Club Financial Analysis: Derby County FC 2023/24

Game State's analysis of Derby County FC's 2023/24 financial results.

After touching the abyss, the 2023/24 season was one replete with the joys many Derby County fans likely wondered if they’d ever experience again. In their second season under new ownership following a flirtation (okay, it was an outright affair) with disappearing completely, The Rams finished second in EFL League One, notching up 92 points and ending their two-year stint in England’s third tier.

Off the pitch, Derby’s pre-tax loss loss dropped by 30 per cent, down from £20 million to £14 million. That isn’t really reflective of the football club’s underlying performance though, given over £9 million of 2023’s deficit owed to an impairment of goodwill arising from the successful purchase of the club out of administration by David Clowes, a multi-millionaire Derby County fan.

Excluding that goodwill impairment means the club’s underlying loss actually widened by £3 million (28 per cent) in 2023/24, though of course that did come alongside promotion, so there’ll be a feeling it was money well spent.

The increase was primarily driven by the club’s wage bill increasing over a quarter from 2023, while non-staff costs rose too. Income fell by five per cent, though the overall loss was mitigated by a £3 million improvement in player profits, principally from the sales of midfielders Jason Knight and Max Bird to Bristol City.

Profit and loss account

Clubs and businesses in financial trouble often throw up numbers that don’t really track to the reality of their impending doom, and Derby were little different. Their final year of accounts under Mel Morris’ ownership actually presented a £15 million profit, which seems surprising given they tumbled into administration a couple of years later.

It’s less surprising when we accept that £15 million profit was the result of Morris finding a new way to funnel money into a club already in trouble when it came to complying with the EFL’s financial rules. That surplus in 2018 included a cool £40 million worth of profit from, at least as it seemed at the time, the club selling its home stadium to itself (or, legally, to a separate entity also wholly-owned by Morris) in exchange for an £81 million cash boost, a loophole the EFL had to close when several other clubs opted for a similarly short-termist tactic.

The short-termism of it was laid painfully bare when crisis arrived; having put the club into administration, Morris ceded control of the sale process, but Gellaw Newco 202 Limited, through which he’d bought Pride Park, remained in normal operation. Morris

subsequently used the ground as his only remaining leverage in eking out at least a small sum to offset against the huge amount he lost on owning Derby.

In any case, removing that ‘exceptional’ stadium sale shows a truer figure for 2018: a loss of £25 million. Similarly, 2023’s pre-tax result included that £9 million goodwill impairment; its removal seems sensible here.

Doing so still highlights just how ruinous the last decade has been for Derby, even with losses almost half what they were. In the six years covering 2015 to 2018 and 2023 to 2024, The Rams lost £99 million. Per the administrator’s progress report in 2022, the club had a further trading deficit of £13 million in the year to 21 September 2022, taking the total to £112 million - and that’s without knowing the extent of the deficits incurred in the three and a bit years from July 2018 to September 2021.

Derby are the first League One club to publish 2023/24 financials, so there’s little in the way of comparable data available for last season. Using most recent figures is at least indicative; Derby’s £14 million loss was the division’s second-highest, usurped only by free-spending Ipswich Town in their own promotion year in 2023.

The finances of League One aren’t as perilous as the madcap Championship, but they’re still not very good. Only two clubs booked a profit in 2022/23, and those figures combined were just £2 million. The remaining 22 clubs’ most recent figures, inclusive of Derby’s latest loss, came to a combined deficit of £98 million. While most clubs made losses in the £2-3 million range, Derby and Ipswich combined for nearly a third of the division’s overall deficit.

At the operating level, the picture was actually worse. The Rams lost £19 million, up from £13 million in 2023 and reflective of increased wages (partly due to promotion bonuses) and dips in two of the three main revenue streams. Across the six most recent years for which we have figures, Derby lost £126 million at the day-to-day level, an average loss of £404,000 per week.

In fairness to Derby, all League One clubs lose money at the operating level, and the ‘bigger’ clubs tend to lose more than everyone else. The costs of running big grounds like Pride Park and other attendant facilities take up a huge proportion of revenue due to the relative lack of TV income in the lower tiers, so it’s no surprise that Derby’s day-to-day loss was nearly the division’s highest (and, again, probably will be once we know a full slate of 2024 financials).

Not all League One clubs publish detailed income statements but, of the 18 that did, all of them lost money at the operating level. In total those clubs combined for an annual loss of £105 million - more than £2 million a week.

Turnover

Derby’s revenue fell £1 million last year, down to a decade-low of £19 million, and £10 million below the final season we have data for under Morris. That’s a big drop but also an expected one, as there’s a sizeable drop-off in TV money between the Championship and League One.

More surprising might be the drop in income in a promotion year. However, that £1 million fall came from a couple of things unrelated to Derby’s league performance. Their first-year parachute payment from the EFL, given to clubs relegated from the Championship, reduced, while the club’s exiting of both the FA and Carabao Cups in the first round - having reached the fourth and third rounds respectively in 2022/23 - saw income from those competitions reduce too.

Derby’s income trailed Ipswich by a couple of million, though it’s expected that they’ll top the table once all results for 2023/24 are published. There’s a fairly clear gulf at the top of League One when it comes to income, as clubs with historically large fanbases (and ones who generally expect to be competing in a higher division) are able to generate bigger sums from multiple revenue streams.

Derby’s income last season was actually the 10th-highest in English third tier history, though some way behind Sunderland’s record £59 million in 2019, when they received a £35 million parachute payment (albeit the bulk of that was used by their former owners to facilitate a purchase of the club). Derby’s income in 2023 was the ninth-highest such figure, and ensured they joined a group of only five clubs to have recorded more than £20 million turnover while in League One, though the expectation is Wrexham will increase that number to six this year.

Matchday income

For all their recent travails, Derby’s support has held up well. Pride Park has routinely been over 80 per cent full across the last decade (Covid-impacted years excluded), and last season was little different, as The Rams averaged 27,278, the highest in League One. That tally was also higher than all bar four EFL Championship clubs, and more than six EPL clubs, meaning Derby averaged the 19th-highest gates in England last year, which is pretty impressive for a club in the third tier.

That still translated to the club’s lowest gate receipts in a decade, though that’s perhaps not surprising - charging fans a premium for a lower standard of football wouldn’t wash, and especially not after what Derby supporters have been asked to put up with in recent years.

