A new TV deal for the EFL - is it worth it?

Ahead of the return of the EFL this weekend, Game State looks at the richest TV deal in the organisation's history - and what it cost the league and its clubs to obtain it.

The announcement was jubilant, the adjectives unequivocal. A ‘landmark’ deal; a ‘record’ agreement; ‘significantly enhanced’ exposure for the clubs of the English Football League (EFL). When the EFL and Sky Sports told the world of their newly inked deal back in May 2023, the headlines were clear: this was big news for the EFL and its clubs, and would heighten the profile of both.

Spanning five seasons from 2024 to 2029, the EFL agreed to sell Sky Sports its domestic live broadcast rights in a deal totalling £935 million, being £895 million in cash plus a further £40 million in ‘marketing investment’ from the broadcaster. In cash terms that equalled £179 million per season, a £60 million and 50 per cent uplift on the deal in place between the same parties for the period 2019 to 2024.

In choosing Sky Sports to be its broadcast partner for the seventh consecutive set of rights, a period stretching back to 2002, the EFL turned away a bid from streaming platform DAZN. The nascent company, seeking a foothold in English football, had offered an undisclosed amount to stream every EFL game for the next five seasons. In rejecting DAZN, the league ensured Article 48 of the UEFA statutes, more widely known as the ‘3pm blackout’ rule - whereby no football games can be broadcast in England between 2.45pm and 5.15pm on a Saturday - would remain in place.

Per the EFL’s own research, removal of the blackout rule could have led to a fall in attendance revenues of £37 million across the three divisions. To that end we can surmise DAZN’s offer probably came in at under £216 million per season - being Sky’s £179 million cash offer plus the above lost revenue - and definitely below £224 million per season, a figure which factors in the extra £8m per annum in ‘marketing investment’ that Sky’s deal includes. For their part, the EFL had originally targeted £200 million per season for the next five years.

The deal

Despite coming in below that target, the EFL’s new TV deal is, by some distance, the largest in its history. Only twice before has the league inked a rights deal that would return a nine-figure sum each year, and one of those was the ill-fated ITV Digital deal that collapsed after a single season in the early 2000s.

Unlike the behemoth that is the English Premier League (EPL), the EFL has not seen huge growth in broadcast revenues. That ITV Digital collapse saw the EFL turn back to Sky in 2002; the desperation of the situation meant the broadcaster bagged the rights for a lower annual fee than they had paid for their previous deal. Ten years later, Sky agreed another reduced deal, albeit only after a 2009-12 package that represented a doubling of the preceding agreement.

Based on the expected apportionment of monies across the three divisions (something we’ll consider in greater depth later in this piece), Game State projects the value of the £179 million per year to be split as follows:

