Club financial analysis: Middlesbrough FC 2023/24

Game State's analysis of Middlesbrough FC's 2023/24 financial results.

Middlesbrough’s eighth-placed finish in the EFL Championship in 2023/24 meant the club’s Premier League (EPL) exodus would tick over into its eighth year this season, making this their longest stint outside of the top tier since the 1970s. Boro, who held much promise at the outset of last season under Michael Carrick, finished four points shy of a play-off berth despite losing just one of their final 12 league games.

Off the pitch, things took a downward turn too, with Boro posting a £12 million pre-tax loss. That was a shade under double their 2023 loss, and occurred even despite the club recording its highest revenues since their final EPL parachute payment landed in 2019. Turnover growth (13 per cent) outstripping wage growth (six per cent) meant Boro’s wages to revenue fell below 100 per cent for the first time in five years.

Though losses were up, the balance sheet looked rather better following chairman Steve Gibson’s decision to convert £149 million of outstanding loans into equity, with the club’s debt ultimately reducing by 91 per cent in the year.

Boro’s £12 million loss was primarily driven by player sale profits falling £5 million in comparison to 2023, though they still remained a healthy £17 million. In addition, Boro benefited from a £3 million legal settlement in 2023. Though the club’s income increased, it was offset by cost growth (both staff and non-staff), with those two items outlined above then pushing the club further into the red.

Profit and loss account

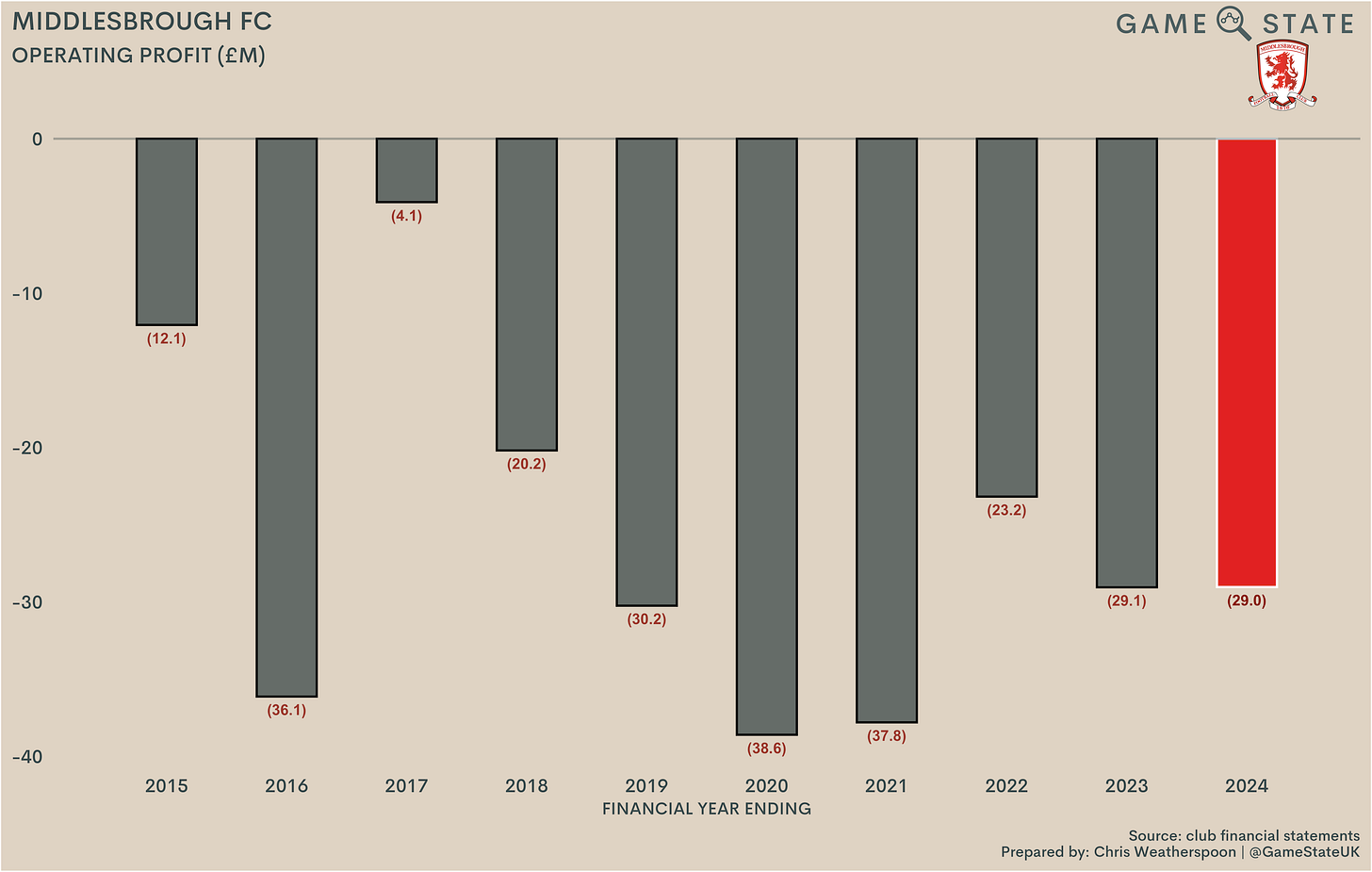

Being in the red financially is hardly unfamiliar ground for Middlesbrough: across the last 25 years, the Teesside outfit have managed to book a profit in just three seasons, the most recent coming in that final parachute payment year in 2019. Boro’s worst losses saw them record £30 million-plus deficits, first in 2016 as a result of bonuses paid following promotion, and then in 2020 and 2021 following the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic. In all, across the last quarter-century, Middlesbrough’s cumulative pre-tax loss is an eye-watering £349 million.

Of course, losing money in the Championship is hardly a novel concept; Middlesbrough are just one among many clubs who rack up huge losses in pursuit of promotion. Based on recently released figures from clubs in the division, Boro’s £12 million loss is the second tier’s 11th-worst, but they very much occupy a mid-table glut in this regard.