Unsurprisingly, Derby’s matchday income was one of the highest in League One, and likely will be the highest once all results for 2024 are published and Ipswich drop off our list. There’s significant variance across the division when it comes to gate receipts, reflecting how England’s third tier is at once the refuge of fallen giants and clubs who have routinely occupied the lower reaches of the league pyramid.

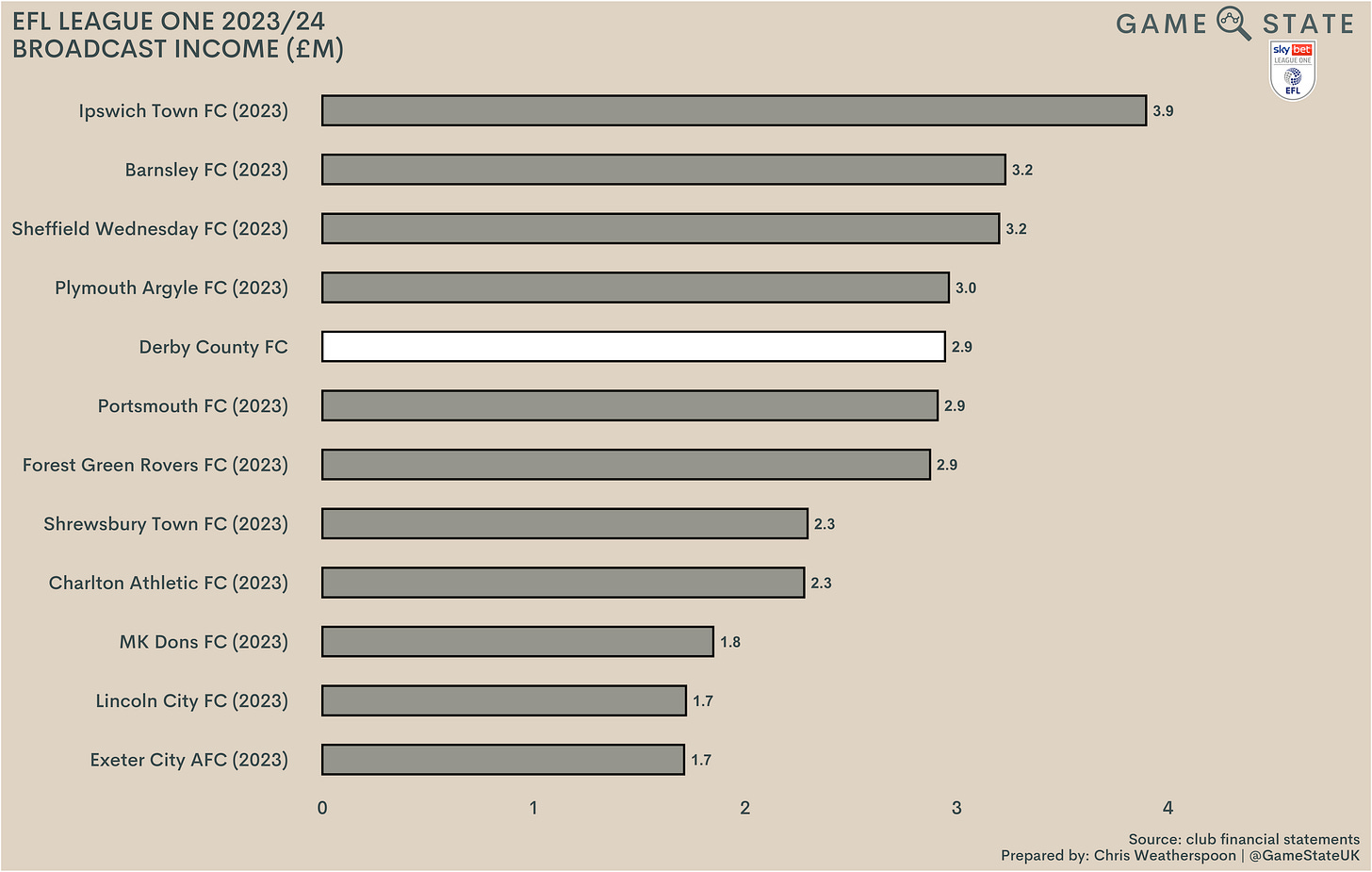

Broadcast income

Derby also saw TV income drop last season, down almost a quarter to just £3 million. That’s the lowest level in a long time at Pride Park, reflecting the impact of relegation to the third tier. Having failed to return to the Championship at the first attempt, Derby saw their EFL parachute payment (a lesser-known and much lower value payment than its EPL brother) fall, while a lack of progress in the domestic cups ensured both less prize money and no repeat of knockout games being televised like their tussles with West Ham United and Liverpool were in 2022/23.

Broadcast income in League One is much of a muchness, covering a fairly small range. That might change this season following the commencement of the EFL’s latest TV deal, which has resulted in far more third tier games being televised than ever before.

Following promotion, Derby obviously won’t need to worry about the deal’s impact on League One, but they should see a significant increase in broadcast income in 2024/25, both from a larger share of EFL distributions and from an increase in the solidarity payment flowing down from the EPL. In League One last season the latter was around £0.8 million, whereas Championship clubs will each receive over £5 million this season.

Commercial income

One area where the club did improve its revenues was commercially, enjoying a £400,000 (six per cent) increase on 2023. This was still down on 2017 and 2018, but notably outstripped the two years prior to then, both seasons in which Derby were in the Championship.

That’s a strong showing for League One, though Derby will doubtless see room for growth here. Both Ipswich and Sheffield Wednesday generated more commercially in the third tier, and £7 million would place Derby only around mid-table in the second tier. The expectation is that should grow this season. Derby’s sponsorship income was less than £2 million in 2023/24 yet had been £5 million in 2017/18, a result of playing in a higher division.

With the club back in the Championship this year, it will be interesting to see how successful the new ownership are in leveraging that status and the increased visibility it brings. FanHub, an app-based product that aims at rewarding match-going fans for loyalty to their club, was announced as the club’s new front-of-shirt sponsor this season, but no monetary figures have been publicly reported.