EFL Championship: £133 million

EFL League One: £27m

EFL League Two: £19m

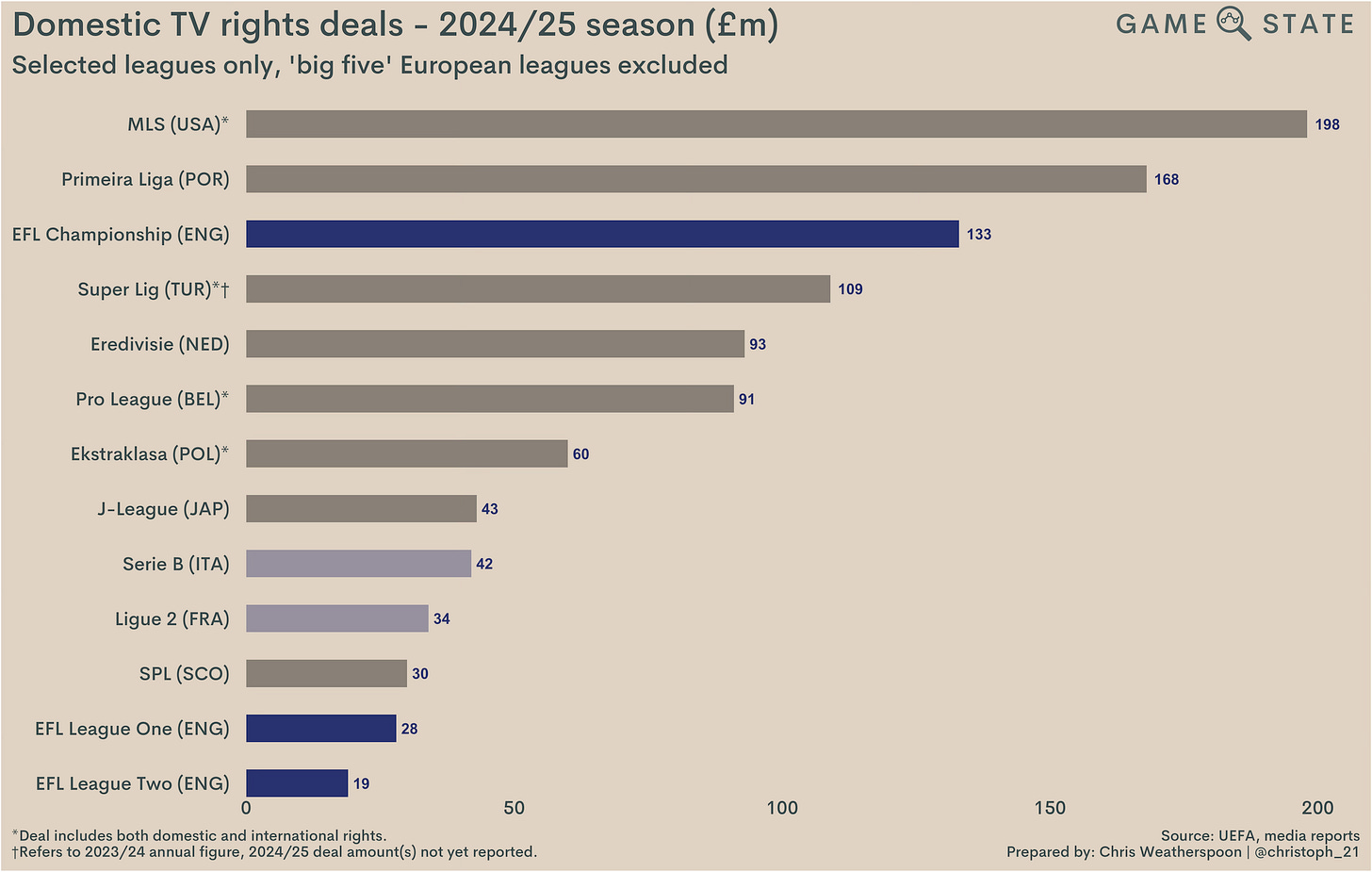

Those figures in isolation don’t mean a lot, so it’s worth comparing alongside rights deals secured by other leagues. The EFL’s domestic broadcast revenue pales in comparison to the sums enjoyed by Europe’s ‘big five’ divisions, where annual agreements this coming season range from £1.6 billion in the EPL to £443 million in France’s Ligue 1.

Yet outside of those leagues the EFL shapes up pretty well. The list below is non-exhaustive, but based on our projected split the Championship boasts by some way the highest TV deal in second tier football. Indeed, it shapes up favourably against many countries’ top divisions: £133 million per year is higher than the rights deals currently in place in Turkey, the Netherlands, Belgium, Poland and Japan.

Data on third and fourth tier rights deals outside of England is spotty, not least because the pyramid on these shores extends further than it does in many countries in continental Europe. Yet comparing the projected split of monies filtering down Leagues One and Two holds up favourably too.

League One’s £28 million isn’t a vast distance from the roughly £34 million secured by Ligue 2 in France for the coming rights period. More starkly, England’s third tier TV deal is just a smidge behind the £30 million per year deal currently in place for the Scottish Premiership (SPL), a fact that is both cause for celebration in England and one for consternation north of the border (though it's worth highlighting the SPL contains half as many teams as League One, so its clubs will receive more on an individual basis).

The games

Of course, in order to secure a relatively high sum for its broadcast rights, the EFL had to give something in return. That came in the form of huge uptick in the number of games Sky Sports will broadcast live across the next five years. Starting this evening with kick-off in the Championship, Sky will broadcast a whopping 1,059 EFL games both in this season and the following four, 56 per cent of the EFL’s total annual games.