The losses incurred in the EFL Championship are staggering, and the fact all seven clubs to have published 2023/24 financials made a loss isn’t exactly a sign the tide is turning. Across the last decade, second tier clubs have posted combined pre-tax losses - after removing one-off exceptional items like owner loan write-offs - of £2.936 billion. With 17 clubs still to announce last season’s results, expect that figure to tick over the £3 billion mark some time very soon.

At the operating level, Boro’s losses are an order of magnitude worse. The club lost £29 million on the day-to-day in 2024, over half a million a week and largely in line with 2023. Last season was the seventh in a row, and eighth in nine years, where Boro lost over £20 million on an operating basis, which is a pretty good indicator of how much it costs to even just compete in the Championship, never mind actually get promoted out of it. Since 2015, Boro’s operating losses total £260 million.

While Boro’s pre-tax loss is middling for the second tier, their operating deficit is of greater concern. It’s currently the Championship’s third-worst figure, only ‘beaten’ by Sheffield United and Burnley (figures for both are from 2022/23). Those two were each recently relegated, meaning they had, in theory, plenty of saleable assets to boost the bottom line. While, as we’ll see, Boro haven’t done too shabbily in selling players themselves recently, the truth is the club will have to keep making strong sales in order to offset such mammoth operating losses - or rely on greater owner funding.

Turnover

Middlesbrough’s turnover improved for a fourth successive year, up £4 million (13 per cent) to £32 million. That’s a long way behind the £121 million of the last EPL season, reflecting the huge wealth disparity in English football, but it did mark a new post-parachute payment high for Boro.

That £32 million was the Championship’s eighth-highest income figure based on most recent financials. The five clubs in receipt of parachute payments were never going to be gazumped by the rest, but Boro sit third of the non-parachute clubs, only behind Bristol City and Sunderland. Other than possibly Stoke City and Ipswich Town, it’s unlikely any other non-parachute clubs will surpass Boro’s turnover once all 2024 financials are published.

Matchday income

Boro’s average league gate was a shade under 27,000 last season, the highest for a good few years. The club generally have some of the highest attendances in the Championship, though last season that figure was only good enough for sixth, as the division was littered with clubs with big stadia and the fanbases to fill them. Sunderland, Leeds United, Leicester City, Southampton and Ipswich Town all boasted a larger average gate than what was seen at the Riverside Stadium last year.

Boro’s gate receipts rose by 20 per cent to £11 million, entirely driven by the extra income generated from their run to the EFL Cup semi-final stage. Income from cup competitions totalled £2 million last season, while other gate receipts remained static at £9 million, in line with the largely similar average league attendance figure.

That £11 million is the Championship’s second-highest matchday income figure, only trailing Norwich City. That said, it is expected Sunderland will surpass one or both of those clubs once they release their accounts in late April or early May.

In any case, Boro’s stadium and fanbase do represent an asset worth having in the Championship, as a majority of clubs hover between the £5-7 million mark. Gate receipts in the second tier pale in comparison to those at the top end of the EPL, but there’s also a clear competitive advantage here for those clubs able to eke out higher amounts from match-going fans. Matchday income is no reliable barometer of on-pitch success, but it’s interesting that last season’s three relegated clubs - Huddersfield Town, Birmingham City and Rotherham United - each sit in the bottom four when it comes to Championship clubs’ gate receipts.

Broadcast income

Boro’s broadcast income has been static since their final parachute payment landed in 2019, and 2024 was no different, with only a slight (two per cent) increase to £10 million. There are no merit payments in the Championship, though that may change once the EPL and EFL finally agree on a new distribution model, so most clubs receive the same when it comes to TV income.

Middlesbrough received £5.19 million in the form of an EPL solidarity payment last season, which was paid to all Championship clubs not in receipt of parachute payments. On top of that, all 24 clubs received a £4 million distribution from the EFL pool, being the individual share of the annual amount the EFL earns from its TV deal with Sky Sports. A new TV deal cycle began in the current season, so both Boro and their fellow Championship clubs should see around a £1.8 million uplift in this payment as part of their 2025 financials.

There’s little use comparing Championship clubs’ broadcast incomes other than to highlight just how much more the parachute payment clubs receive. The rest of the division receives pretty much identical TV income, as detailed above, with any discrepancies generally arising from slightly different methods of categorisation in individual club accounts.

Middlesbrough’s share of the EPL riches has been limited to the solidarity payment for each of the last five seasons, a far cry from the £99 million distribution they earned during their 2017 relegation season.

After a sustained period in the top flight in the late 1990s and early 2000s, Boro have very much picked a bad time to spend multiple years outside of the EPL. The Teessiders have largely missed the boat coming in with respect to the huge TV deals generated by the EPL in the last decade; since 2015, Boro’s income from EPL distributions totals just £204 million. That’s less than the club would earn nowadays if they managed to stay in the EPL for even just two seasons.

Commercial income

Middlesbrough’s commercial income showed decent growth last season, up 17 per cent to a club record £12 million. With the exception of the Covid-hit 2020/21 season, Boro’s commercial revenues have risen steadily over the last five years, and now sit higher than the previous peak enjoyed in the 2016/17 EPL season.

There’s not much uniformity when it comes to clubs splitting out their commercial income into more specific categories, but from Boro’s accounts we know that £12 million was split £9.4 million sponsorship and commercial, £2.2 million merchandising. The latter remained static from 2023, but there was a £1.7 million increase in sponsorship and commercial, in part attributable to the arrival of BOXT as a principal partner, with the home services company providing Boro with sleeve and shorts sponsorship last season.

Boro occupy the top end of the second tier when it comes to commercial income, though there’s been recent significant growth at Bristol City, who now sit well ahead of the rest. Commercial income feels like one of the key untapped areas for many Championship and lower EPL clubs, and a club like Middlesbrough - with a sizeable fanbase and wide catchment area - could do worse than to increase their focus on upping merchandising income in particular.