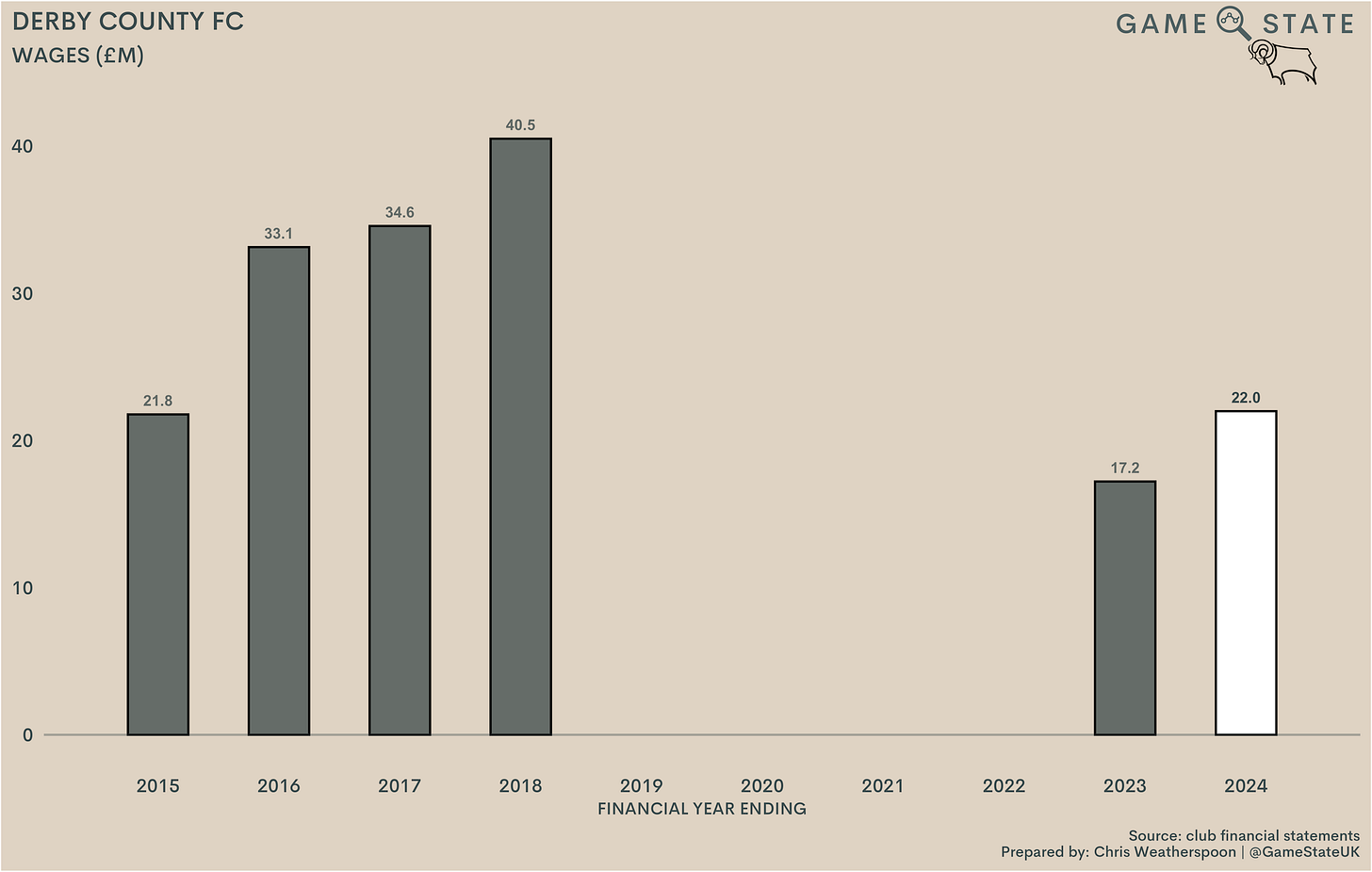

Wages

Derby’s wage bill increased to £22 million, up £5 million (28 per cent) from 2023. That was in part due to promotion bonuses, which comprised £1.2 million of the increase, though that still leaves an underlying rise of £3.6 million (21 per cent).

That 21 per cent underlying increase is a tad surprising, as Derby already paid out big wages for a third tier club. Non-playing staff increased by 20, whereas playing staff were only up by four from 2023, so perhaps a chunk of the monetary increase came from the former, but either way Derby now occupy a very small grouping of clubs in League One that have spent over £20 million on wages in a single season.

In fact, though accepting we’re missing 23 teams’ worth of data for last season, Derby’s wage bill was the highest in League One in the last five years, while their staff costs in 2022/23 had been the third-highest.

In terms of Derby’s ability to pay those wages out of day-to-day operating activity, the club’s wages to turnover jumped back above 100 per cent, hitting 113 per cent having been down at 84 per cent last year. That did include over £1 million in promotion bonuses, but even removing those still leaves the metric at a worrying 107 per cent. In other words, even without promotion, Derby would have spent more on wages last season than they recouped in income.

That’s quite obviously not a good thing, but it’s not especially surprising either. Derby, like most English clubs, don’t disclose the split of football wages (i.e. players and coaching staff) to non-football costs, but the size of the club means they’re never going to be paying at the bottom end of the third tier. Derby had 138 administrative staff in their employ in 2024, the fourth-highest among those clubs in League One who disclose staff numbers.

Even so, it’s also fairly clear the club didn’t shirk on wages in seeking promotion. That proved a successful endeavour, one Clowes and fans alike will no doubt view as money well spent, but it will be interesting to see where Derby’s wage bill sits this season. Based on most recent figures, their wages to revenue metric was the highest (i.e. worst) in the third tier, and would have remained so even with those promotion bonuses excluded.

It’s worth noting here that, for the second year running, reports soon after the release of Derby’s accounts have included a figure for the club’s player wages. These have generally first appeared in local media, so perhaps the club are briefing journalists on the specifics, but without any proof of that the reported figures bear the hallmarks of a misreading of one of the disclosures Derby have provided in the past two years.

That disclosure relates to the Salary Cost Management Protocol (SCMP) rules which apply to clubs in Leagues One and Two, through which the EFL limits the amounts clubs can spend on ‘player-related expenditure’ in a given season. That limit was 60 per cent of ‘relevant turnover’ for Derby last season, and the club accounts disclosed SCMP ‘headroom’ of 53 per cent, which is surely a misuse of the term; Derby’s player-related costs were significantly more than just seven percent of relevant income.

More likely is their SCMP ratio was 53 per cent, compared to 58 per cent a year ago. That seems odd at face value - how can their percentage have fallen when wages increased and revenue fell? - but the EFL’s definition of turnover for SCMP purposes includes, for example, player sale profits, which were up this year. As well, certain costs that fall into the club’s wage bill are excluded, including the costs incurred on players aged under 21.

