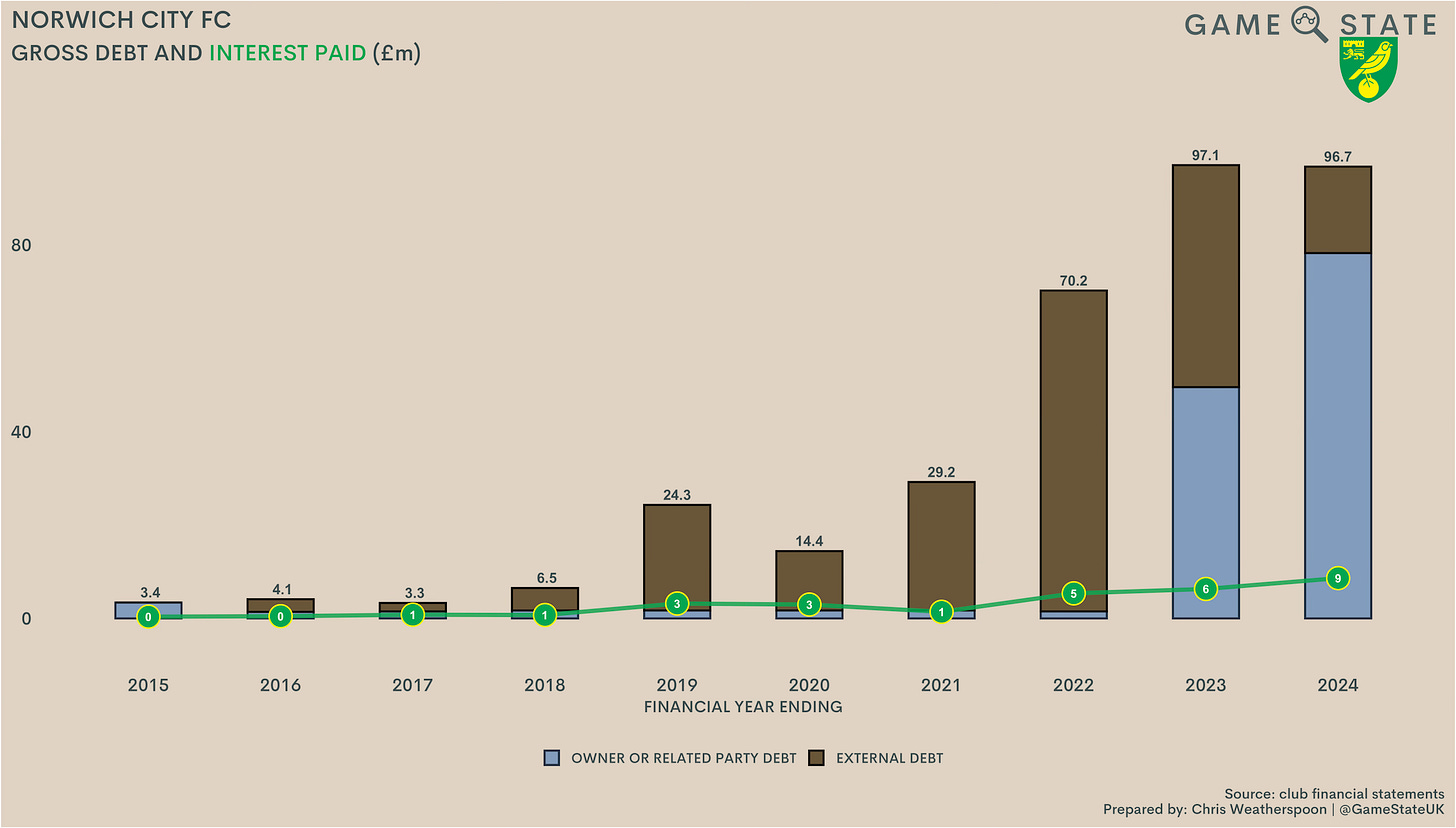

Financial debt

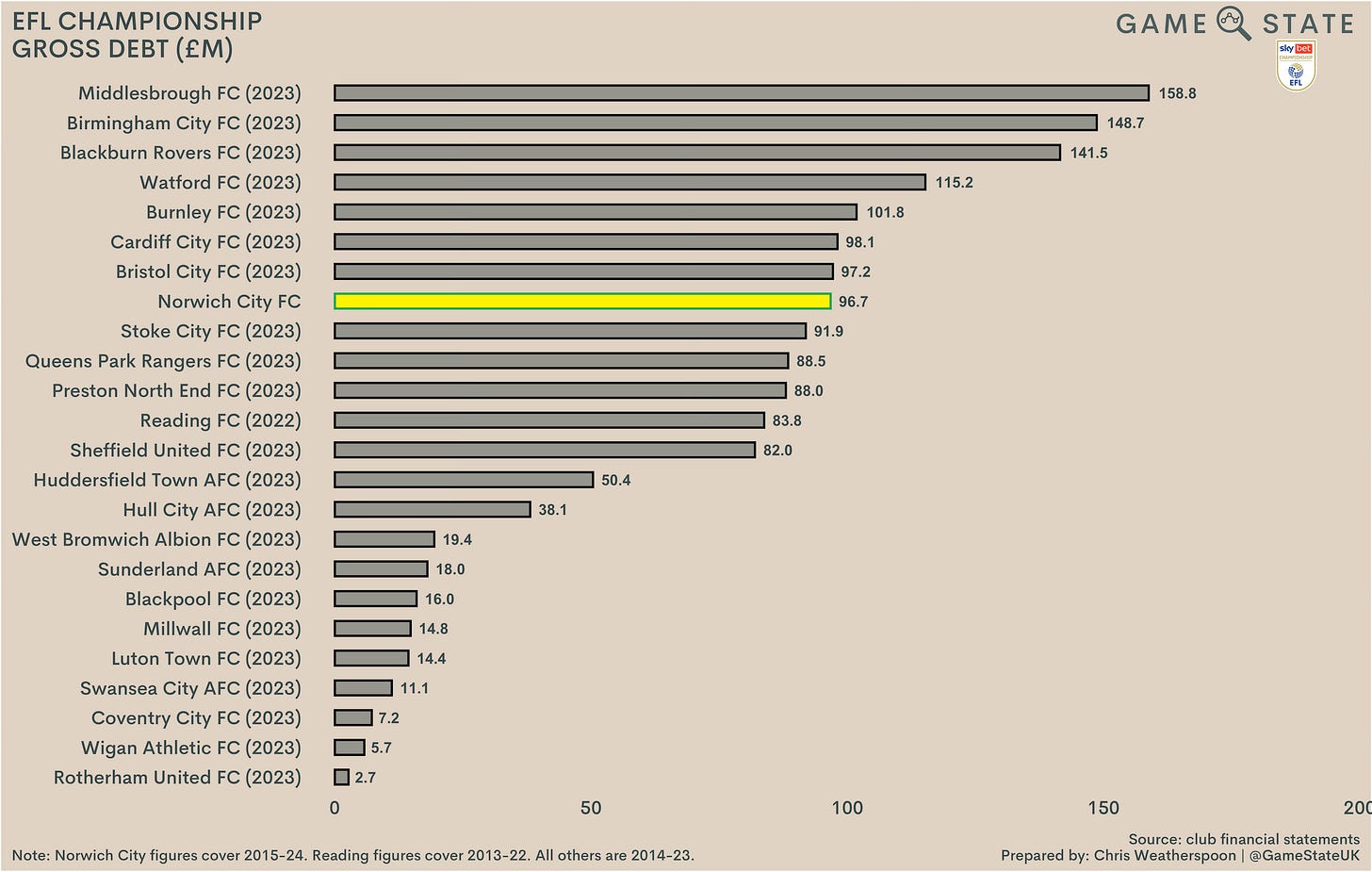

On the contrary, Norwich’s financial debt has ballooned in recent years, thought it has levelled off at around £97 million in the last two seasons. As recently as 2018 that figure was below £10 million, with the increase reflecting the difficulties the club has faced as a result of both the Covid-19 pandemic and ineffectual transfer dealings (and the accompanying bump in the wage bill).

While the Canaries’ gross debt figure was largely unchanged, the make-up of the outstanding loans shifted. Norwich’s external debt fell by £29 million, as it was paid down with funds from the owners, principally Mark Attanasio through the Norfolk Holdings entity. At the end of June, Norwich’s debt was split £78 million to owners and £19 million to external lenders, with a chunk of the latter comprising factored debts on player receivables, whereby Norwich receive transfer fee instalments early in exchange for the factoring entity taking a cut.

Bringing debt in house is generally a good thing, and Attanasio’s arrival has undoubtedly been needed to support the club financially, but the shifting ownership picture has brought with it a noticeable increase in interest costs. From basically nothing seven years ago, Norwich’s interest paid hit £9 million (£8 million net) in 2024, thought it’s worth highlighting here that the interest amounts in the club’s cash flow statement exactly mirror those in the income statement, which isn’t usually the case. Whether that’s an error is unknown, and we have to take the accounts at their word, but it does seem peculiar, and it may be the case that Norwich’s owner loans are accruing interest but the club aren’t actually having to pay it, as is common practice at Championship clubs nowadays.

Based on most recent figures, Norwich had the Championship’s eighth-highest debt, slotting into a slew of clubs with debts in the £80-100 million range. Much of this debt is internal, so costs little for clubs to service, but Norwich are still conforming to the unwritten rule of the Championship: the longer you stay there, the bigger your debts will be.

Returning to that interest paid, if the cash flow statement is correct, Norwich’s £9 million paid in 2024 was by some distance the most in the Championship. Even if that figure is high compared to reality, Norwich still won’t fall into the group of clubs who incur no finance costs, as those factored player sales come with a fee.

Taking the net interest paid figure of £8 million in 2024 accounts for over 10 per cent of Norwich’s income, a chunky slice given they were in receipt of parachute payments last season. Assuming it is accurate, that’s the highest proportion of turnover the club has spent on financing costs in the last decade - and probably ever.