Wages

Having reduced the club’s wage bill dramatically following relegation, 2024 was the fourth successive year of increase, this time with a six per cent rise to £31 million. That’s still less than half the amount Boro spent in their unsuccessful relegation battle in 2017, but it will be of some concern that the club finished four places worse off last season despite wage costs increasing by £2 million.

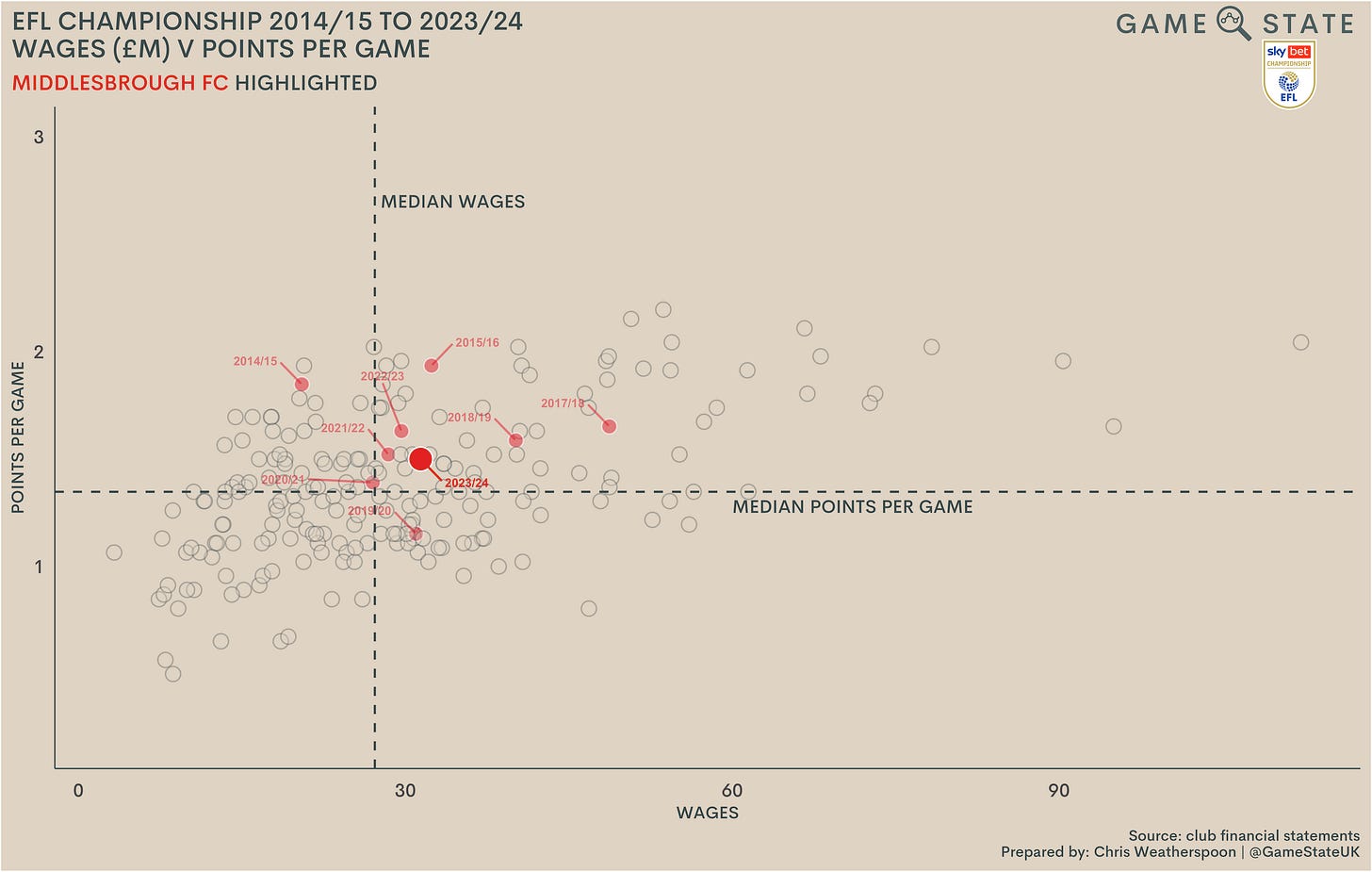

Wages are the most effective financial barometer of how a club will perform on the pitch, and based on latest figures Boro only slightly underperformed last season: their eighth-place finish was achieved with the division’s seventh-highest wage bill (based on most recent figures).

With only seven Championship clubs declaring 2023/24 financial results to date, that could change, but it’s a fact of life that Boro and many other clubs currently have to compete with a swathe of recently relegated clubs who tend to keep their wage bills high in pursuit of immediate returns to the Premier League. The combined most recent wage bills of the 24 Championship clubs came to £704 million.

At just over £30 million, Middlesbrough’s wage bill sits at the higher end of the non-parachute clubs, and the club has consistently paid more than the division median over the last decade. In fairness, they’ve also performed largely in line with their wage bill across the years, though there was a notable blip in 2020.

Comparing Boro’s wage bill ranking to where they finished in a given season shows they’ve generally performed to or slightly better than their staff costs each season since coming down, with the fairly glaring exception of their 17th place finish in 2020. Too few clubs have released 2024 financials to determine their over-/under-performance for last season, but finishing eighth looks likely to have been close to par again.

In terms of wage control, 2024 was the first time since the club’s parachute payments ran out that Middlesbrough brought their wages to turnover ratio below 100 per cent. Before any Teessiders jump for joy, the club’s staff costs still remained ruinously high relative to income, consuming 97 per cent of the £32 million turnover Boro booked last season.

High wages to revenue figures aren’t exactly rare in the Championship, but they’re only really possible to maintain year after year if one of two things is in place: strong player trading or beneficent owners. As we’ll soon see, Middlesbrough have employed a mix of the two, funding that wage bill both with some recent big player sales and the continued, seemingly bottomless generosity of chairman Gibson.

Spending 97 per cent of income on staff costs is by no means healthy, but so crazy are the finances of the Championship that nine clubs had a worse wages to revenue metric than Boro at last check. Luton Town led the way with 150 per cent, though that did include promotion bonuses. More worrying was Birmingham City’s 146 per cent, especially now they’ve since been relegated to League One.