Those 1,059 games are split across the following competitions:

328 EFL Championship matches (59 per cent of all games in the division)

248 EFL League One matches (45 per cent)

248 EFL League Two matches (45 per cent)

15 play-off matches, being five per division (100 per cent)

93 Carabao Cup matches (100 per cent)

127 EFL Trophy matches (100 per cent)

That quantum of live matches represents a sevenfold increase on the number of games shown across the 2019-24 rights period and will be, by a long way, the most screened of any English football competitions in history. So many games are due to be broadcast that Sky have set up a new standalone channel, Sky Sports +, to facilitate them all.

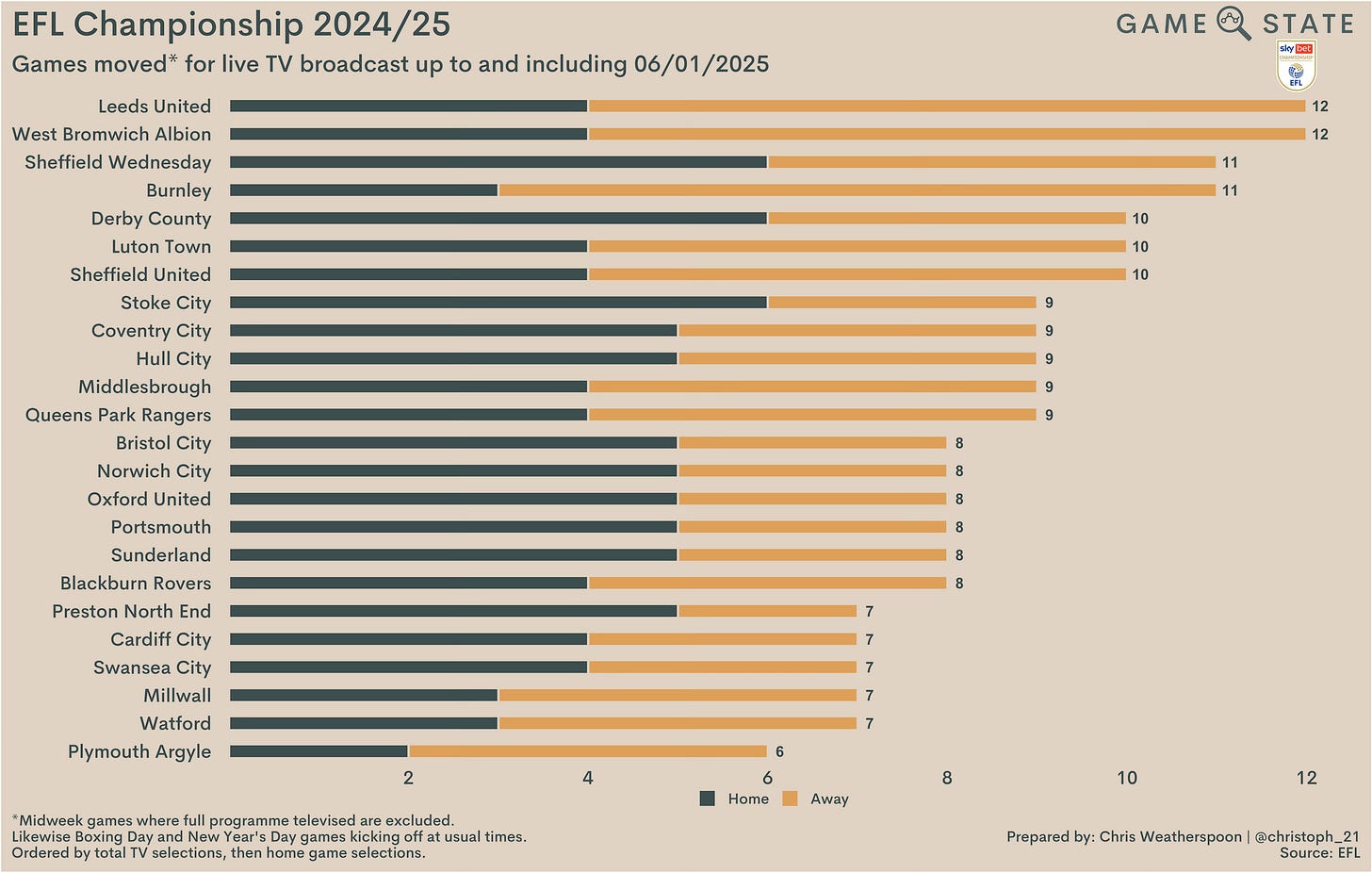

Inevitably, that means EFL clubs will be gracing television screens far more frequently than they have in the past. The league has already announced all televised fixtures up to and including 6 January 2025, a new initiative aimed at aiding the planning of match-going fans, meaning we already know how many times each of the 72 clubs will be shown between now and FA Cup third round weekend.