On a proportion of revenue basis, only Cardiff City paid out more in interest in the Championship, highlighting the impact such costs can have on a team’s competitiveness. Things will only get worse in the short-term on this front too, as Norwich’s income declines this season. The debts owed to Attanasio have recently been converted to preference shares accruing dividends at 11 per cent; a rough estimate suggests Norwich’s interest to turnover ratio will rise to 15 per cent in 2024/25. Of course, that’s dependent on whether Attanasio actually accepts payment of those preference dividends, and the uncertainty we’ve highlighted around the 2024 cash flow statement makes this a fairly hazy topic to get to the root of.

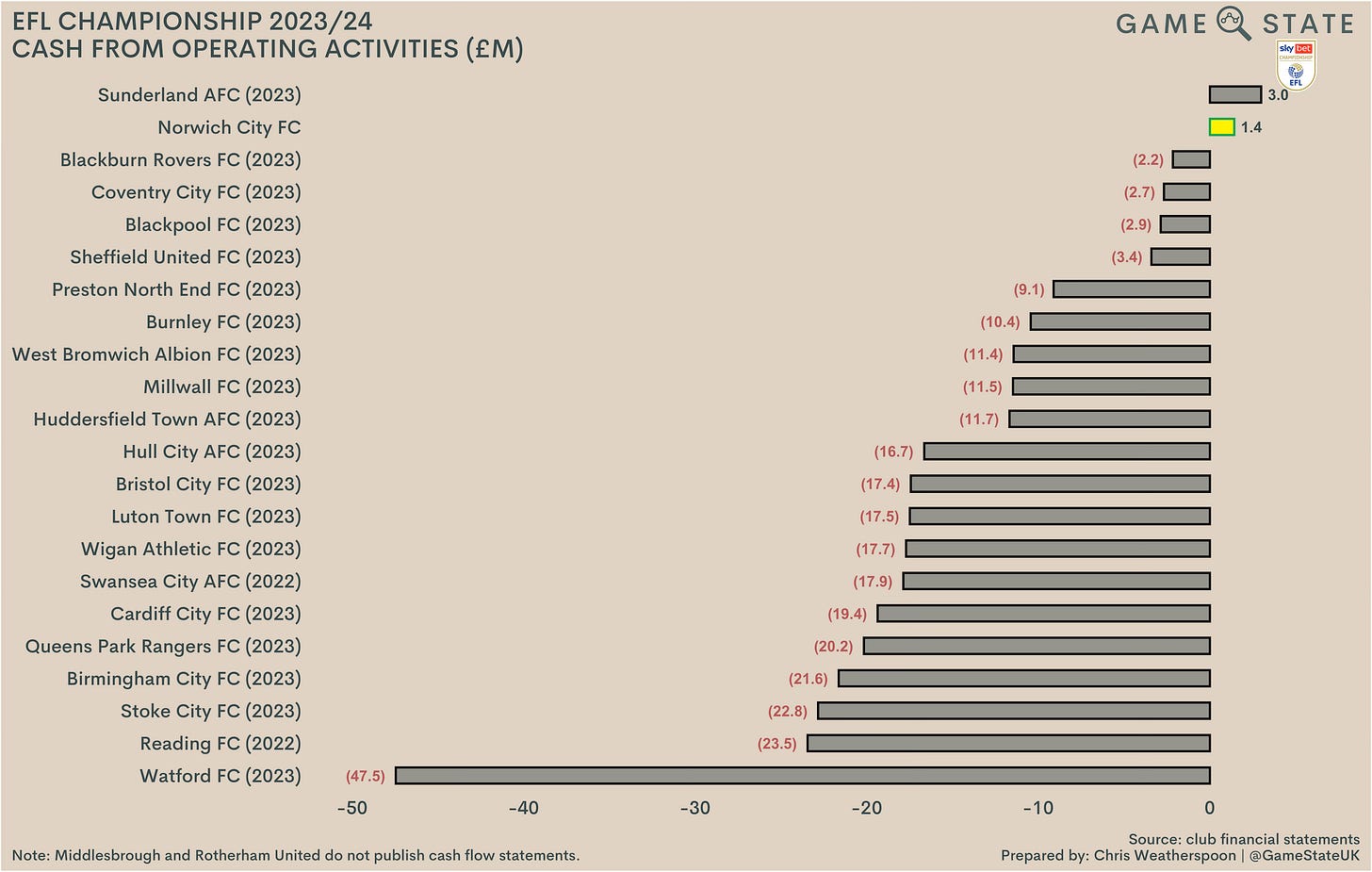

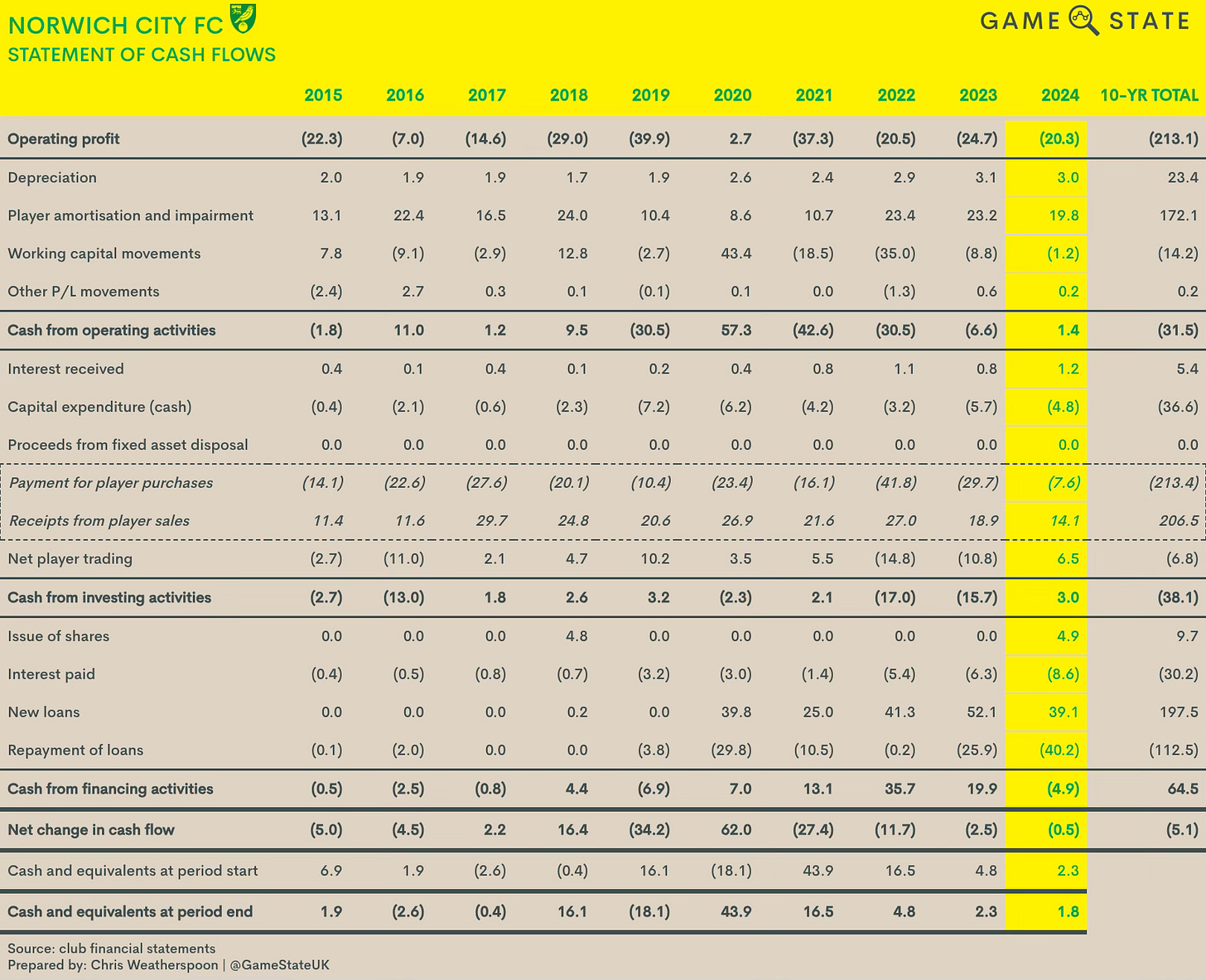

Cash flow

Norwich are actually only the second recent Championship club to post positive cash flow from operations, trailing Sunderland’s £3 million (Rotherham United were also likely cash positive from the day-to-day, but the club doesn’t produce a cash flow statement).

Most Championship clubs lose money from operations, and 15 of them lost more than £10 million in 2023, so Norwich’s result here is an undoubted positive. Of course though, it again shouldn’t be forgotten that the Canaries had a £39 million parachute payment last season; without that, they’d have joined the ranks of those losing hefty amounts in day-to-day cash.

Over the last decade, Norwich have received cash inflows of £95 million, split £85 million from loans (net) and £10 million share issues. In addition, the club utilised £5 million of its existing cash reserves. In turn, that £100 million has been spent on:

£37 million in capital expenditure on infrastructure;

£31 million covering operating losses;

£25 million net interest payments on loans and borrowings; and

£7 million net player trading.