Championship clubs with the lowest wages to revenue figures tend to be one of two things: clubs in possession of parachute payments or clubs in a relegation battle. There’s an argument here that as more and more clubs use player trading to bolster their financials, wages should instead be compared against an adjusted revenue figure, one that includes profits made from player sales. Doing so for Boro presents a much healthier figure of 64 per cent, but the transfer market provides a much more volatile source of income than clubs’ main revenue streams.

On a divisional basis, the Championship’s wages to turnover sits at 90 per cent based on latest figures, with those £704 million in combined wages eating up the vast majority of clubs’ combined income (£779 million). In effect, for every pound Championship clubs earn, after paying wages they only have 10 pence left for everything else they need to spend on. It is why so many second tier clubs are hugely reliant on benefactors.

Other expenses

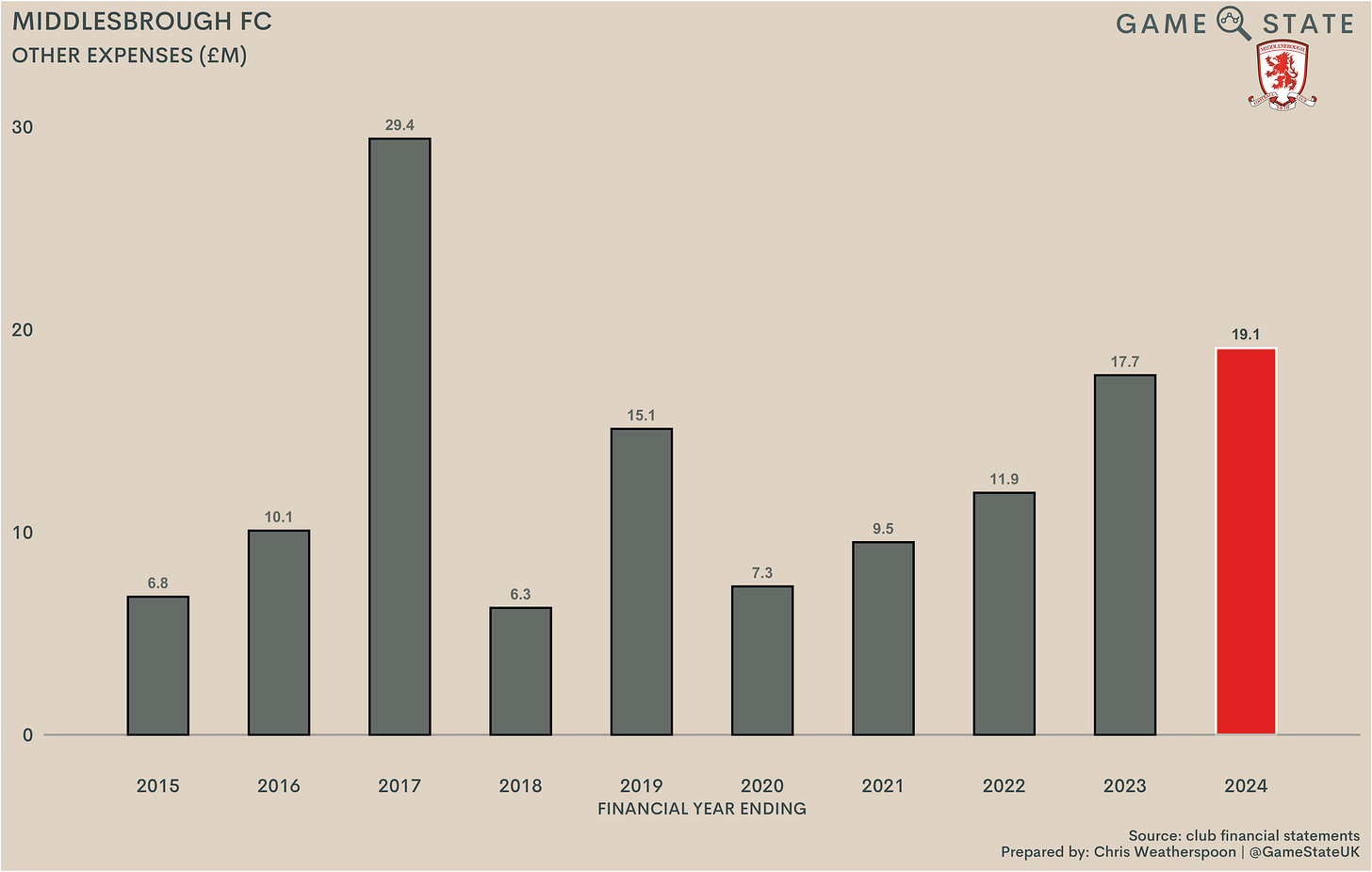

Middlesbrough’s other expenses (effectively non-staff costs, excluding depreciation) rose too, up eight per cent to £19 million. Across the board, clubs have seen these costs increase, with an inflationary environment being a direct contributor, and Boro’s increase isn’t out of step with non-staff cost increases noted at other clubs that have produced 2024 financials.

In relative terms, Boro’s non-staff costs are the division’s seventh-highest, coming in albeit a good few million behind the likes of Burnley and Sheffield United in 2023. It’s not too surprising - Boro have one of the bigger stadiums in the division and a Category One Academy to service and run - but it does also help highlight that without supplemental income from player sales or owner inputs, the club’s costs are much too big relative to the income they can generate in the second tier.

Evidence of Boro’s infrastructure being too big for a Championship can be seen when looking at non-staff costs as a proportion of income. In three of the last four years these costs have eaten up over half of the club’s revenue. When we consider that earlier we said Boro only had 10 pence of income left in every pound once wages were paid, it’s easy to see why losses remain high.

Tales of financial horror are legion in the Championship, but it’s also true that Boro’s other expenses to turnover ratio is one of the highest in the division. Stoke are some way out in front (72 per cent), but Boro are fifth for a metric you’d rather be low than high in. Of 24 second tier clubs, non-staff costs (again, excluding depreciation) ate more than half of income at 11 of them.