In other words, drawing a straight line from the club’s SCMP figure to their playing wage bill is impossible. Clearly Derby had no issues with compliance, and the size of the club means that their non-playing wages will dwarf many clubs in League One, but it’s still clear they shelled out plenty in their successful pursuit of promotion.

Other expenses

As well as the wage bill increasing, Derby’s other expenses were up too, by £2 million (15 per cent). These costs are generally non-staff expenditure excluding depreciation on fixed assets, and clubs have seen rises across the board in the recent high-inflation environment. Yet this still marked a sizeable uplift for Derby, and while some of it will be attributable to Clowes and the management ensuring the club is sufficiently funded (the club’s Category One academy will cost a small fortune to run, for example), it’s still an area they’ll hope to arrest growth in.

Outside of Ipswich, Derby’s other expenses were more than anyone else’s in League One, and by quite some distance too. Of course, plenty of that will be attributable to the club’s well-regarded academy, which was a necessary source of talent during their financially troubled years. Per the academy’s standalone accounts, last filed in 2018, the facility cost in the region of £6.5 million then, and will only have risen since.

With big clubs come big costs, so it’s no surprise Derby are at the top of League One in this regard. Yet revenue is limited in the third tier and it’s clear why clubs with big grounds need to get up and out of the division as soon as possible. Derby’s other expenses comprised 73 per cent of income last season, a huge proportion, and ruinous over a long period of time. Thankfully, that figure will drop this season as income grows.

That wasn’t actually the highest other expenses to revenue metric in League One, with Charlton Athletic’s non-staff costs taking up more of the club’s income than was the case anywhere else. That should trouble Charlton fans; while Ipswich and Derby have each now been promoted, The Addicks remain in the third tier, and will need to find a way to fund costly daily operations on reduced revenues.

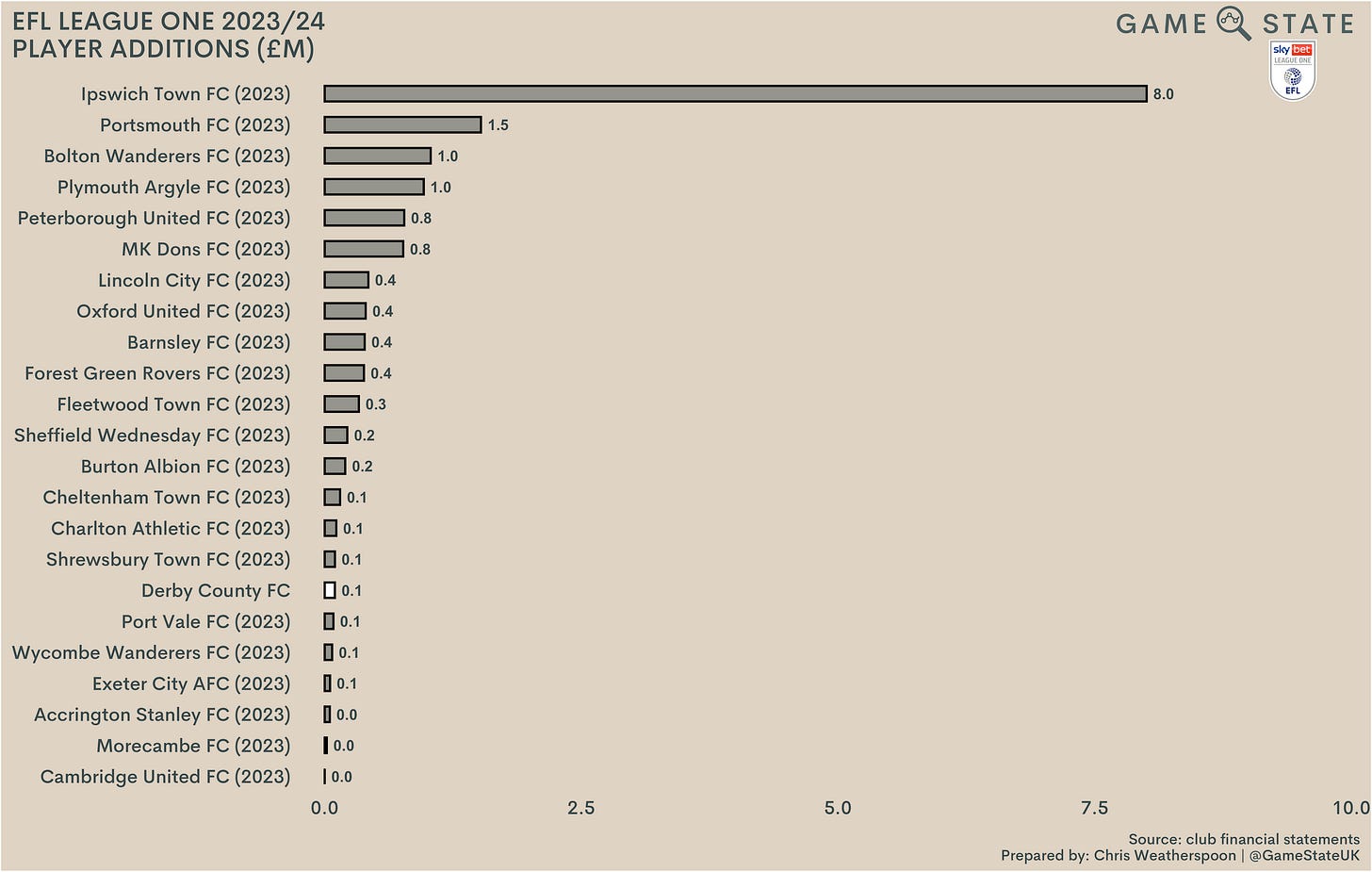

Player trading

For at least the second year running, Derby received more for selling players than they spent on new ones. That marks a fairly big departure from previously. In the five seasons to the end of 2018/19, The Rams had a net transfer spend of £52 million. That mightn’t seem much in the context of the huge sums we hear thrown about at the top level nowadays, but it did comprise roughly two-fifths of the club’s total revenue in that period - and we already know Derby were spending more that their total income on player wages alone, never mind having to add transfer fees on top.

(Note that while Derby’s 2018/19 accounts never saw the light of day, disclosures in the 2017/18 financials confirmed a number of figures around transfers conducted in the following season.)