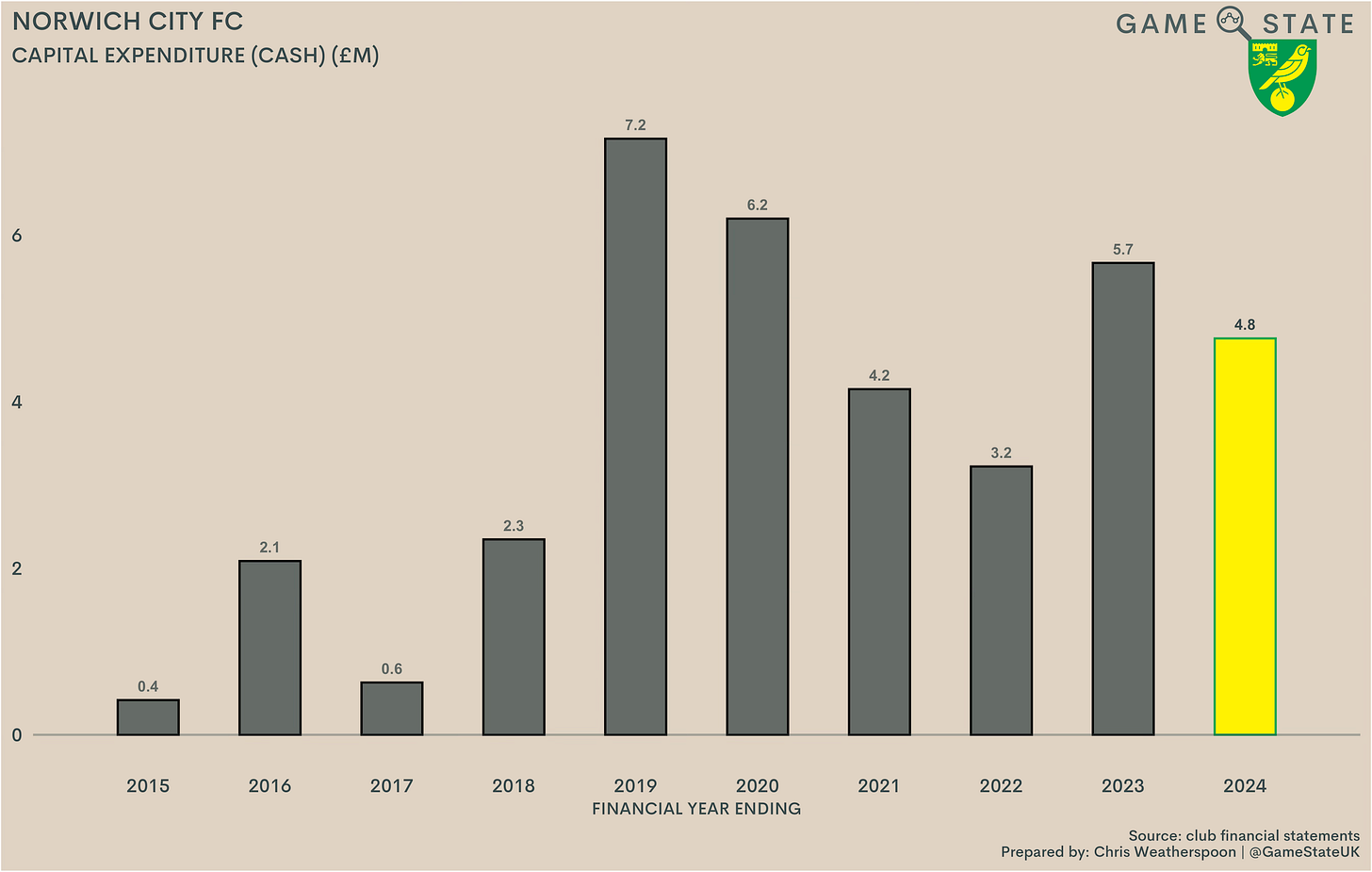

Unlike many clubs who’ve frequented the Championship, Norwich continued to invest in infrastructure throughout the last decade. Of course, they were buoyed by regular forays into the top tier, but it’s not always the case that EPL clubs spend their largesse on the long-term. That’s especially the case for clubs trying to avoid relegation, who generally funnel the bulk of their resource toward the playing squad in order to achieve that goal.

Indeed, it’s testament to the outgoing majority shareholders that investment in capital projects has spiked each time the club has been promoted. Of course, some will point to the fact Norwich were relegated each time at the first time of asking, and getting the balance right between long-term projects and short-term success on the field is clearly not easy, but it’s hard to think Smith and Wynn Jones ever had anything but Norwich City’s best interests at heart.

Capital spending in the Championship is fairly low across the board, with player costs eating up most of clubs’ day-to-day cash. The exceptions tend to come when clubs undertake one-off, large-scale projects, such as Queens Park Rangers’ new training complex and Luton Town’s impending move away from Kenilworth Road.

That makes Norwich’s willingness to spend £5 million on infrastructure somewhat more impressive, as the funds generally went towards improving assets rather than anything exceptional. The club’s Avant Training Centre was the beneficiary of some of that money, as were various lounges at Carrow Road, as Norwich committed funds toward improving fan experience on home matchdays.