The results are striking. Taking the Championship as an example, 26 rounds of televised fixtures have been announced, and all 24 teams will have at least half of their matches screened live. The EFL has already announced that, on average, Championship clubs will be televised 23 times per season; for some, it’s already clear they’ll zoom well past that figure.

Both Sheffield Wednesday and Leeds United will be shown on Sky 18 times by the beginning of January, near enough 70 per cent of their matches in that time. In years gone by, the most-screened Championship club in a full season generally topped out around the 20 mark. In several cases, clubs were televised just the agreed minimum of four times across the year.

With a huge increase in televised games and no removal of the 3pm blackout rule, the immediate concern of many fans, particularly those who own season tickets, will be understanding how their matchday routine will be impacted. In a few cases, it won’t be. All midweek games will now be televised, as will every game on the upcoming opening weekend as well as Boxing Day and New Years’ Day. The final weekend of the season is almost certain to be fully televised too.

But what does our table look like if we only consider matches where kick-off times have been moved to accommodate live broadcast?

Here again, Leeds top the table with 12 games moved for TV, joined now by West Bromwich Albion. They each have eight away games on Sky between now and January, something which will doubtless make life more difficult for travelling supporters.

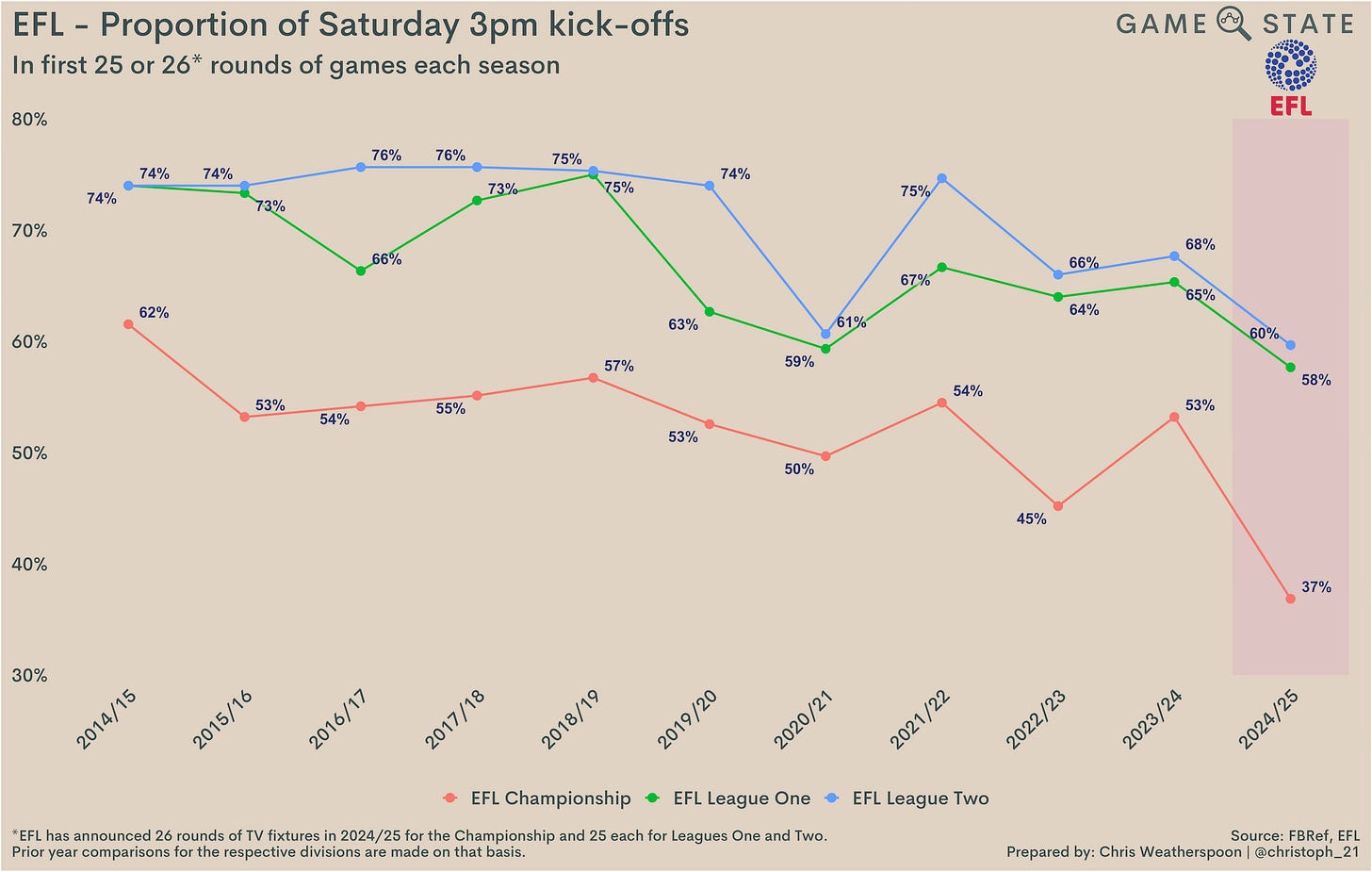

While those clubs are most affected, match-going fans across the board will see their schedules more disrupted than ever before. Up to the first weekend of January 2025, just 115 out of 312 EFL Championship games (37 per cent) will kick off at 3pm on a Saturday. Compared with the first 26 rounds of games in previous Championship seasons, that’s the lowest tally in the last decade, and almost certainly ever.

It is not a small drop either. 115 games is an 18 per cent reduction on the previous low of 140 seen in 2022/23, a figure that was deflated in part due to the curious timing of the 2022 World Cup, meaning more midweek fixtures were bundled into the opening half of the season than usual.