Derby’s desire for promotion to the EPL under Morris was so great that they spent 116 per cent of turnover on transfers alone in 2016, racking up a £29 million net spend. If you’re wondering how they also managed to spend 147 per cent of turnover on wages that season and only book a £27 million operating loss, then it’s worth remembering that 2016 was the year the club changing its policy toward amortising player transfer fees, ostensibly to reduce the annual charge going through the accounts. For their troubles, they wound up in court with the EFL and hit with a £100,000 fine, as well as being asked to restate their accounts for the period 2016 to 2018.

Last season’s transfer spend was minimal, with Derby relying on loans and free transfers to build a promotion winning squad. The club spent barely anything despite bringing in 16 players, instead preferring to direct resources at the wage bill.

Hardly anyone spends money on transfer fees in League One, with Ipswich a pretty stark exception, though Birmingham City have blow even them out of the water with their activity in the current season. Derby’s spending focused on wages in their promotion year, and it’s easy to understand why.

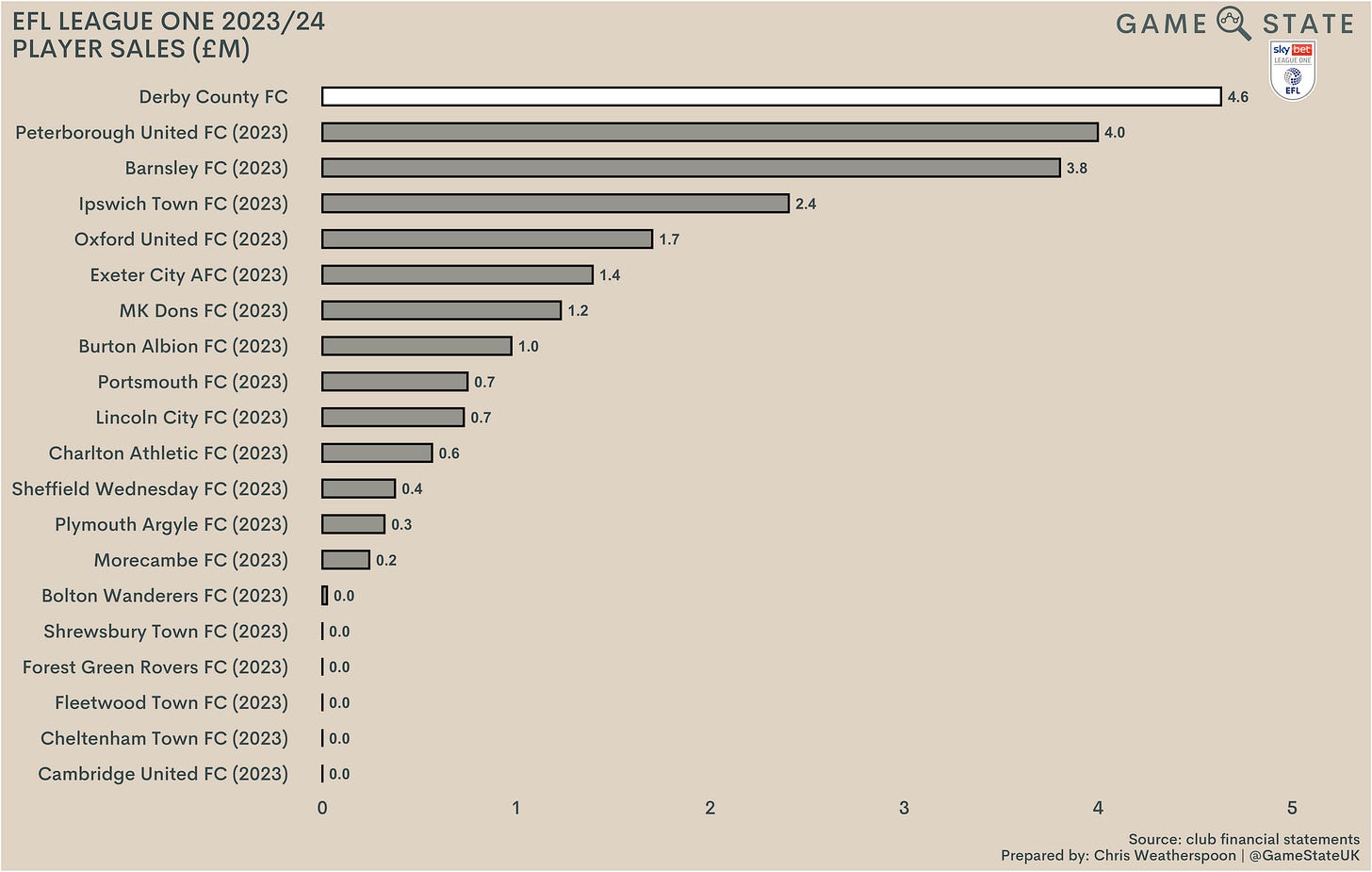

Where Derby did top the table was in player sales, recouping a little under £5 million on Knight, Bird and Krystian Bielek, as well as benefitting from sell-on clauses held for Omari Kellyman and Morgan Whittaker, among others. That was pretty necessary in helping reduce losses, and the fact they were able to sell some star players yet still gain promotion is undoubtedly positive.

The upshot of the club’s transfer activity was a significantly reduced player amortisation charge, with hardly any of the playing squad having been signed for a fee. That’s an even bigger drop on past figures than the below suggests; remember that the club manipulated its amortisation policy under Morris, and the ‘true’ amortisation charge, if the published accounts had been in line with accounting policy used at other clubs, would have been even higher still.