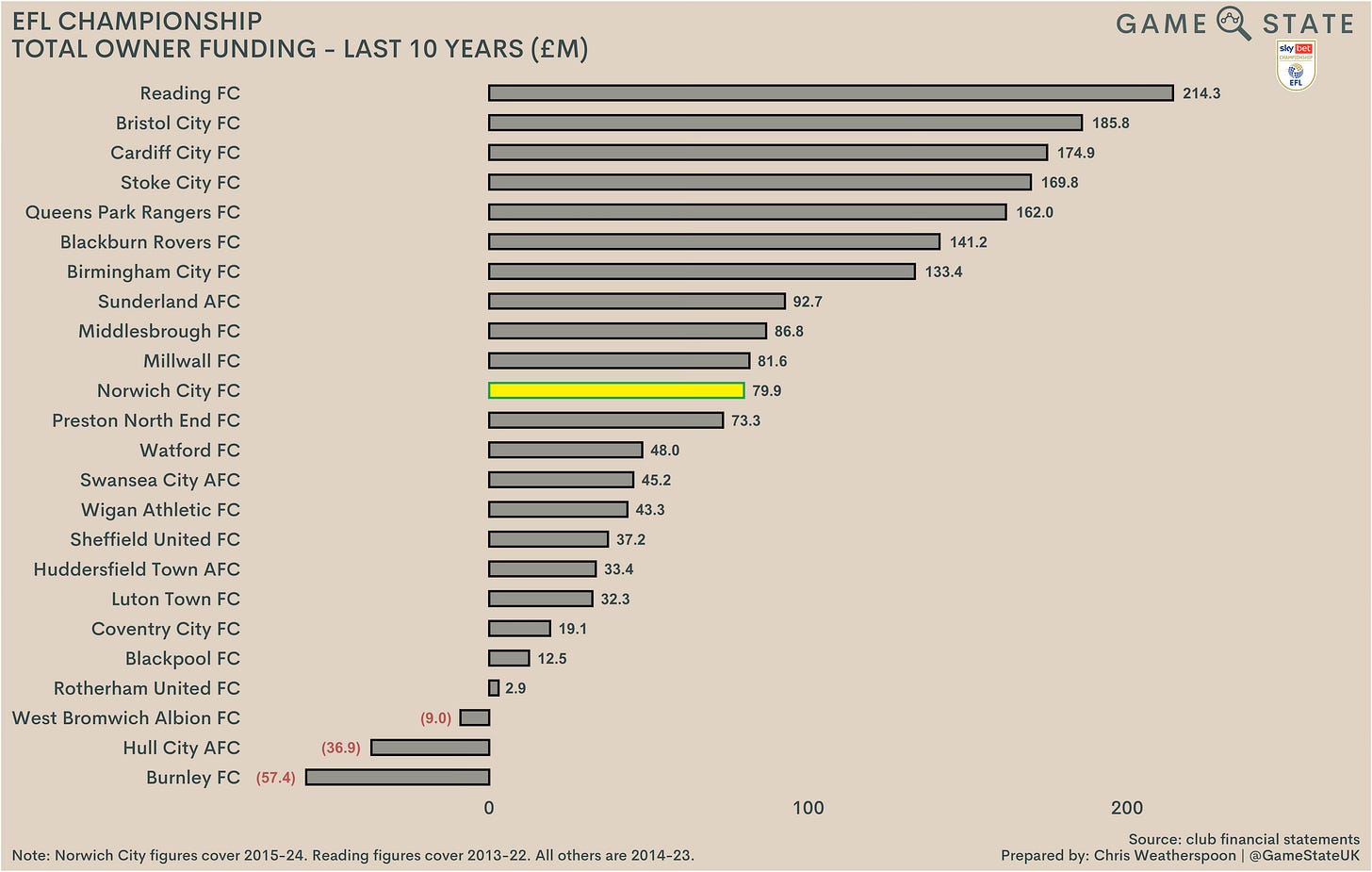

Owner funding

For many years, Norwich pursued a self-funded model, but that has changed since the arrival of Norfolk and Attanasio. In the last two seasons alone, Norwich have received £80 million in owner funding, split between preference shares (£10 million), loans (£65 million, £59 million of which has also been converted to preference shares since the accounting year end) and the raising of share capital (£5 million). Pretty much all of those sums have come via the hands of the club’s newest owners.

That has been a necessity. With EPL status once more lost and the long-run effects of the pandemic having tightened Norwich’s finances, Smith, Wynn Jones and other owners simply do not have the resources to prop up the club in the manner many other Championship owners do. In Attanasio they believe they’ve found a responsible owner to whom they can hand the reins, and with reported wealth of $700 million he should be able to foot the bills for a while yet.

Despite him only having been in situ for two years, Attanasio’s commitment has been extensive. The £80 million poured into Norwich since 2022 is the 11th-highest among Championship clubs over the past decade; if that commitment was to continue each and every year Norwich would soon outstrip everyone else when it comes to owner funding.

That’s unlikely to be the case, and the hope, both for the club and Attanasio, will be that investment can taper down as the club improves its operations and, ideally, returns to the top tier. Whatever happens in the future though, it’s clear Canaries fans have seen a marked shift in how their club is funded in recent years.