The number of Saturday 3pm kick-offs across the first 26 rounds of Championship matches has hovered at around 160 across the last decade, but was at 192 as recently as the 2014/15 season. The coming season represents a 40 per cent fall from then.

The most precipitous drop in Saturday afternoon kick-offs is in the Championship, but the retention of the blackout rule means Leagues One and Two are inevitably affected too. In both divisions, around 40 per cent of games up to the first weekend in January won’t kick off at mid-afternoon on a Saturday.

In the coming season, on average, of the 46 games played in the top four tiers of English football on any given weekend, just 22 will kick off at 3pm on a Saturday. While many have commended the retention of Article 48 in England, the rule itself is being rendered increasingly redundant by the mass movement of fixtures to other days and times.

How much this will impact clubs - for better or worse - is difficult to judge at this point. For the EFL’s part, they highlight that the true number of games broadcast across their competitions in a given season was already over the 600 mark, citing usage of the domestic iFollow service that has now been scrapped in the wake of this new deal (the international service will remain). To that end they contend the uptick in live games is not so large as it first seems.

More convincingly, the league highlights that attendances have continued to grow even as more matches have come to be shown on television. It’s their contention that match-goers will still remain so, stating their belief that “the balance we have struck grows media income but not at the expense of attendance income.”

The money

Money is, of course, the primary driver behind this new deal. As we’ve seen, the rights sale stacks up favourably alongside other leagues, albeit with the caveat that the EFL is giving up far more of its games in exchange.

How much they’ve given up becomes clear when we assess the deal on a revenue per game basis (i.e. the annual value of the deal divided by the number of games to be screened). Doing so results in a price per televised EFL game this season of just £169,000, the lowest amount since the early 1990s and a big fall from the peak of £1.2 million in the 2009-12 rights cycle.

How much clubs will care about that is up for debate. If the EFL’s expectation that matchday income won’t be depressed rings true, clubs will be less bothered about selling so much for so little (at least when it comes to this metric).