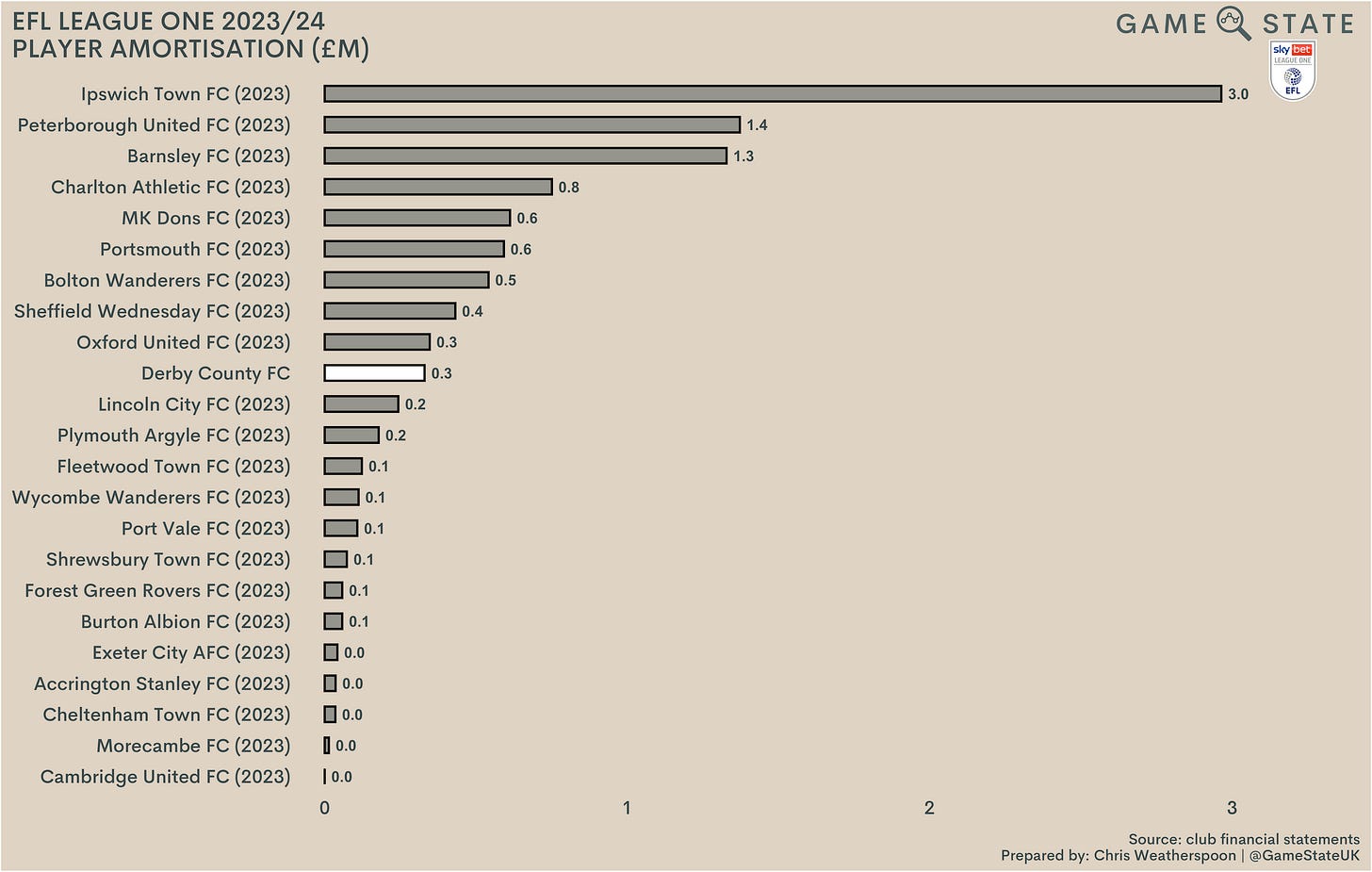

In line with low gross spend on transfers, amortisation charges are small in League One, though Ipswich again did their best to be the exception that proves the rule. Derby’s £0.3 million charge saw them just sneak into the top 10.

Derby’s profit on player sales just about tripled from a year earlier, up to £5 million and higher than all bar one of the seven seasons for which we have data from 2015 onwards.

As part of the disclosures in the 2018 accounts, the club confirmed it actually made a loss on player trading in 2018/19, which in part helps explain one of the reasons they lurched into financial difficulties: Derby invested heavily in the playing squad, failed to achieve promotion and didn’t have players that could bring in the sizeable profits needed to offset operating losses.

£5 million in player profits didn’t offset operating losses last season either, but it’s a pretty good figure from the third tier. Those profits derived from the sale of academy players, so pretty much all of the sale values went toward reducing the club’s annual loss.

Squad cost

Derby’s squad cost at the end of June was scarcely over £1 million, a far cry from just six years ago, when hefty transfer spending saw them accumulate a group of players at a total cost in excess of £60 million. Even over half a decade on, based on latest figures that would be the sixth most costly squad in the Championship.

Of course, the club’s largesse proved far from worth it and, even had they not tumbled into administration, they’d already acknowledged their failings in squad-building. In the decision document from one of several legal tussles with the EFL a few years ago, it was confirmed that the club’s never-published 2018/19 accounts included a proposed impairment charge of £22 million. In effect, Derby accepted that the book value of the squad bore no resemblance to what they might feasibly sell players for.

By contrast, Derby’s squad wasn’t even in League One’s top 10 most expensive. Ipswich Town’s hefty spending had them way out in front, but there were still another nine clubs ahead of Derby by this metric, reflecting the belt-tightening that has been necessary at Pride Park. That said, wages remain both a club’s biggest cost and a better barometer than transfer fees or how the team will actually perform on the field and, as we’ve already seen, it’s clear Derby focused their spending there instead.

Balance sheet

Football debt

Already spotty financial data is even more so when it comes to Derby’s transfer receivables and payables, as the club didn’t start disclosing such amounts until 2017. In any case, through reporting during and before the administration process, we already know the club’s transfer debts (i.e. amounts owed to others for players bought by Derby) drooped even deeper into the red than the £11 million of 2018, so the net £3 million the club was owed by other clubs at the end of June 2024 marked a welcome change.

Very few clubs in the third tier disclose transfer debts and receivables, so there’s little use in drawing comparisons here, but that Derby are in a net positive position means they’re in a freer state to utilise existing cash reserves than they have been for some time.

Financial debt

Debt is often held up as a sign of a club in trouble, but that doesn’t really track in Derby’s case. While we’re obviously missing a lot of data from Mel Morris’ time in charge, the reality is that Derby weren’t overly indebted from much of his reign; money went in as shares, and it was only when Morris’ own ability to keep up with the commitments he’d imposed on the club began to wane that the club ran into trouble.

A look at the club’s debts from then to now would suggest trouble: at the end of June Derby owed £48 million. Yet that was owed entirely to Clowes’ company, attracted no interest and, as confirmed by the accounts, will be, at least in part, converted to equity in the near future.