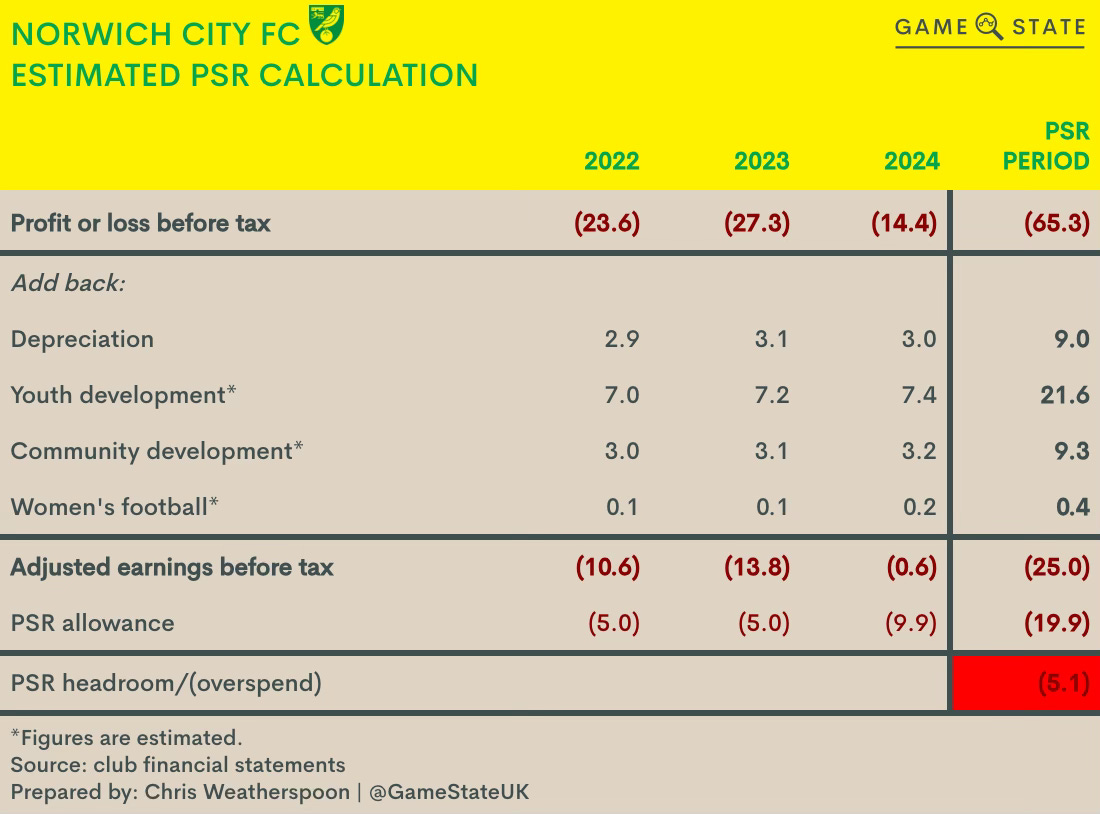

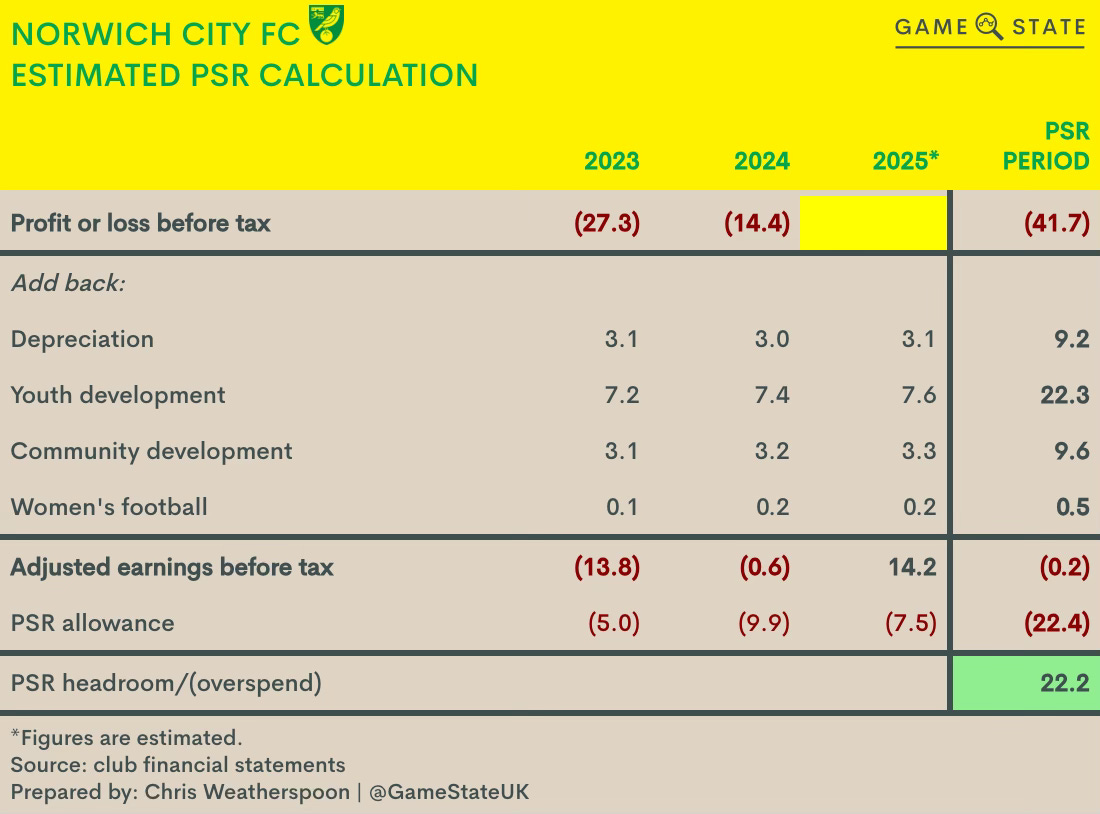

Profit and Sustainability Rules (PSR)

Norwich have had few historical problems when it comes to compliance with financial regulations, their generally decent results ensuring no real concern with the upper loss limits imposed on clubs.

Unfortunately, that’s another thing that has changed recently. Across the last three years Norwich have booked £65 million in pre-tax losses. That’s a big amount when it comes to PSR compliance in the Championship anyway, but it’s especially the case when we consider that the Canaries have received minimal equity funding (which increases a club’s loss limit), totalling just £4.9 million in the assessment period.

In fact, even using relatively generous estimates for deductible expenditure on youth development (Norwich’s academy is Category One) and community costs (the club is prominent in the local area and runs a number of outreach programmes), Game State’s model projects that Norwich would have failed EFL PSR last season by around £5 million. This is reliant on several estimates, and given there have been no reports of Norwich being under sanction or investigation then they almost certain passed in reality, but on face value it’s difficult to see how the club was compliant in 2023/24.

The answer perhaps lies in some of the funding provided by Norfolk and Attanasio. In 2023, Norwich received £10 million by way of preference shares which, if permitted to be included in their PSR calculation and expanding their allowable losses, would mean the club was compliant with EFL rules.

Yet the matter is a bit murky. Preference shares can comprise either debt or equity or, in some cases, a mixture of the two. The EFL only allows clubs to increase its loss limits by up to £8 million extra per season if those clubs are in receipt of ‘Secure Funding’, defined as follows:

The £4.9 million received in ordinary share capital in 2024 meets the definition of Secure Funding above (and so has been factored into Game State’s PSR model), but on public evidence there’s nothing to suggest those £10 million in preference shares do. Indeed, the club even lists that sum as a liability in the accounts, implying an obligation to repay Norfolk remains.

It may well be that the substance of the deal is different behind the scenes, and Attanasio and Norfolk have provided the EFL with a commitment to never redeem the shares. To our knowledge, Norwich haven’t been charged with any PSR breach, so it seems this is a non-issue, but it’s curious nonetheless.

Looking ahead to 2024/25, Game State’s PSR model projects that Norwich will be able to book pre-tax losses of £22 million and remain compliant. Our calculation includes the further £2.5 million in ordinary share capital that Attanasio is expected to convert his ‘D’ preference shares into in March 2025.