Player trading

Middlesbrough’s net transfer spend has fluctuated over the last decade, and it’s possible to see the club’s wider strategy and financial situation at a given time just by looking at their transfer activity since 2015. In the period 2016-18, the club spent heavily, first on promotion, then attempting to survive relegation, and then again on another promotion push. When the latter didn’t materialise they sold for more than they spent, and spending has remained modest (at least until last summer) during recent Championship years.

Last season saw Boro spend £19 million on new players, their highest outlay since 2018, but the club’s net spend was still (just) negative, owing primarily to the sales of Chuba Akpom (to AFC Ajax) and Morgan Rogers (Aston Villa). Across the last decade, Boro’s net transfer spend totals £56 million, though that expenditure is heavily front-loaded. Boro spent £94 million from 2014 to 2018; in the six years following they received £38 million more than they spent.

Based on disclosures in the latest accounts, another shift in strategy looks to be underway. With debt eradicated and no Financial Fair Play worries (two topics covered in greater depth below), Boro spent a net £16 million on new players in summer 2024, which is more than double their highest net spend of the last six years. While promotion has always been an aim for the Teessiders, that points to added impetus.

Boro’s biggest signing last season was striker Emmanuel Latte Lath of Atalanta, Lath having been under contract the Italian club his entire career but forever shipped out on loan. The Ivorian repaid Boro’s faith in him with a stellar opening season, notching 16 goals while playing the equivalent of just 23 full league games. At the time of writing, he’s already notched another 10 this season. Finn Azaz, signed from Aston Villa’s under-21 team, has proven another astute buy too.

On the flipside, Boro sold Chuba Akpom and Morgan Rogers for chunky fees, the latter after just half a season at The Riverside. The Rogers transfers are an example of excellent work in the transfer market, Boro having only bought him for £1 million before selling him for eight times that (with a potential further £8 million in add-ons), though Manchester City do retain a 25 per cent sell-on clause regarding any profit Boro make on Rogers.

Middlesbrough are the highest spenders of the seven Championship clubs to publish their 2024 accounts to date, and they’ll remain high up the list once all 24 clubs do so. Burnley’s figure is misleading here, as much of their 2023 spending took place after promotion had been achieved (their financial year runs to 31 July). Boro spent big for a second tier side, notably spending £10 million more than the likes of Norwich City and Hull City.

Of course, some of that spending was made possible by a strong selling performance. Based on most recent numbers, Boro’s £20 million from sales last season was the fourth-highest in the Championship. Watford’s huge £76 million was made possible by them selling players with EPL experience, something we’ll see relegated when Leeds United, Leicester City and Southampton release 2023/24 financials.

As a result of Boro’s transfer activity, transfer fee amortisation grew 15 oper cent to £9 million. That’s still a way off the £25 million seen around the turn of the decade, but it is also a 50 per cent increase in two years, reflecting the club’s clear strategy to ‘go again’ in pursuit of a top tier return.

Recently relegated clubs dominate the amortisation rankings, especially when they choose to keep hold of players signed in the EPL for sizeable fees. Even so, Boro’s player amortisation costs are next in line, and nearly double those seen at Hull. Many Championship clubs struggle to spend a lot on transfers as wages take up much of their cash, so Boro are a rare instance of a club that commit chunky amounts to both.

Many clubs have had to move toward utilising player trading more heavily in their business models, and Boro are no exception. They’ve booked nearly £40 million in player profits in the last two seasons alone, which is good going for a Championship club that doesn’t have any recent EPL players on its books (or at least not ones who played in the EPL for Boro). The sales of Akpom and Rogers were the main drivers of 2024’s profit, with the £7 million profit on the latter particularly impressive given he was only on Teesside for six months. Across the last decade, Boro’s bottom line has been boosted by £116 million in player sale profits.

Boro’s player profit figure is the second-highest of the seven Championship clubs to publish 2024 accounts, though they’ll fall a few spots when 2023’s relegated EPL clubs publish theirs. Still, £17 million marks a really strong result for Boro, particularly given they’ve been back in the second tier for so long. Of clubs that haven’t recently been in the EPL, only Bristol City, who’ve proven themselves excellent at generating money from player sales, made a greater surplus from this income stream (£22 million).