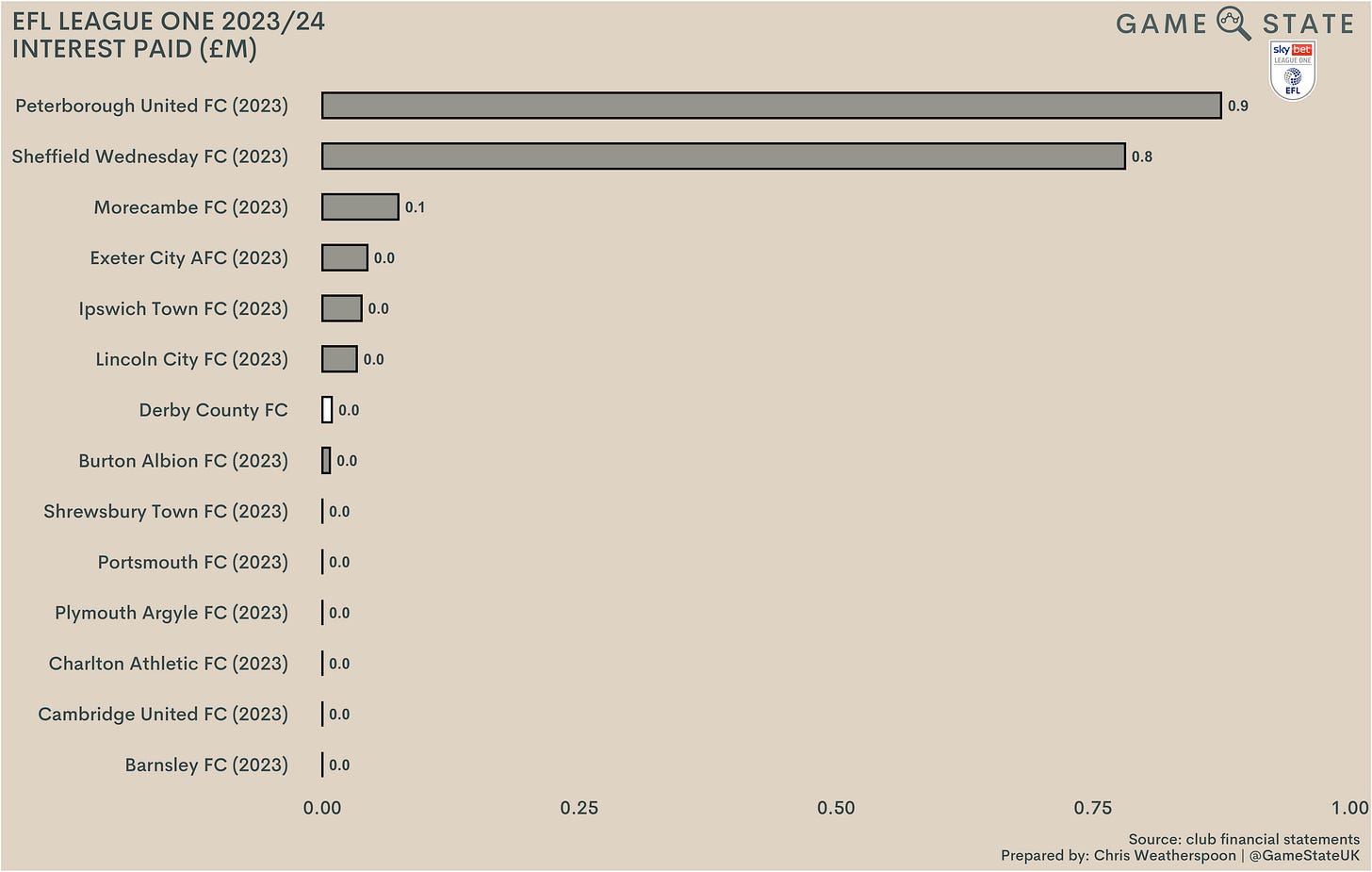

Derby’s debt was one of League One’s highest, and might cause the casual observer some alarm given the club’s recent financial troubles. Yet the debt incurs no interest and will reduce once any equity conversion takes place. Debts at League One clubs are starting to pile up but, again, they incur little to no interest, so don’t hamper club operations.

Indeed, based on most recent figures, no League One side paid out over £1 million in interest on their debts. That might not be 100 per cent true - several clubs don’t publish cash flow statements, so it’s difficult to know exactly who is paying what - but the underlying point is that most clubs in England’s third tier are the beneficiaries of owners who fund continued losses without charging interest, in part because there’s no money left over to pay that interest anyway.

Cash flow

Cash is king and never more so than at Derby in recent years. Like many businesses, their woes came when the ability to pay their bills in a timely fashion diminished and, as has been the case often with football clubs in trouble, it was to the taxman that Derby and Morris opted to let payments lapse. By the time the club entered administration, HMRC were owed £29 million.

Part of the reason for that was the club’s overstretching meant it was haemorrhaging cash, with a staggering £82 million lost from operating activities in 2018. Little wonder Morris moved to inject £81 million into club coffers with that Pride Park purchase.

Cash operating losses haven’t disappeared yet either, a fact of life for a big club in the third tier. Last season Derby lost £15 million in cash on operating activities, with the bulk of that paid for via a £12 million cash injection from Clowes.

Once again, Derby trailed only Ipswich when it came to losses, and once again the gulf to the remainder of the division wasn’t small. Few of the clubs who published cash flow statements were cash-positive from operations, reflecting the profitability difficulties nearly all clubs now experience.

Derby’s 10-year cash flow statement is impossible to piece together given the four-year gap in published accounts, but across the six years for which we do have figures we can determine the club received £229 million in funding, split £114 million in shares issued, £81 million from the sale of Pride Park and a further £34 million in net loan funding. In reality, the funding the club has received since 2015 is a fair sight higher. In any case, that £229 million went on:

£176 million covering operating losses;

£33 million net transfer spending;

£17 million capital expenditure on infrastructure;

£2 million movement in cash balance across the missing four years; and

£1 million on interest payments.

One criticism that can’t really be thrown at old owner Morris was the idea that he skimped on facilities. On the contrary, Pride Park and the club’s academy remained in good upkeep, and it’s rumoured that the (many) prospective buyers of the club were frequently impressed with what they found. Despite sinking deeper and deeper into the red, Derby routinely spent more on capital projects than other Championship clubs.

Those sums have necessarily dropped off in the last two years, and it’s probable the club won’t see any dramatic spend on capex until they’re on more solid footing in the second tier. In a way that’s just fine, as one of the few green ticks against Morris’ name was his refusal to let the club grow shabby.

Derby’s £1 million capex in 2024 wasn’t anywhere near the top of League One, though it’s worth noting that clubs at this level see fairly large fluctuations from year to year. In most cases, big single-year spends on infrastructure amount to specific projects being undertaken rather than a recurrent large cost.