We expect that Norwich should be okay this season, even with the decline in broadcast income. The club’s wage bill has fallen, and the sales made in the summer transfer window translate to an estimated £20 million in player profits, which should ensure any loss in 2025 is below the level outlined above.

The future

The drawn-out departure of Smith and Wynn Jones from positions of prominence marks the entering of a new world for Norwich. For the better part of three decades, the pair have been purveyors of the club’s fortunes; their leaving is slow, but the direction of travel is clear.

How Attanasio runs the club from this day forward will be interesting to watch, but there are already some hints. The club’s transfer activity in the summer saw them book more net transfer income, with £30 million in sales surpassing the £17 million spend on new players.

That £17 million spend was noticeably directed at a younger market too; none of the four players bought for fees this summer were over the age of 21. That implies Norwich have picked up on a growing trend in football, whereby increasingly large fees are being expended on younger players. Norwich were also able to move on players for impressive fees, suggesting a shift to a more transfer-focused model, much like many other clubs have undertaken in recent years.

At the time of writing only 12 games have taken place in the 2024/25 EFL Championship season, but Norwich have gotten off to a decent enough start, losing only two of them. Left-winger Borja Sainz has exploded into prominence, notching 10 goals and two assists already, while the loan signing of Manchester City defender Callum Doyle could be an astute one. Doyle was a mainstay in Leicester City’s backline last season before a knee injury curtailed much of his season, and he lost in just two of 14 starts for the Foxes as they marched to the Championship title.

Norwich, Attanasio, Smith, Wynn Jones and plenty more will hope Doyle picks up another league winners medal this season. At this point it’s too early to suggest that will happen, or is particularly likely. But there’s been a noticeable shift at Carrow Road in recent years; from a self-sustaining club to one that found itself in a spot of trouble via both internal (transfer errors) and external (a worldwide pandemic) factors. The club’s debt remains high, any extended stay outside of the EPL will require even further owner funding, and there’ll need to be clarity around the path Norfolk and Attanasio now look to take, but there are hints of hope on the horizon in East Anglia once more.