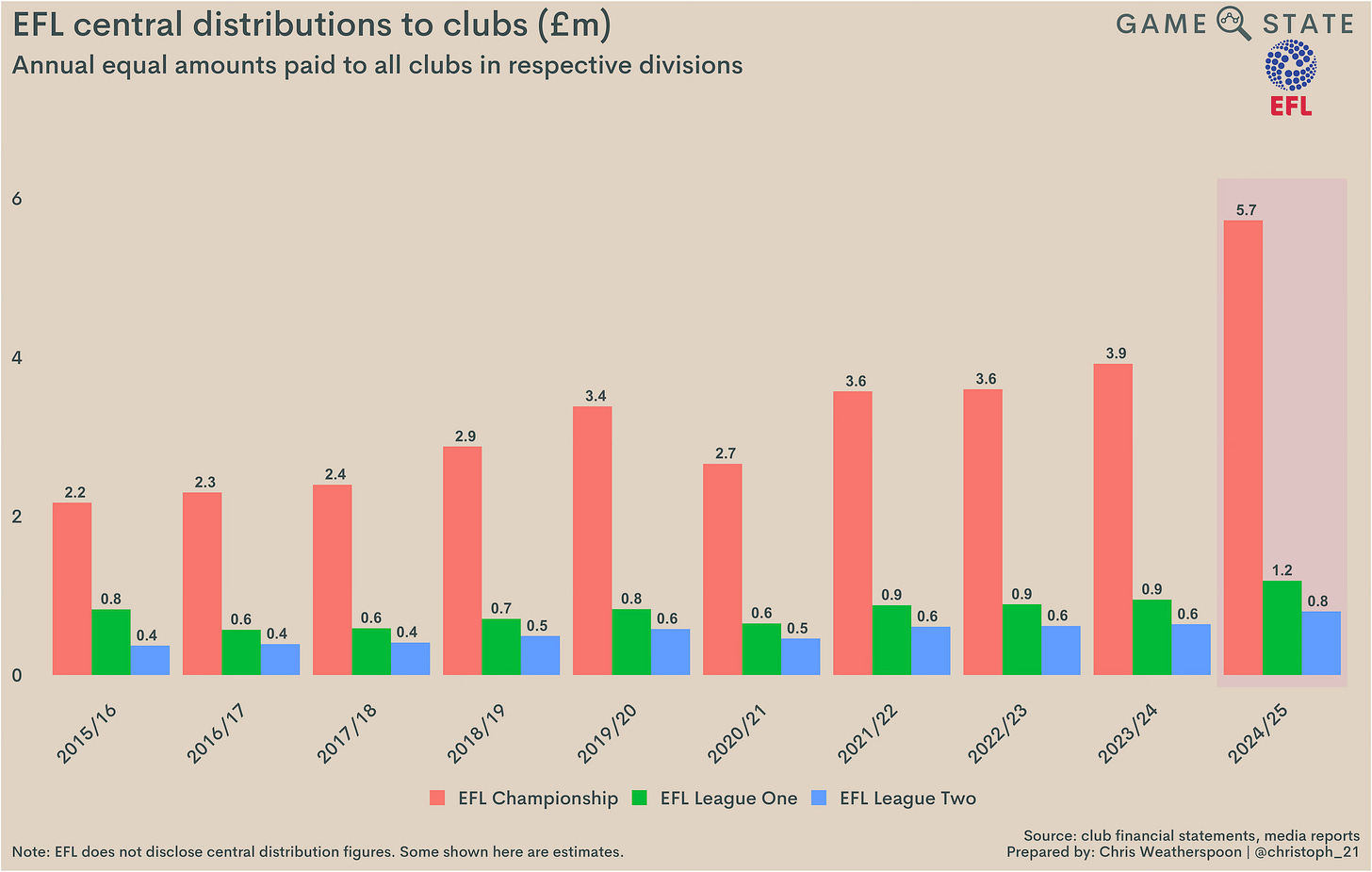

What they’ll be far more interested in is how much actual cash they’ll see from the deal. The calculation of the EFL’s distributions to clubs is a tad convoluted, not least because the “uplifted element” of the broadcast deal is distributed more favourably to Championship clubs than previous monies (a divisional split of 80/12/8 against last season’s 70/18/12), but the league has provided indicative figures already.

Per their announcement, Championship clubs can expect a 46 per cent uptick in central distributions from the league, while Leagues One and Two will enjoy 25 per cent growth. That means the estimated seasonal income from the EFL for clubs will be as follows:

EFL Championship: £5.7 million per club per season

EFL League One: £1.2 million

EFL League Two: £0.8 million

In the grand scheme of football finance, those figures are hardly jaw-dropping. Yet they do represent a real increase at the club level. In the case of Championship clubs, for probably the first time, distributions from the EFL are set to surpass the solidarity payments handed down from the EPL. The latter sat at £5.2 million in 2023/24 and, with negotiations over a revised agreement between the leagues stuck firmly in the mud, it seems likely that in 2024/25 the EFL will finally distribute more to its own clubs than its bigger brother will.