Squad cost

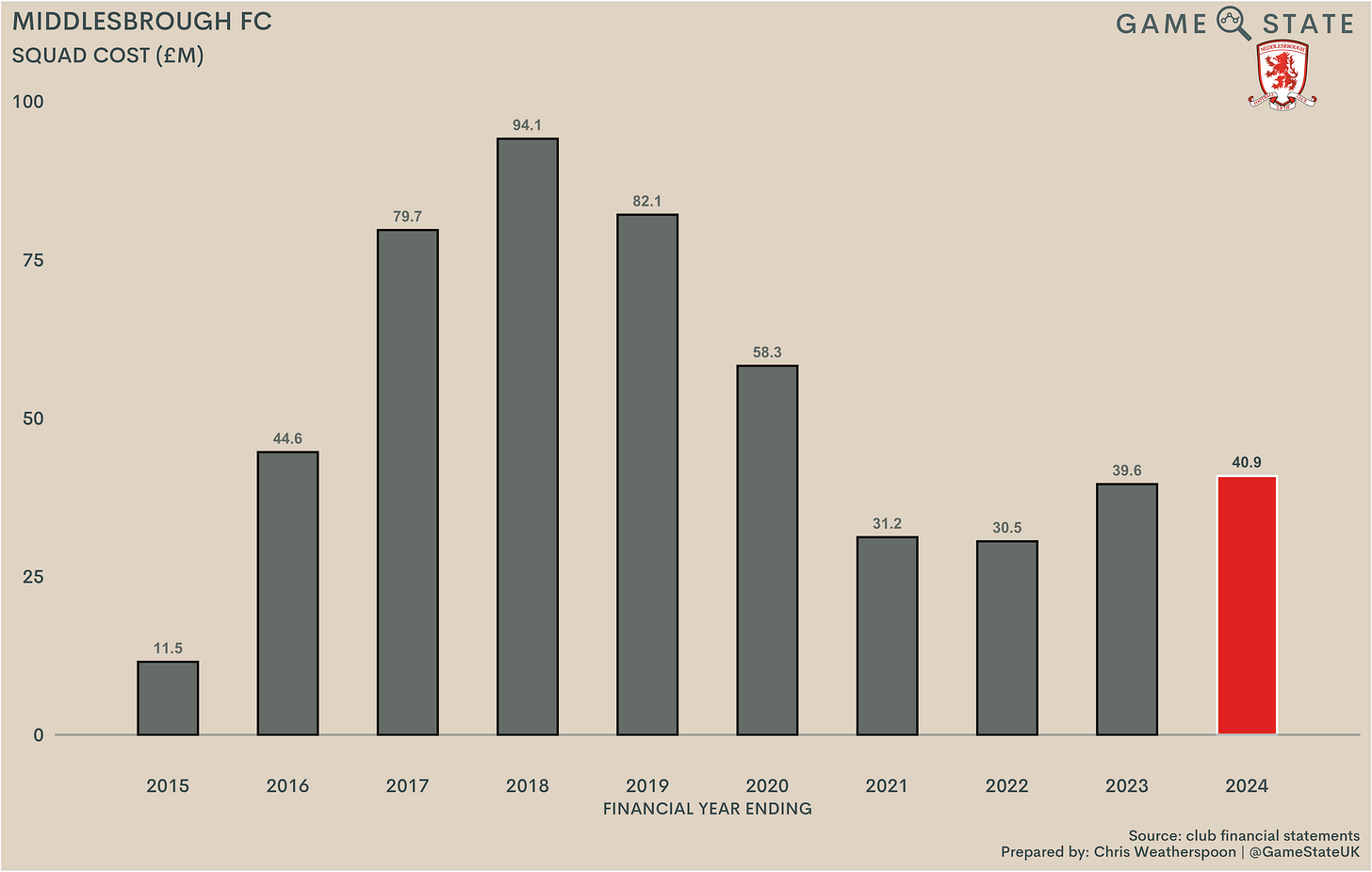

The result of that transfer activity was Middlesbrough’s squad cost - i.e. the amount it cost the club in fees to assemble the playing squad - totalled £41 million at the end of June 2024. That’s gone up around £10 million in the last two years, but is less than half the peak of £94 million in 2018.

Notably, Boro’s squad cost was higher in the year following relegation than the year they were in the Premier League, which reflects both their (unsuccessful) attempt at a swift return and the surge in transfer fees at the top end of English football.

For all Boro’s net transfer spend has been low in recent years, that’s not for want of new signings. In fact, Boro’s current squad cost is the sixth-highest in the Championship, only trailing five clubs who have all been in the EPL more recently than them.

Many second tier clubs struggle to splurge too much on transfer fees, as wages eat up just about all of their available resources. Boro aren’t exactly big spenders comparative to EPL teams, but Michael Carrick does have at his a disposal a squad that has cost more to assemble than most.

Balance sheet

Football debt

Middlesbrough’s net transfer balance (amounts owed by clubs from sales less amounts due to clubs on purchases) has been negative across the last decade, and remained so in 2024, with their net transfer debt rising a smidge to £6 million.

Not all Championship clubs disclose transfer receivables and debts but, of those that do, Boro’s net payables of £6 million were the league’s second-highest, only trailing Burnley (whose balance is misleading, much like their player additions total detailed above). Echoing the fact many Championship clubs don’t have much left over for fees, quite a few have a positive net transfer balance.

Financial debt

Middlesbrough’s debt was slashed in the year to £24 million, the club’s lowest gross debt figure this side of the millennium. That debt was split £10 million to Macquarie Bank, an Australian lender who specialise in providing football clubs with advanced financing on transfer fee receivables, and £14 million due to Gibson (via The Gibson O’Neill Company).

That £10 million owed to Macquarie relates to the sales of Marcus Tavernier to AFC Bournemouth and Chuba Akpom to AFC Ajax. At the end of June, Boro were due £5 million of the £10 million they sold Tavernier to The Cherries for in August 2022, and around €6.8 million from Ajax for Akpom, who bought the striker for €12.3 million in August 2023. Macquarie will be repaid when instalments on those deals land, £6 million of which came in after the 2024 financial year end in July and August, while the bank also receives a slice of interest in exchange for providing Boro with advance financing.

The remaining £14 million incurs no such financing costs, in keeping with most of the loans Gibson has provided to the club during his time in charge. Gibson wrote-off pretty much all of the previous debt due to him midway through last season, but Boro’s ongoing losses meant he was required to inject a further £14 million last season alone.

That sum covered the club’s annual loss. In other words, without the support of Gibson through The Gibson O’Neill Company, the football club would either have to obtain external funding (at, no doubt, a hefty rate of interest given ongoing losses), massively reduce expenditure on players (and therefore struggle to compete in a league where nearly every club loses money in pursuit of promotion), or cease to exist at all, as they nearly did in the mid-1980s before Gibson and others arrived to save them.

It seems strange to say it but the day-to-day effect of that huge debt write-off was fairly negligible. Boro paid no interest on the loans to Gibson, so removing the obligation to repay those loans didn’t really impact how much cash the club had for other things, though it did strengthen the balance sheet and improve the club’s Financial Fair Play headroom (as equity contributions increase Championship clubs’ loss limit by up to £8 million per season).

In one swoop, that debt eradication removed Middlesbrough from the top of the Championship debt table; they now sit 10th from bottom, and the next most indebted club, Preston, hold double the debt Boro do (even as Preston were themselves beneficiaries of a £50 million owner loan write-off last season). In all, even despite the recent generosity of owners like Gibson and The Hemmings Family at Preston, Championship clubs’ combined gross debt totals £1.42 billion.

Investment and funding

Middlesbrough are one of the few clubs in England’s top two divisions to not publish an annual cash flow statement. The club’s shares are held by chairman Steve Gibson’s primary business, Gibson O’Neill, so the football club qualifies for an exemption when it comes to publishing its cash flow.