Owner funding

Derby were in dire straits before Clowes arrived on the scene, and it’s to him they owe their continued existence. The hope is likely that the club will become broadly self-sufficient, but such was the damage inflicted under Morris that it still seems some way off.

Clowes put in a further £12 million in loan funding last season, taking his total commitment to date to £70 million. That’s a lot, especially for a League One club, but it needs to be weighed in the context of the situation.

Clowes not only had to fund a club whose infrastructure is too vast for England’s third tier, he also had to buy Derby in the first place (£13 million), then wrestle Pride Park from Morris’ grasp (£22 million). £19 million worth of creditors needed to be paid immediately to avoid the club incurring even further points deductions upon leaving administration, and a further £16 million has gone into the club since to fund operations.

Derby’s near-death experience certainly didn’t arise because of a lack of owner spending. On the contrary, Morris was like the proverbial kid in a candy shop (and yes, the fact he made his fortune from the Candy Crush Saga video game might now make a lot more sense), splurging at will with little apparent fear that the money would dry up.

In his first four and a half years at the helm, Morris injected £212 million, either in the form of shares of that £81 million ‘purchase’ of Pride Park. The true extent of his funding was even higher; at the time of the club entering administration in September 2021, Gellow Newco 203 Limited, then the club’s parent entity, was owed over £120 million.

Derby’s reliance on owners has continued even after Morris’ departure, though that was fairly inevitable. Ignoring amounts paid for the club and Pride Park, as those didn’t go directly toward funding club operations, Clowes has already committed over £35 million in operational funding to the Rams (albeit over half of that went toward debts incurred before his arrival).

The club’s ground does remain under the auspices of that Gellaw Newco 202 Limited (confused yet?) entity Morris set up and bought it from the club with, and whether there are plans to officially return it to the football club are unknown. At present the club’s operating lease on the ground costs around £1 million per year, which increases losses but is unlikely to be actually paid. Whether those payments will be waived in the future is not yet known.

Derby have received £35 million in owner funding in just the last two seasons alone, a big sum for the third tier, but one that on its own doesn’t take into account what came before. The Rams’ debt to Clowes is actually larger, but that includes the £13 million cost of buying the club out of administration, and would be even higher if the £22 million cost of buying Pride Park were included.

Ordinarily we’d look at owner funding over a number of years, but the patchy record of Derby’s accounts and the fact they’re the only League One club to publish 2024 financials yet makes that a bit of a silly exercise. Regardless, it’s pretty clear that Clowes’ commitment to the club has been big already, as only Ipswich received more in owner funding in a single year in the third tier, at least based on most recent figures.

Profit and Sustainability Rules (PSR)

Domestic

As mentioned, Derby’s accounts include reference to SCMP, the financial regulations that apply to League One and League Two clubs. In short, third tier clubs can spend 60 per cent of ‘relevant turnover’ on ‘player-related expenditure’. Per Derby’s accounts, the club’s SCMP ratio was 53 per cent in 2023/24, seven per cent below the limit.

SCMP doesn’t apply in the Championship, with clubs instead having to comply with loss limits. There’s a perception in some quarters that clubs coming up from League One start anew - i.e. only financial results in their years in the Championship are considered - but that’s not the case.

Instead, club losses are assessed over a three-year period, including any years spent in League One. To that end, Derby might have cause for initial concern; in the last two years alone they’re posted pre-tax losses (exclusive of that goodwill impairment, which the club has confirmed with the EFL is allowed to be excluded from their calculation) of £25 million. Championship clubs are allowed losses of £39 million over three years, but only if owners provide ‘secure funding’, generally in the form of share capital.

That hasn’t happened yet, so on face value Derby are sitting £10 million above the £15 million losses they’re currently allowed over the last three years, without considering the finances of the 2024/25 season. Yet that ignores any other deductions the club can make, like the cost of running their Category One academy. That was pegged at over £6 million as far back as 2018 and, while the likelihood is this has increased since, even a conservative estimate of those costs remaining steady would ensure The Rams need worry little about PSR compliance this season.

Game State’s model estimates that Derby could lose £18 million in 2024/25 without breaching the EFL’s profit and sustainability rules. That’s without including any secure funding that may arise from Clowes converting loans or injecting fresh equity this season; the amount The Rams can lose could increase by up to £24 million dependent on activity in that regard.

There is likely an element of strategy in play around Derby’s current funding and its nature. While that near-£50 million of debt might set a few hearts racing, it could make sense to delay conversion until the point whereby the club actually needs help complying with financial rules. Whatever the case, it seems unlikely they’ll be tackling the EFL in court again any time soon, which will likely be music to the ears of both parties.

The future

Back in the second tier, Derby’s return to the Championship has been middling, though after the turmoil of recent years that probably suits their fans just fine. At the time of writing they sit 15th in the table, though have only won five of their first 18 league games. How their season transpires might rest on the busy Christmas period, over which The Rams will face clubs in receipt of parachute payments (and thus far greater resources than them) - Leeds United, Burnley and Luton Town - four times in six games.

Sunday’s 1-2 loss at home to Sheffield Wednesday will have hurt, especially as The Rams didn’t fall behind until the fourth minute of injury time, but it was the fourth game running where Derby enjoyed the better of the chances. That they won none of those games is hardly encouraging, but it does point to the possibility that they’ll soon see their luck turn.

Derby County’s finances are a world away from where they were a few short years ago - mercifully so. The club is by no means ‘fixed’ just yet; there is work to do in improving income streams and using player trading as a more reliable source of profit, but the progress made since Clowes took ownership two years ago is both tangible and welcome.

Sceptics might highlight that there were initially few signs Mel Morris would ever run out of money to meet the liabilities he’d wracked up, and though little in life is certain there are at least a few outward signs that the club’s future is currently a fair way safer under Clowes.

Clowes Developments (UK) Limited, the family-run property company through which the club was bought, published their own 2024 accounts last week, recording £10 million in pre-tax profits and positive operating cash flows. Those results include the losses incurred by Derby; in other words, the wider Clowes business can, at least currently, underwrite the losses of the football club.

How long Clowes’ ownership will last remains to be seen. He was in many ways a reluctant buyer, only really stepping in as Derby approached death’s door at quickening pace. As recently as September, it was reported he was looking into the possibility of selling a majority stake in the club, surmising new investors would be required to push the club to the next level.

If he does take his leave any time soon, what happens to the debt and Pride Park will be of paramount importance. There is little sign to date that Clowes would do anything other than right by the club. If that continues, he’ll doubtless be regarded as a Derby County hero for quite some time.