That says more about the attitude (or perhaps greed?) of EPL clubs than anything else, but EFL clubs will still welcome the income boost. In 2022/23, clubs across the three EFL divisions posted collective pre-tax losses of £428 million and, while this deal will clearly come nowhere close to wiping those out, it could help bring them down.

Based on the estimated distributions to clubs, and assuming all else remained equal, the money earned from new TV deal would have reduced losses in the Championship by 14 per cent, those in League Two by 10 per cent and those in League One by six per cent.

Unfortunately, all else tends not to remain equal. As Game State has detailed elsewhere recently, wages in football, by far a club’s biggest cost, have kept increasing regardless of whether incomes have done the same. If the uplifted broadcast revenue clubs receive from the new deal simply filters straight into the pockets of players (and their agents), then those losses detailed above won’t budge.

There have been shifts toward choking off wage growth, not least in UEFA’s introduction of squad cost controls, a measure EPL clubs will be adopting in the near future too. To that end, it’s worth considering how much of a dent the uplifted income would make in club wage bills, using most recent figures as a test dummy.

For the most part, the increased income for clubs comprises less than 10 per cent of their most recent wage bills (note: several League One and League Two clubs do not disclose their staff costs). The two exceptions, Rotherham United and Blackpool, are both clubs that sit at the bottom of the wage table in the Championship and, tellingly, have each been relegated in the last two seasons.

From a revenue perspective, increased broadcast income will naturally impact clubs differently. For recently relegated clubs, an extra £1.8 million from the EFL will pale in comparison to the near-£50 million parachute payment they currently stand to receive from the EPL. For those clubs who have lingered outside the top tier for years, the income will be far more impactful, particularly in the Championship: the uplift in TV money comprises more than 10 per cent of 2022/23 revenues for five different clubs.

Returning to losses does however make it clear that more will need to be done if clubs are to tangibly improve their finances in the long run. Of the 70 EFL clubs to have published financials for the 2022/23 season, 62 posted a loss. If we add in the uplift promised by this new deal in line with the divisions clubs were in that year, of those 62 only three - Blackpool, Rotherham United and Burton Albion - would see the new income convert their loss into a (small) profit. In other words: this new TV deal alone will fall a long way short of pushing the pyramid into profitability.

That is not to say it is worthless. The financial benefits or consequences of the new deal can’t be measured just by assessing the uplift in broadcast rights in isolation. The EFL appears confident that attendances, and therefore matchday income, can continue to grow even as more games appear on our televisions.

Another area where EFL clubs should seek to benefit is in the value of the commercial deals they ink over the next five years. While viewing figures remain to be seen, the heightened exposure afforded to clubs will correspondingly increase the number of eyes on, for example, front-of-shirt sponsors.

Savvy clubs will estimate and keep data on audience impressions, knowing the ability to show a tangible increase will push up the price they can request from sponsors. It has been rumoured that music streaming giant Spotify would have paid more to FC Barcelona for their front-of-shirt deal had the Spanish giants been able to provide more robust data around audience numbers.

The EFL’s new TV deal will bring a welcome increase in revenue for clubs, but it is far from a panacea. Even if the entirety of the new income was used to plug gaps, an overwhelming majority of clubs would remain loss-making; in the Championship, based on latest figures, clubs would still have lost an average of £11 million each in 2022/23. More will need to be done in that respect, principally a reduction in player wages. The league seems adamant the new deal will provide sufficient financial upside to make it worthwhile, but it remains to be seen whether the uprooting of a huge number of games from their usual time slots will see match-going fans grow weary.

To further that point, the new deal could also open a schism between fan and club. Clubs may well benefit financially, but it’s hard not to wonder if it will come at the cost of stirring disillusion among supporters. A plethora of Saturday lunchtime kick-offs will go against the habits of a lifetime for many, moving EFL watchers into line with what fans of EPL clubs have had to get used to in recent years.

The obvious difference between the two is that EPL clubs get a lot more money in return, and their fans get to watch a higher standard of football. The impact of the EFL’s new TV deal will be felt immediately. Whether it’s deemed to be a good thing overall will take longer to unravel.