Gibson O’Neill brings together Middlesbrough FC, Bulkhaul, a chemicals transportation company, and Rockliffe Hall, a luxury hotel and golf course (which sit across the road from Middlesbrough’s training ground and Academy), so trying to extract the football club’s cash flows from the group’s accounts is a futile endeavour.

Even so, we can still glean some details around investments made by the club and the extent of Gibson’s funding.

In terms of capital expenditure, Boro haven’t spent all that much since coming back down to the Championship in 2017, having used that EPL year and the attendant riches to invest over £6 million then. That said, the club spent over £3 million in 2024. What that went on is unclear, but Boro boast good facilities that aren’t especially old, and it’s hard to say they’ve skimped in infrastructure.

QPR’s £12 million on their new training ground stands out when it comes to capex in the Championship where, for the most part, clubs don’t spend all that much on infrastructure. That’s again because after wages there’s not much money left for anything else, so it’s testament to Boro and Gibson that the club last season spent fairly big amounts on not just wages and transfer fees but on capital projects too.

Owner funding

Gibson has long been viewed as one of English football’s most generous - or patient - benefactors, and last season did little to dispel the description.

Having first converted £149 million of existing loans to equity, both reducing club debts and maximising Boro’s potential losses under EFL financial rules, he also continuing to pour cash in, much as he has for the last three decades. 2023/24’s commitment was a further £14 milllion, more than double what was required in 2023, taking Gibson’s funding of the club in the last decade to £94 million.

Determining the full extent of Steve Gibson’s commitment to Middlesbrough over the years isn’t the easiest exercise, not least because it requires nearly 40 years of accounts trawling. As well, Boro’s lack of a cash flow statement over much of that period means we’re reliant on looking at balance sheet movements.

Even so, the extent of the chairman’s financial support is clear: up to and including the £14 million provided to the club some time after June 2024, Gibson has provided £270 million of funds to Middlesbrough during his time at the helm. Leaving aside any interest that may have been paid in the early days (more recent loans have always been interest-free; older ones may have incurred some cost to the club, but it’s not easy to tell from the accounts whether that’s just an accounting entry or actual cash paid), the only time Gibson has taken any of his money back was in 2007, when £69 million of shareholder loans were replaced by bank debt. That was soon reversed. Within four years, that amount and more had been put back into the club.

Gibson’s love for the club is well-known, and backed up by his wallet. Little wonder some Boro fans refer to him as owning the world's most expensive season ticket.

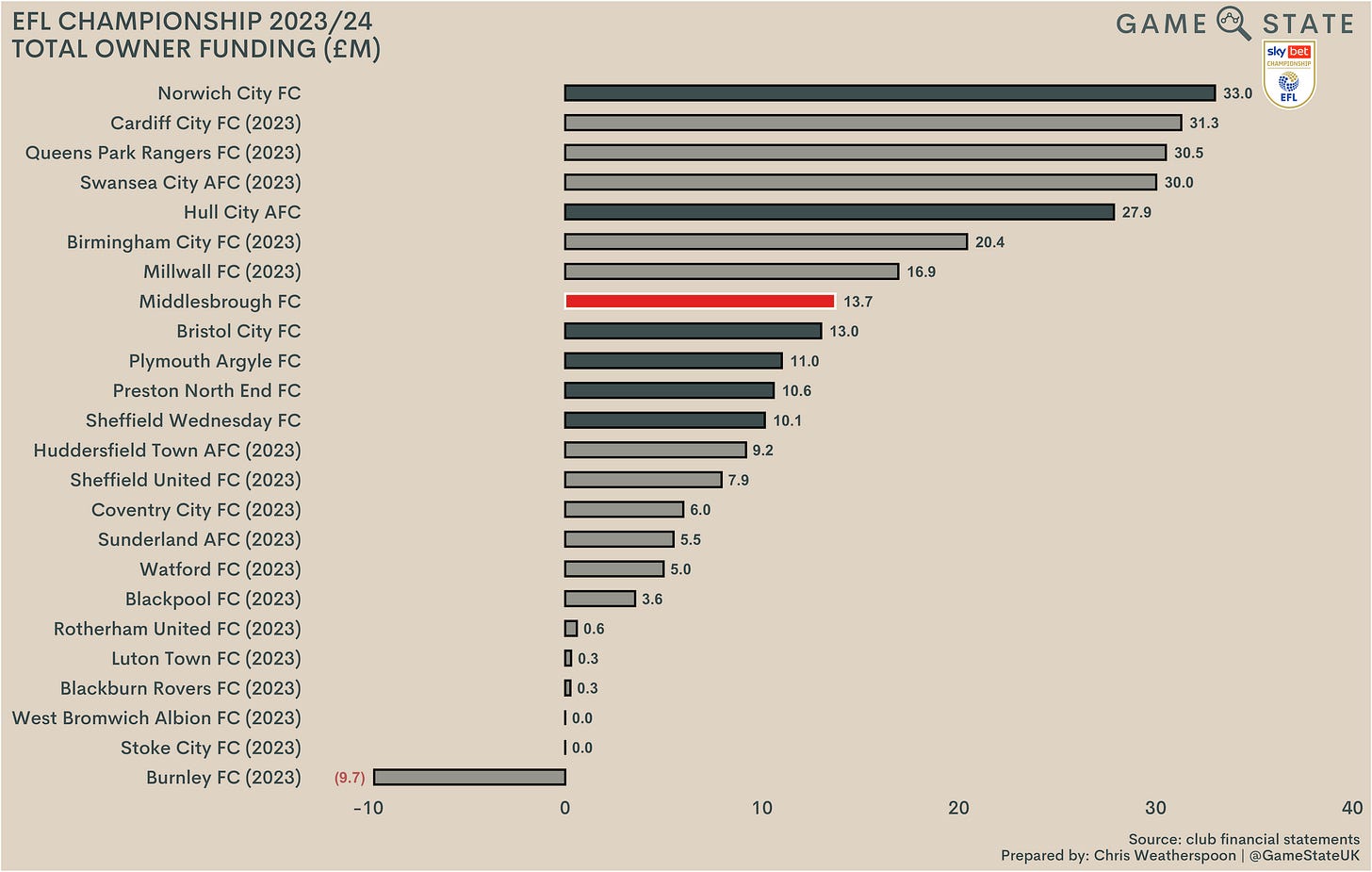

Looking at owner funding in single-season isolation isn’t all that useful, but it does help highlight just how much Championship clubs rely on their shareholders. Including the £14 million Gibson put into Boro last season, total owner funding in the Championship per latest club accounts stood at £277 million per year, and that includes the £10 million Burnley’s owners actually took out of the Turf Moor club in 2023.

Gibson’s 10-year commitment of a shade under £100 million is a lot of money to spend nine of those 10 years in the second tier, but there are some even scarier figures bouncing around when it comes to shareholder contributions to clubs. Of recent or current Championship clubs, Reading’s £214 million owner funding from 2013-22 (and they’ve not even published accounts since 2022, so a more up to date figure is likely even higher) leads the way, but the likes of Bristol City (£191 million), Cardiff City (£175 million), Stoke City (£170 million) and QPR (£162 million) have all relied on huge sums from their owners in the last decade.

Profit and Sustainability Rules (PSR)

Middlesbrough have booked £38 million in pre-tax losses over the past three seasons, a figure which at first glance runs them right up against the £13 million per season allowable limit for Championship clubs. That limit would have been just £5 million per season were it not for Gibson converting debt to equity.

Of course, that £38 million figure is just a starting point when it comes to PSR calculations. Boro, like any other club, can remove from their calculation what the EFL deems allowable expenditure, namely spending on fixed assets, youth and women’s football and community causes.

Like every other club in the country bar Ipswich Town, Boro don’t disclose their PSR calculation, but there’s enough information out there to make an informed estimate. While Boro’s losses are sizeable, it’s key to remember that the club’s Category One Academy eats up some hefty annual costs. Academy expenditure differs across clubs even if they sit in the same category, but Boro’s costs here are generally agreed to be at least £5 million a year.

Removing those costs and other allowables, Game State’s PSR model projects that Middlesbrough’s PSR loss for the 2021/22 to 2023/24 three-year period was £12 million, or £27 million under the club’s loss limit for that timespan. In other words, Boro had few worries about PSR compliance last season.

The same is true of the current season too. This year’s calculation sees 2022’s £20 million pre-tax loss (or, per our model, an £11 million PSR loss) drop off Boro’s calculation, meanwhile the EFL’s decision in the summer to grant clubs a £2.5 million cost of living allowance has, in effect, replaced the Covid-19 allowance that was permissible in 2022.

A calculation for this season is even more heavily reliant on estimates, but Game State’s model projects Boro are far away from any PSR-related troubles this season. We estimate the club could lose nearly £50 million pre-tax in 2024/25 and still meain compliant with the EFL’s financial rules.

The future

Finishing eighth last season was a disappointment for Boro, Gibson, Carrick, players and fans alike. After a lull when the club’s parachute payments ran out in 2019, Middlesbrough have begun investing more heavily in the playing squad once more spending £10 million-plus on new players in each of the last three seasons.

Last summer’s transfer activity ensured that streak stretched to four, with Boro spending a net £16 million on new signings. At the time of writing, that net figure has dropped by up to £5 million, following wideman Isaiah Jones’ departure for Luton Town in January. Even so, it’s clear Gibson and Boro are far from giving up on promotion and, having manoeuvred themselves into a favourable PSR position, have no qualms bolstering the squad yet further.

(Note that the table above suggests quite a large discrepancy between reported fees and the amounts disclosed per Middlesbrough’s latest accounts. Two summer signings, Aidan Morris and Delano Burgzorg, were announced in June, so have been included in our 2023/24 table earlier in this piece. Shifting them to the post-June table above would largely reconcile reported fees with the accounts, but would open up a similar gap in the 2023/24 numbers. Therefore for clarity we highlight that the total amounts paid per the accounts and our tables are correct but, as clubs do not disclose individual fees, the specific transfer fees noted within those tables should be treated with caution.)

At the time of writing, Boro sit fifth in the Championship after 26 games. Problematically, there’s a nine point gap to fourth-placed Sunderland; nine points the other way encompasses eight separate clubs on Boro’s heels. So far it’s been a season of wastefulness for the Teessiders, with chances going begging during many a dominant performance. In recent weeks that dominance has waned, but their opponents have been nowhere near as wasteful as Boro have been for much of the season to date.

A loss to Blackburn Rovers in the third round of the FA Cup does at least mean Boro can focus on their promotion push, but from a financial point of view the club will rue no repeat of last season’s EFL Cup run (they were dumped out in the second round this year). Cup runs have provided a necessary boost to Boro’s gate receipts in recent years, though a roughly £2 million annual uptick in distributions from the new EFL TV deal starting this season should soften much of the blow.

How things will go on the pitch in the latter half of the season is anyone’s guess, but from the current vantage point another chunky loss looks likely for Boro this season. The departure of Paddy McNair and his reported £20,000 weekly wage will soothe the wage bill somewhat, but Boro’s activity in the transfer market makes wage savings unlikely and will further increase transfer fee amortisation costs. Even with the sale of Isaiah Jones this month, Boro’s net transfer spend is set to be their for seven years.

Promotion is clearly the aim and, in some ways, an increasing need. Steve Gibson was a young man when he helped save Middlesbrough from extinction, and while he’s still only 67 years old now and there’s no sign of his appetite for chairmanship and funding the club waning, there will come a time when his football club are no likely able to rely on him. That could be decades away, and hopefully for Boro it is, but for all Gibson’s munificence has ensured the club is safe from trouble, repeated heavy losses are hardly desirable.

Middlesbrough are on more solid footing following the debt write-off, and income has started to rise. The club’s player trading has reaped solid profits in recent years. But without promotion they’ll forever be in need of a generous owner.